Letter from the Editor

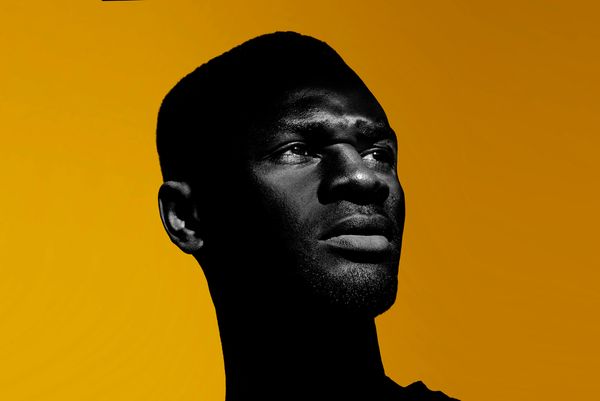

Justice Should Never Be Black or White

Check dictionaries for their interpretation of “justice” and you’ll come across definitions such as the quality of being fair and reasonable (my laptop); the process or result of using laws to fairly judge and punish crimes and criminals (Merriam-Webster); and fairness in the way people are dealt with (Cambridge Dictionary). All nice. All sterile. All lacking, but decent starting points for our purposes.

If you were to ask most Black, Indigenous, and People of Color about the concept of justice, themes of personal and group accountability, making amends for the wrongs done, restoring the damaged item to its previous condition, and a sprinkling of mercy would be added to the mix. I say this because BIPOC are all too familiar with justice’s opposite: injustice.

When we look at the Ocoee Massacre, no one was held accountable for the razing of Black homes, churches, businesses, and fertile orange groves or the lynching of July Perry. Lands rightfully owned by Ocoee’s Black residents that were stolen from them were not returned. Most anyone would say that the residents and descendants of the Ocoee residents murdered or run out of town did not receive justice.

The converse holds true in the matter of Bernie Madoff’s Ponzi schemes. Madoff was held accountable in court, sentenced, and generous reparations paid to his victims ($3.762B or 81.35% of losses restored). Anyone would say the victims received justice. And then some.

People of Color in general, and Black people in particular, are either flat-out denied, get the short end of the stick, or wind up with a knee on their neck when it comes to receiving justice in America’s courts. Every time a Black victim becomes a hashtag rally cry for justice, we see ourselves and loved ones.

So when defendants like Chauvin, the McMichaels, and Bryan are held accountable in courts, we take note because it is not the norm. Not for us. For me, these convictions, while noteworthy, only fit part of the Black rubric for justice, as there is no way to restore the lives of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Emmett Till, or thousands of murdered victims.

This is the reality of our experience that burns within our bones.

In a conversation I had with a white friend, he said something that seems endemic to white thinking: What is justice, if not hope persevering?

I think justice for most white people is a different concept than for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color. I get the impression their definition of justice is something theoretical, off in the distance, they can reach out and touch/access at will should the need arise. Kinda like the spirit, Beetlejuice. It’s as if, for us to receive anything that even resembles justice, we have to first crawl on our hands and knees over obstacles like broken glass.

Of course, white folks will be afforded a measure of mercy during a traffic stop if not given a wink and a nod and sent on their way. Of course, they’ll be believed if they call the cops on a group of innocent Black boys and justice will most definitely be served, come what may. (Research the Central Park Five.) Of course, they’ll receive the benefit of the doubt, when there’s no doubt of guilt. (Research the murders of Emmett Till and Trayvon Martin.)

We don’t live in a society in which “justice rolls down like waters and righteous like a mighty stream.” (You know Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. borrowed that from scripture, right? Now you do.) But it doesn’t mean we shouldn’t strive to live in a world in which justice (accountability, restoration, mercy, and love) are extended equally to all.

If you haven’t jettisoned out of this letter from the editor yet, good. Know that I’m not intimating that all white people have no clue as to the nature of justice or that white folks cannot experience injustice. What I am saying is that justice in America is blind, unless there’s a Black person involved. Then all bets and blindfolds are off. Rarely do white folks have to run the gauntlet of biases because of the color of their skin.

Matters of race, racism, and justice for Black people have changed to a degree over the years, markedly in some areas and incrementally in others. These changes didn’t take place simply because Black people said, “We’ve had enough, stop the injustice.” Dismantling racism can’t be done by Black people alone. We can sound the alarm that these injustices are being perpetrated, and we have for 400 years, but only white folks can prevent this forest fire.

Because white people are making increasing stands for justice, old ways of thinking and living are changing. But we still have a long way to go.

