There are over 1,700 monuments to the Confederacy in America today, from the four corners of the continental United States to most of the states in between, and including several of the former Union states. The Confederate flag is found almost exclusively in white homes and businesses, as stickers on cars and trucks, and even as part of the Mississippi state flag.

This is notable because America is the only nation today where those who fought a civil war against that nation are memorialized and even glorified with government approval and at the taxpayers’ expense. Those who support keeping Confederate monuments on public lands commonly make the argument that Confederates were Americans. Below is one such example of the argument:

The [Confederate] flag in dispute flew over the forces of the Confederate States of America, not the Confederate States of the South. The invocation of “America” in the name of the seceded nation was no accident, no casual holdover. It was deliberate. They were us and we were them—all Americans.

The founders of the Confederacy understood themselves as the real Americans, as those who had kept faith with the real American Constitution, as opposed to the compromise-laden failure enacted in 1789. They cast themselves as the true Americans, the true inheritors of the Revolutionary legacy of ordered liberty and political sovereignty. They were the champions of liberty, standing firm against the usurpations of the Northern hordes.

—Pittsburgh Post Gazette

The great majority of reactions to the preceding argument will be either positive or negative. Those who want to preserve the monuments and the display of the Confederate flag will agree, and those who want the monuments and flag off public grounds and off the taxpayers’ hands will disagree. Very few indeed will have held both opinions. I’m one of those who have.

As I’ve often written, I grew up in the very deepest of the Deep South, in the Mississippi Delta. The cemetery at the local Southern Baptist church holds the bones of my direct family line all the way back to 1870. I was steeped in southern culture which by its very nature includes the glorification of the “Lost Cause” of the Confederacy. I sang loud-and-proud what was until 2016 the unofficial theme song of the Ole Miss Rebels, “Dixie.”

To most white people raised in the Deep South, that “Lost Cause” isn’t about slavery at all, but about their own freedom (yeah, ‘freedom’), being their own nation with their own laws and way of life, no matter the cost to others. Many of them identified strongly with William Wallace in the movie Braveheart for that very reason.

As a general rule, when in conflict with others, always try to bear in mind that the other person honestly believes himself or herself to be good and right. I’ve found it’s usually more effective in such discussions to acknowledge the other person’s earnestness and good intentions, for doing so tends to lead to more respectful and productive debate, even if you believe in your heart that the other person is as racist as the day is long.

This is called diplomacy, what Churchill pithily described as “the ability to tell someone to go to hell in such a way that they look forward to the trip.”

Perhaps it might be beneficial to use the metaphor of a firearm. If the weapon itself is one’s desire to change the other person’s mind, and if diplomacy is the ability to aim, then historical facts and data that disprove rank assumption are the ammunition.

Here, then, is your ammo when it comes to discussions about Confederate monuments and the Confederate flag:

“The Confederates weren’t traitors—they were Americans!”

The response to this claim is the definition of treason which, as defined by Cornell Law School, refers to anyone who, owing allegiance to America, wages war against America. Every Confederate soldier was by definition committing treason. Are we then to have monuments to traitors, or fly their flag in places of honor?

“How could Confederate soldiers be traitors? The Confederacy had declared its own independence!”

The response here is even simpler: “Since when should a nation’s taxpayers pay for monuments to another country who waged war on that nation, much less fly the offending nation’s flag in places of honor?”

“The Civil War wasn’t about slavery—it was about states’ rights!”

According to leaders during the Civil War, it was very much about slavery:

- Alexander Stephens, Vice President of the Confederacy, in what has since been called his “Cornerstone Speech”: “[Slavery] was the immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution.”

- Mississippi Articles of Secession: “Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery—the greatest material interest of the world . . . There was no choice left us but submission to the mandates of abolition, or a dissolution of the Union, whose principles had been subverted to work out our ruin.”

- President Abraham Lincoln, in his second inaugural address: “All knew that [slavery] was somehow the cause of the war.”

“We know slavery was wrong, and the Confederacy was wrong. Those monuments and the flag are only there to educate us, to remind us of our past and our heritage.”

Actually, no. A spike in the number of monuments occurred during two distinct periods. The first coincided with the enactment of Jim Crow laws in 1877 and lasted through the end of World War II, with most situated on courthouses and government land. The second period began in the mid-1950s and lasted through the late 1960s. But two landmark events transpired concurrently: Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 and the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Apologists claim such were erected on school grounds to help educate children, but the fact that so many immediately followed the Brown decision invalidates such a claim.

In other words, the erection of the monuments was quite literally an effort to preserve white supremacy by providing grand-scale tributes in prominent locations to serve as physical reminders of white supremacy. Sadly, the building of such monuments has continued through the present day, with at least fifteen being built since 2010, two of which were on courthouse grounds.

“Why do you have to keep shoving slavery and Jim Crow in my face? I wasn’t even alive then!”

This is perhaps the most common retort and is usually made in frustration or even anger. Diplomacy is key here.

- The proper response is to ask in return why they insist on reminding Blacks of the slavery and Jim Crow laws that were forced upon them. After all, that’s what those monuments and that flag were meant to do in the first place, to remind Blacks of slavery, Jim Crow, and white supremacy.

Most white Confederate sympathizers in the Deep South believe in the Confederacy’s “Lost Cause” ethos, but it’s more of a mythos. Southern hospitality is real, but the racist tyranny the Deep South imposed and still attempts to impose is just as real.

