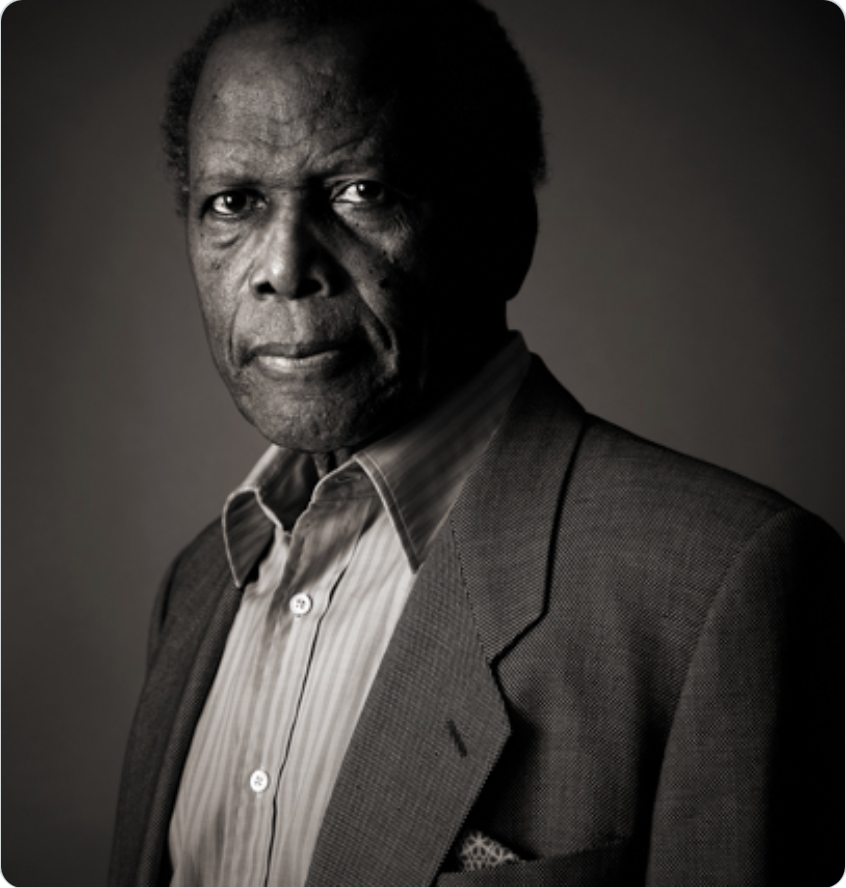

Letter from the Editor

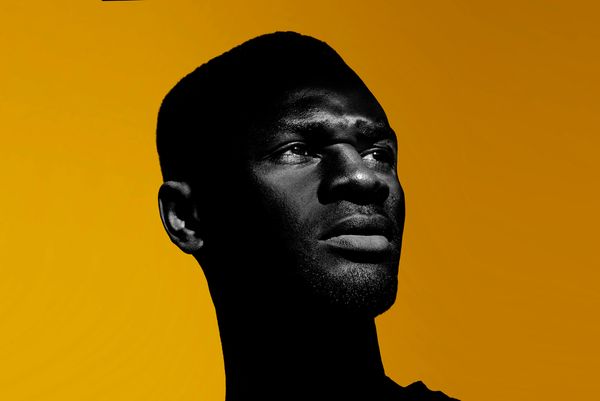

To Sir, With Love

My earliest exposures to the late Sidney Poitier were television broadcasts of Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, In the Heat of the Night, and To Sir, with Love. While I didn’t know him personally, Mr. Poitier seemed very familiar to me. For a Black man to be “articulate,” charming, hold an unwavering positive self-image, and whose comportment commanded respect was neither new nor out of the ordinary to me. My father and his peers embodied those same qualities. But the portrayal of men like my father on TV and in films? That was another matter altogether.

I didn’t discover Mr. Poitier’s autobiography, The Measure of a Man, until I was in my mid-forties. In it, the Oscar-winner surveys his life to assess whether he’s lived up to the standards he has set for himself. It’s a magnificent read. Of course, he recounts the backstory of his film career, but he also shares the highs, lows, questioning moments, and triumphs of his life. If you have a reading list, add this one to the mix, but wedge it near the top. And if you don’t have a reading list, the book will mark the beginning of a rewarding habit.