The reason for our “OHF Family Tree” series of interviews is to show you why and how our writers arrived at their brand of activism. This week, OHF Weekly contributing writer Michael Greiner shares his motivations for seeking justice in his professional and personal life.

Stay tuned! Next week we begin our Black History Month series.

Love one another.

Clay Rivers

OHF Weekly Editor-in-Chief

The “OHF Family Tree” Interview: Michael Greiner

By OHF Weekly Editors

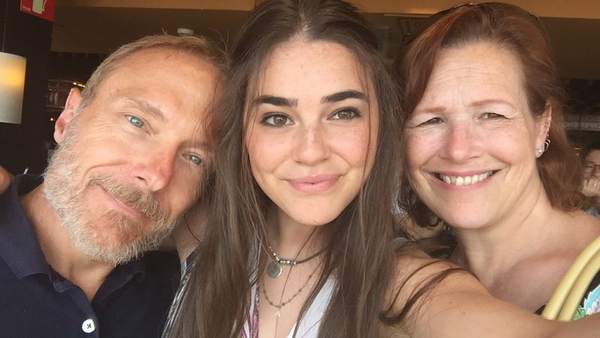

Political activist, lawyer, college professor, and OHF Weekly contributor Michael Greiner believes politics, government, economics, and the law are inextricably linked to racial equity. And he’s compelled to help you understand that. Here’s why.

OHF Weekly In four sentences, how would you tell us you’re on Team Racial Equity without saying you’re on Team Racial Equity?

Michael Greiner I believe in the value of all people and in justice. I know that the privileges I enjoy as a cisgender white man in the United States are not based on merit. Instead, these are blessings, and as Jesus said, those to whom much is given, much is expected. At a minimum, then, my empathy and support are expected for those who have not received the same advantages.

OHF Weekly What was the moment you decided to write and publish your works for the world to read?