There are nations—Russia, China, and France come to mind—which celebrate past tyrannies wherein so many of their own populations were killed or enslaved. But there are more nations—Italy, Uganda, Cambodia, Germany, and many others—that learned to not glorify tyranny, to not celebrate the grand-scale crimes against humanity of their respective pasts. Our nation’s history clearly shows that we have thus far chosen the former example.

Fortunately, times change and societies change, and such choices can never be written in stone. Most Americans acknowledge slavery as this nation’s original sin and greatest crime against humanity, even without the added iniquity of a century of Jim Crow laws. We do not look wistfully back at the Japanese Internment or the Chinese Exclusion Act. We no longer see General Custer as a hero, but as someone who received richly deserved comeuppance during the Native American genocide.

Why, then, does a significant portion of the American population to this day still lionize those who literally committed treason in order to preserve and perpetuate white supremacy? America has learned to reject the crimes, but has not yet learned to reject those who committed those crimes.

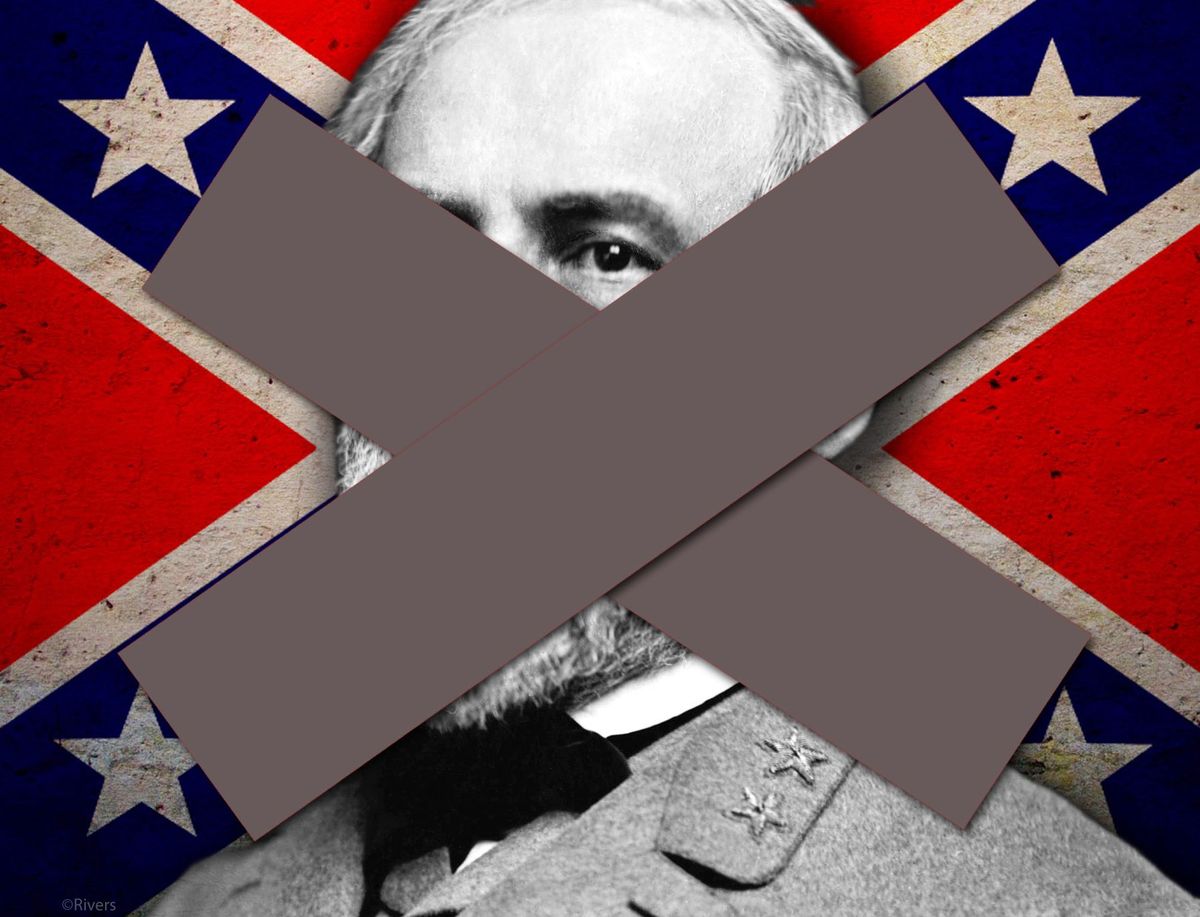

It’s long past time that our nation came to grips with the prejudice that to this day still poisons our national discourse. The Confederate flag and monuments to Confederate leaders need to be removed from public property. More importantly, the government needs to ensure that every schoolchild is shown that even by the laws of the time, those who fought for the Confederacy were not heroes, but traitors.

Yes, traitors.

And that those traitors fought to preserve their “right” to own men, women, and children as property, and to do with those enslaved people as they would, up to and including rape and murder. No, such men must not be lionized. Even Lee, as cruel and brutal as we now know him to have been, knew there should be no monuments to him, or to anyone of the Confederacy which had been defeated on the field of battle. When asked to attend a meeting concerning such monuments, Lee replied, as documented by New York Times:

I think it wiser, moreover, not to keep open the sores of war but to follow the examples of those nations who endeavored to obliterate the marks of civil strife, to commit to oblivion the feelings.

Digital illustration by Clay Rivers.

Member discussion