In The Measure of a Man, Mr. Poitier writes about his teenage years away from his home on Cat Island, Bahamas, and his first encounters with racism in South Florida. Florida. Geez, even to this day, the state judges its Black men against misconceptions of who it thinks we are, the scope of our abilities, even the validity of our humanity. But Mr. Poitier also tells of his saving grace: the irrepressible sense of self-worth and right and wrong instilled in him by his parents.

While reading Mr. Poitier’s autobiography parallels in my own life sprang to mind. As a Black boy with dwarfism, my parents also instilled the importance of knowing the difference between right and wrong and a strong sense of self-awareness and my own giftedness. And as a native Floridian, the tendency for those who did not know me to view my potential as less than their own only served to inspire me to demonstrate all that a Black boy—and later, a Black man—was capable of.

It’s common for people to wonder why people can be so affected by the passing of people they've never met. I can only speak for myself and say that in the case of Mr. Poitier, it’s a matter of identifying with similar circumstances and affinities. His ability to push through very real and almost palpable barriers inspires me. His life is a bittersweet testament to how far Black people have come and points to the areas America has course-corrected to align itself with the right side of history. But at the same time, his life mirrors the issues left unresolved and how much further we have to go.

I hope you’ll take the time to read A Measure of a Man. Mr. Poitier’s story in his own words will not disappoint. And I hope you’ll enjoy this week’s “OHF Family Tree” installment in which OHF writer Glenn Rocess tells of his journey out of the abject racist belief system of the Mississippi Delta.

Love one another.

Clay Rivers

OHF Weekly, Editor-in-Chief

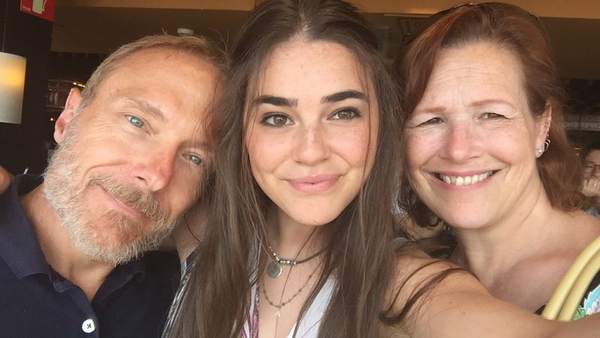

OHF Family Tree Interview: Glenn Rocess

Glenn Rocess’s journey out of his racist upbringing in the Mississippi Delta

OHF Weekly In four sentences, how would you tell us you’re on Team Racial Equity without saying you’re on Team Racial Equity?

Glenn Rocess It wasn’t until I was in my thirties that I began to realize that I was raised racist, that the entirety of my birth family was racist, and that every one of us had been part and parcel of the racism that defines the Mississippi Delta to this day. Even more troubling was the realization that none of us recognized our racism for what it was, and that all of us were on the wrong sides of history, morality, and honor. I cannot change the few distant relatives who remain, but I can use the blessings I’ve been given to help right the wrongs we all had committed and perpetuated.

OHF Weekly What was the moment you decided to write and publish your works for the world to read?

Glenn It’s hard to know which straw is the one that broke the camel’s back, for that straw is insufficient without the load of other straws the camel had already been bearing. But if there is one moment that stands out, it’s a short encounter with a stranger in Subic Bay in the Philippines. I was sitting at a table in an outdoor bar while on liberty (“off duty” is perhaps the better term for those unfamiliar with Navy terms), and I was doing what I enjoyed most: having a cold beer while writing about what I had experienced.

There were local women in the bar—one could call them “bar girls,” and almost all of them were (in Western parlance) prostitutes. The practice is significantly different (though every bit as heartbreaking) as it is here in the West. One of the women approached me with a polite smile and asked me what I was writing. I told her that I was writing a letter to my family and describing my experiences there in Subic Bay, that while the people smiled so much and were so welcoming, they really didn’t seem very happy at all.

Thanks to a moderate case of face blindness, I cannot remember her face, but I do remember that her expression changed in an instant, from courteous and kind to a deep, bitter anger. I remember her voice as she replied, “You tell them this is hell! You tell them that!” after which she turned on her heels and left. I never saw her again.