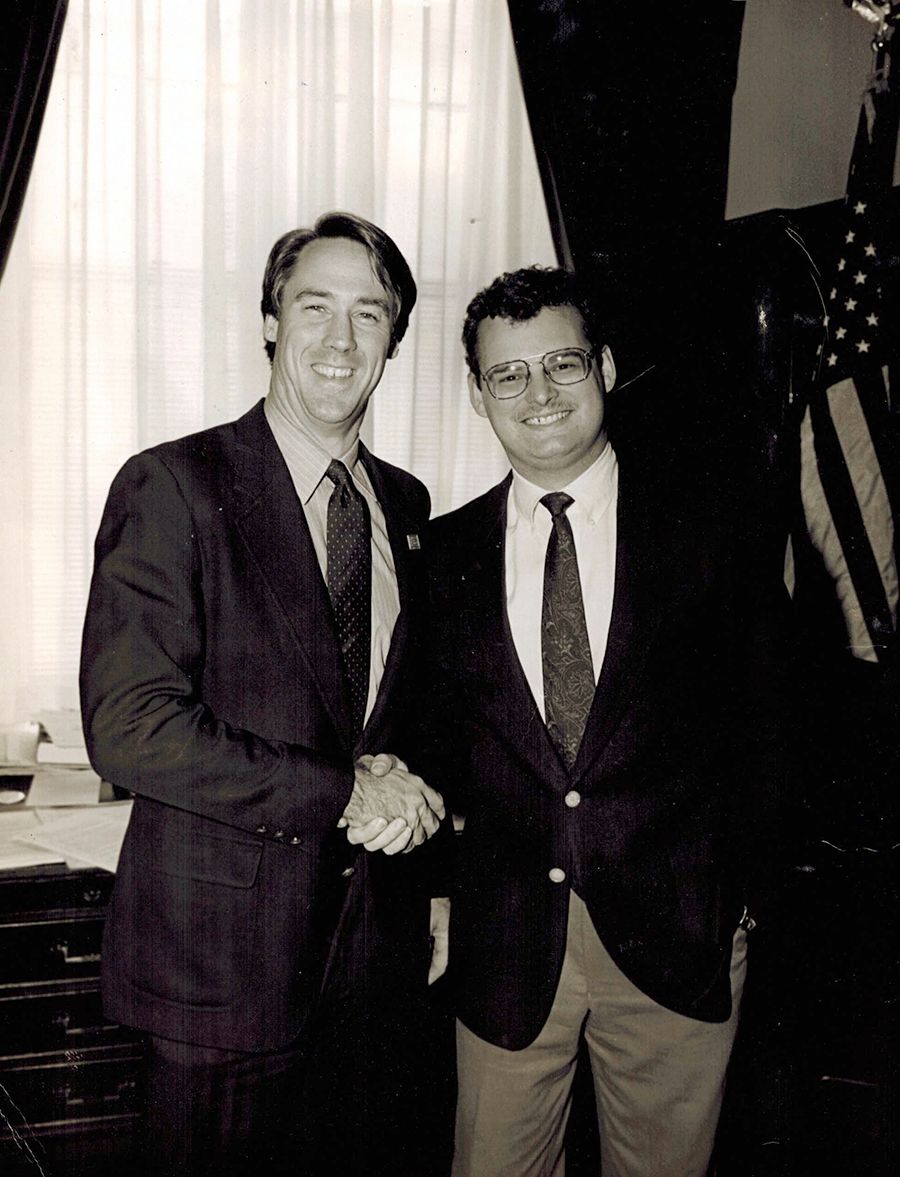

Michael As a child, I remember writing books for my family. But then as I got into high school, I chafed over having to learn the rules. It really wasn't until after college, when I was tasked to write a speech for a Congressman I was working for, that I first discovered my true passion: writing about politics and policy. I was amazed that others appreciated my writing and that this kind of writing did not come easily to others. I can't write fiction or poetry to save my life. But when I am moved by my outrage over injustice, the words just flow out of me.

I have an obligation to use these gifts ... to fight with love for just for all God’s people.

My desire to write is driven by my faith. My mother instilled in me a deep faith in God that has only gotten stronger as I’ve grown. One of her favorite stories from the Bible is the parable of the talents, where Jesus described a master giving “talents” to his servants. The two who invested the talents and made them grow he praised. But the servant who hid the talent to protect it he called “wicked and slothful.”

Like that third servant, I was afraid to write and publish my thoughts. And yet I knew that the ability to communicate logically and coherently is a blessing God gave me. God has also given me the opportunity to learn about the world through educational opportunities unavailable to most people. As such, I have an obligation to use these gifts for the glory of God. And to me, the best way to glorify God is to fight with love for justice for all of God’s people. In my reading of the Bible, that is what Jesus would do.

OHF Weekly In your opinion, what’s the biggest obstacle to people changing their race-based thinking and actions for a more equitable worldview?

Michael The biggest obstacle to people changing their viewpoints for a more equitable worldview is that the myths and stories that we tell ourselves lock us into our current ways of thinking.

That is, it is so easy for people like me, white, cisgendered men, to believe somehow, we deserve our place in this position of privilege. Because we grow up in a world in which our privilege is assumed, we tend not to see it as anything special and assume it as well. It is the story we have been taught and it is the story that we believe.

To get people who are generally self-centered to step out of themselves sufficiently to see that their privilege is unearned and unjust, and even to get them to see that they have privilege at all, requires a feat of empathy that appears beyond many. It requires abandoning the stories we believe that have comforted and guided us.

The truth is that thinking deeply about racism within society is something that most white people do not do for several reasons. First, it makes them uncomfortable. As can been seen in proposed legislation in Florida and other states, white people don’t want to face the injustice that we, especially straight white men, have inflicted upon just about everyone else because it makes them question their own behavior, and whether the behavior of their ancestors is worthy of respect.

Second, it challenges our assumptions. We have these myths that bind us together, and they include stories implying the near-sainthood of the Founding Fathers. But these founders were not saints; in many cases, they weren’t even good people. Correcting such misguided myths can be deeply unsettling to many people.

Finally, they don’t have the time. Most people are busy with their own lives, trying to take care of themselves and their families from one day to the next. To ask them to consider concepts such as injustice suffered by others, or to put themselves in the place of others, is something many white people just don’t want to take the time to do, simply put, because injustice is rarely a thing we are forced to contend with on any meaningful level. That is asking them to make a new story, one that might not center them but instead center others.

I have been blessed through my experience, my relationships, and my education to be able to see the process through which racism, sexism and all the other isms imprison our society–even those who supposedly benefit from the system. In my writing, I seek to share the insights I have been privileged to see so that others who might not have the time or the inclination to think deeply about these problems might become aware that there is a better way to live together. In so doing, I hope that we can embrace truths to bind us together as a society, legacies that are rooted in the idea of equity and justice for all rather than paternalistic, racist norms.

OHF Weekly To write about racism, racial inequity, oppression, and the like, writers have to dig deep into a disconcerting reality, sometimes that involves self examination. What’s been your most revealing article and why?

In some respects, I lived a charmed life. I [am a white male who] grew up in a well-educated middle-class family and lived in upper-middle-class suburbs throughout my youth. It always seemed that my experience was the norm because it was the experience of everybody I knew. While I considered myself progressive and was outraged over injustice, my reality was formed based upon the environment in which I grew up.