I wasn’t angered or offended at her outburst, but I was certainly troubled, and I spent a long time considering her words, at what had brought her to that junction in life, and what kind of emotional pain she must be carrying. It was only then that I began to recognize the enormity of the racial advantage that I had, that I’d carried since birth, what is today termed “white privilege.” I’d have to say that was the final straw, the one that began to break the burden of white racism and privilege I’d never realized I’d been carrying all my life.

OHF Weekly In your opinion, what’s the biggest obstacle to people changing their race-based thinking and actions for a more equitable worldview?

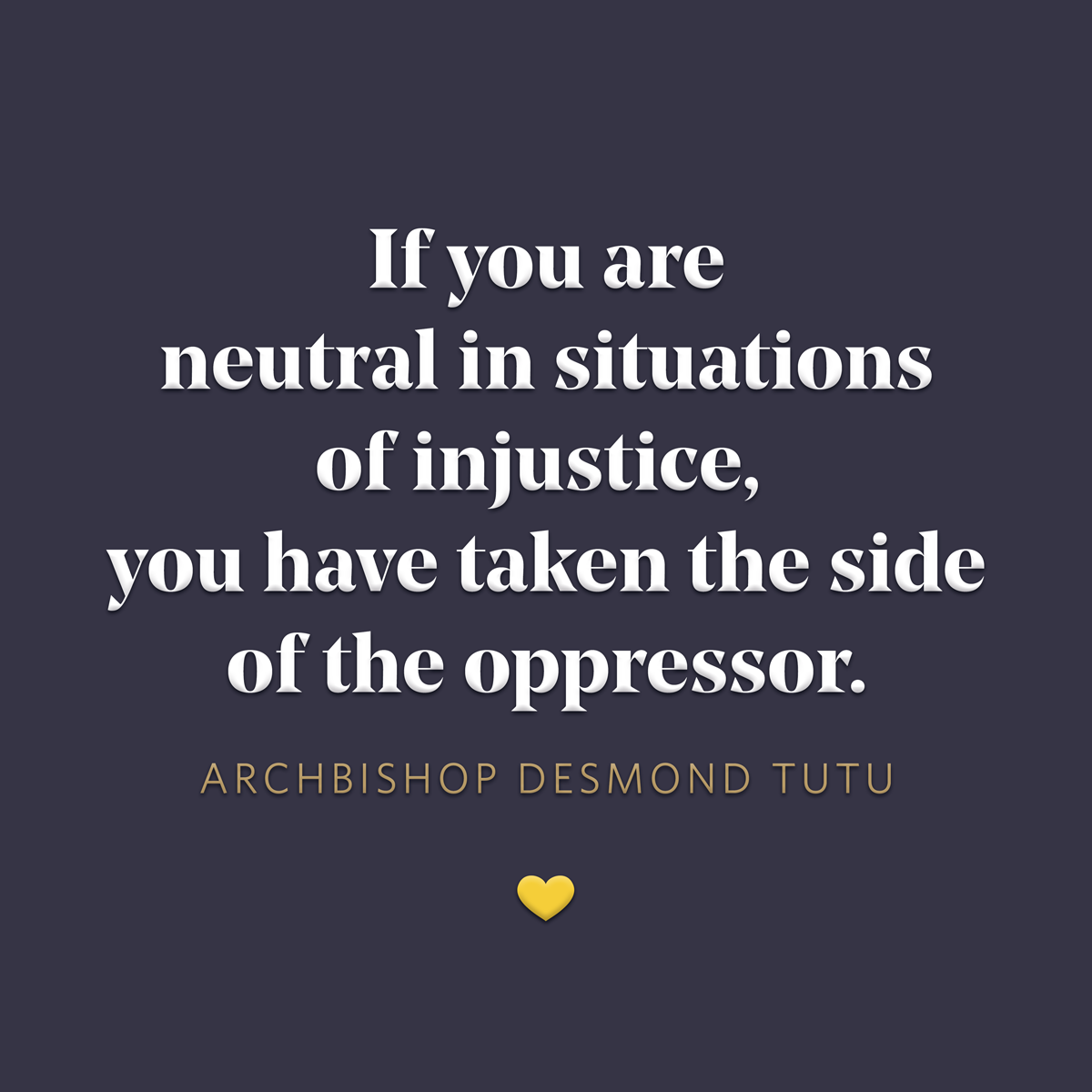

Glenn I’ve written many times that—as with the family and friends of my youth—the great majority of racists do not recognize their own racism for what it is. Almost all people believe themselves to be good and morally upright, and they try to find ways to excuse or justify their words and actions towards others, no matter how obviously wrong those words or actions may be. So it goes with white racists: they point to what they insist are acts of kindness or consideration that are “proof” they can’t be racist, and that their own opinions aren’t based on racism at all, but are instead simply the result of their own observations and experiences.

The proof of this lay in the near-certainty of how, when a politician, pundit, or celebrity is shown to said or done something racist, that individual will immediately and publicly disavow any hint of racism. “I can’t be racist—I have a Black friend” has become a nauseatingly common meme whenever this occurs. Others point to their interracial marriage and mixed-race children as hard evidence that they can’t be racist, but in my experience, even this is far from any guarantee that one is not racist, even against the race of one’s spouse.

For instance, in the U.S. Navy there is a strong contingent of Filipinos, mainly from our having had a large naval contingent based at Subic Bay for nearly eighty years. During that time a great many American sailors found spouses there, and I can personally attest that it was not uncommon to hear a sailor—whose wife was Filipino and whose children were mixed-race—make racist comments about Filipinos in general.

This example of a husband’s racism against the race of his spouse is at its most basic level directly attributable to the economic or military success and technological achievements of their respective races or ethnicities. Such success tends to engender the mindset that “we succeed because we’re better as a culture and as a race, or because we are the chosen people of God.” Such attitudes of national scale have been identified throughout recorded history, from the time of Moses to the rise of China today.

This dynamic can be described thusly: “In every nation or region, there is one and only one socioeconomically-dominant race or ethnicity, and it is that race or ethnicity that will commit the most—and the most egregious—acts of racism.”

For those who study racism and racial inequity, the importance of the rule described above cannot be understated. For example, by any rational measure, the great majority of racist acts in Western nations—and particularly in America—are committed by white people. Moreover, while white people are not the first to institute slavery based upon race or ethnicity (an early recorded instance of such was the bondage—the slavery—of the Hebrews in the time of Moses), we are the first who industrialized it, even in a sense applying the principles of mass production to the abhorrent practice. In America, white people fought a civil war to preserve slavery, and even afterward imposed the race-based Jim Crow laws on non-white people in general (and Black people in particular) for nearly a century.

That struggle of our better angels against our baser instincts is never-ending.

Bearing that in mind, the argument can—and often is—made that white people are by our nature racist. “By their works shall ye know them,” right? The problem, however, is that the declaration that “if one is white, one must be racist” is in and of itself a racist statement in that it attributes a negative trait to anyone of a particular race.

This is why the rule described earlier is so important, for it describes in simple terms why American white people tend to be racist while at the same time showing how such is not an inevitable product of one’s race or ethnicity. Examples of this dynamic are found in every nation, from the dominant Han Chinese against the Uighurs and Tibetansm to the high-class Brahmins in India against the Dalits—the “untouchables,” to the aristocratic Tutsis against the less-successful Hutus in Rwanda, or the Hispanics of Central and South America against the indigenous peoples of their respective nations.

Unfortunately, human nature being what it is, as long as there are different races, ethnicities, cultures, and religions, and as long as any one of those societal subsets is richer, more powerful, or more influential than any of the others, socioeconomically-based racism and prejudice will exist. Indeed, the fight against racism and prejudice is Sisyphean, for as soon as the great rock is pushed to the summit—signifying, if you will, the triumph of righteous morality over racism—that rock will roll back to the bottom and the struggle will begin once more, the cycle repeating itself until the end of time.

That struggle of our better angels against our baser instincts is never-ending. That does not by any means imply we should not continue this most important of all the good fights we face as a species.

OHF Weekly To write about racism, racial inequity, oppression, and the like, writers have to dig deep into a disconcerting reality, sometimes that involves self-examination. What’s been your most revealing article and why?