I wasn’t really exposed to people with a different background from my own until I attended college—and this in the 1980s. I met gay activists, Black activists, and feminist activists. These people confronted me and forced me to question the reality I had come to accept. While it was just a beginning, it helped me understand different perspectives from my own.

I am infuriated by those who act as if Jesus encouraged selfish, unethical capitalism.

At the time, I could have chosen either of two responses to this challenge. I could have run away and dug myself into my beliefs as so many choose to do. Instead, I accepted this criticism and sought to learn from it. The people who were raising these issues with me were outstanding individuals whose point of view I could not simply dismiss. This choice set up a pattern throughout my life where I have endeavored to understand the different perspectives.

My most personal article would be “Did God help elect Trump?” This article is my take on the eternal question of how can a good and loving God allow bad things to happen. To understand this problem, I turned to one of my heroes, President Abraham Lincoln, whose second inaugural address is one of the most powerful speeches ever given. In that speech, given at a time when the United States was embroiled in its bloody Civil War, he argued that we do not have the right to question the purposes of the Lord. What we owe God, instead, are faith and our best efforts. In that article, I pledged both those things, and continue to do so, despite what often seems a hopeless situation.

OHF Weekly What is the one thing, one principle, you’d like for your readers to take with them from your body of work on racial equity and why?

Michael God is not racist. God loves all of us equally. I believe Martin Luther King, Jr. was a prophet sent to share the Word of God with us, and that Word cries out for justice and love. I am infuriated by those who act as if Jesus encouraged selfish, unethical capitalism. Their understanding of the Bible is deeply flawed, and I wish more people would see that.

I believe that God operates through all of us and through the world in which we live. Some people of faith reject science because it seems to question God’s place in our world. I, however, love science because it reveals the mechanisms through which God impacts our world. Knowing about evolution, or where babies come from, or how the universe was formed does not diminish their miraculous nature. If anything, most scientists are in awe of the revelations that come from their research, and more than a few reject the false choice of science versus faith. They can see that the miraculous way our universe operates reveals the power of God; it does not undermine it.

I have spent my life as a social scientist, studying how people interact and the systems we set up to manage these relationships, especially in larger societies. When we as a society set up these systems, we make certain choices. These choices can be driven by selfishness, or they can be driven by love. Unfortunately, most of our society is based upon the former, and my hope is to move it to the latter.

People are not unique in developing hierarchical societies in which one group tries to impose its will upon others. In fact, research into the animal kingdom has revealed how common such behavior is, and how we as people are truly part of the animal kingdom, not separate from it as was previously assumed. That said, however, we have been given the ability to make choices other animals might not have the cognitive ability to make. As a result, I want to push us to change society into one where those choices are based upon love, not selfishness.

In my late teens and early twenties, I went through a crisis of faith. I had questions about how God can allow so much injustice to exist. The answers I received from many people of faith were unsatisfactory, urging me to have faith with my heart, not my head. But God gave us the ability to reason, and if God did not want us to use that ability, why did we get it?

As I have gotten older, I have come to understand that thinking deeply about society actually reveals God’s influence, but it also places upon all well-meaning people the burden to seek God’s justice. We all have the choice as to whether we will choose love or selfishness.

I think it is clear what God wants us to choose, and I have found that a rational, logical understanding of the deep nuances in our society leads us toward that choice. That is why I share with others the nature of society that they might otherwise choose not to see, or be unable to see.

OHF Weekly With all that’s going on in the world, why do you still write about racial equity, allyship, and inclusion?

Michael I don’t have a choice. I do the work I do because I cannot tolerate the rampant injustice today. I have no choice but to try to change it, and so, I continue to do so. My father was an academic with a deep passion for academic honesty and justice. He believed what mattered was what you did and how hard you worked at it. Characteristics such as the color of your skin, your gender, or any other personal details are irrelevant. Where my mother instilled in me a deep faith, my father instilled in me a passion for justice. As a result, seeing injustice in the world is intolerable to me, and fighting that injustice is something I have no choice but to do all that I can.

OHF Weekly Michael, thanks for your time.

Michael Happy to help.

Photos courtesy of Michael Greiner.

The Michael Greiner Short List

Want to read more works by OHF Weekly writer Michael Greiner? Here are three of our favorites!

NEW Winter Merch

Fend off Old Man Winter with our collegiate-style sweatshirt in navy. Get yours now at our OHF Shop at Bonfire.

Final Thoughts

Love one another.

Top photo by Julian Wan on Unsplash