Glenn I would say it’s “When Leaving Racism Means Leaving One’s Family” in which I tell in greater detail my journey out of racism. I describe how racism was so deeply woven in my family’s heritage all the way back to the Civil War, how we had known someone who was for a time the most powerful racist in America, and how we excused our words and actions with an all too-transparent veneer of assumed morality.

Having written on the subject many times, it is increasingly easy to point out the racist faults and failings of my family and myself, and of the community in which I was raised. But the journey of self-discovery, of the gradual and saddening realization of just how wrong, how racist we all were, was not so easy. It is perfectly natural for a person to want to be proud of his or her family, heritage, and culture—but to learn that one’s family had not just engaged in but willfully embraced a societal paradigm rotten to its core, and then to reject one’s family, heritage, and culture is not natural.

Even today, I’m still learning the unexpected costs of that choice even as I watch my children and grandchildren grow.

This rejection didn’t occur overnight; indeed, it was a process that took decades. It felt as if I was cutting myself off from everything I had known. It is said that in any journey, the first step is the hardest. For myself, the first step on this journey wasn’t answering the hard questions of race, culture, and morality, but whether the questions should be asked at all. It’s not unlike looking at a door, behind which lay not just uncertainty, but realization of at least partial responsibility for a great and pernicious evil, and acceptance of the shame and humiliation carried by that responsibility. One may choose to leave closed that door, to turn away and remain within the comforting embrace of the life one has always known. But once that door is opened and one steps across the threshold, one cannot turn back, not ever, regardless of the cost.

I’ve mentioned Moses twice before in my answers, but this, too, is the kind of choice he faced: whether to remain in the comfort of what he had always known or to reject what he could now clearly see was an evil practice of bondage and slavery. I do not and cannot by any means presume to compare myself to Moses. Instead, my intention is to point to him as the most famous example of those who have had to make such a choice. Today on social media one can find quite a few who have made that same kind of choice, who have learned what it is like to force oneself to reject one’s family and walk alone on a path one’s forebearers did not dare to tread.

Even today, I’m still learning the unexpected costs of that choice even as I watch my children and grandchildren grow. Most children are raised to respect and value the lives not only of their mothers and fathers but also the lives of their grandparents and ancestry before them. They consider their familial heritage, the blood carried in their veins giving them a sense of belonging to times and places far removed where their ancestors once walked. I suspect we all feel that urge to say, “That’s the place where my family, my people came from, and it’s part of what made me what I am today,” whether that place was the pastoral Tuscan countryside, the endless savanna of the Serengeti, or the densely packed urban cityscapes of East or South Asia.

By rejecting my birth family and the culture and heritage of my youth, I have in a sense not only robbed my children and grandchildren of the pride and sense of belonging they otherwise might have had from my side of their family, but—by ensuring they know the reasons for my rejection—have to an extent even poisoned their respective perceptions of my ancestry and cultural heritage.

Of course, one could flippantly refer to this as an example of the Law of Unintended Consequences, but to do so would be disingenuous, for the choice was never a zero-sum game of profit and loss, but a determination of right against wrong, of fact instead of fiction, of the good of universal human dignity over the evil heritage of slavery and Jim Crow.

OHF Weekly With all that’s going on in the world, why do you still write about racial equity, allyship, and inclusion?

Glenn How can I not do so? For all the wrongs that my birth family and I committed across the generations, it would be not just wrong, but dishonorable to try to sweep our sins under the carpet of obstinate silence.

Of course, nothing I do could ever make up for the 150 years of my family’s support of racism of which I am aware, but I can try. More importantly, I continue to teach my sons to reject racism, to stand against it, and to teach their own children to do the same. And as far as my own Southern heritage is concerned, let it be forgotten except as a subject for scorn and opprobrium, an object lesson in how men may proclaim themselves paragons of virtue even as they engage in the basest of iniquities.

OHF Weekly Glenn, thanks for your time.

Glenn My pleasure. Thank you.

Photos courtesy of Glenn Rocess.

Also by Glenn Rocess

Subscribe to OHF Weekly

Never miss another OHF Weekly article or newsletter again. Sign up for email delivery. The best part? It’s free. And free is always in the budget.

Final Thoughts

Love one another.

Member discussion