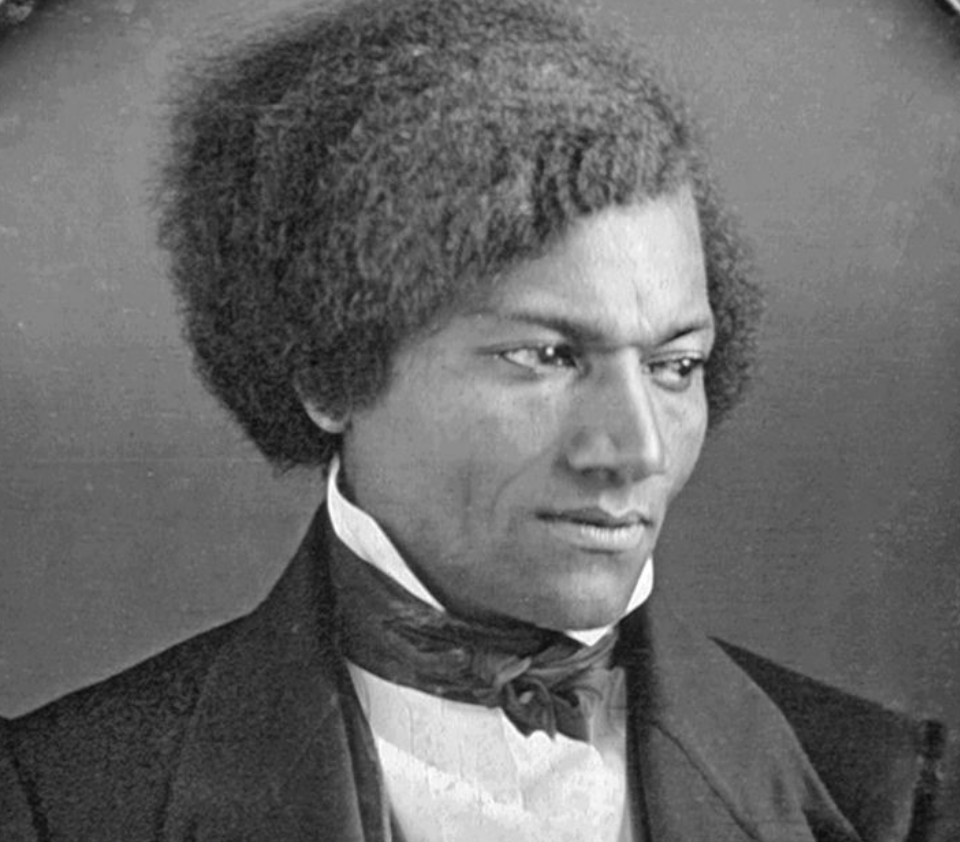

Orator, writer, and statesman Frederick Douglass in the 1840s. After escaping bondage, he became a leading advocate for the emancipation and civil rights of African Americans as well as all oppressed people. Image source.

During his lifetime, Frederick Douglass lectured not only on anti-slavery but also temperance, women’s rights, racism, and social justice for all; he edited and owned newspapers, advised presidents, and wrote three versions of his life story. The publication in 1845 of his first and most popular autobiography — Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave—became a bestseller, especially in Europe, levering him to international prominence and triggering his visit to Ireland that same year.

To prove the authenticity of his words in the Narrative, Douglass gave details of personal information which put him at risk of being recaptured into enslavement. Though he was living in one of the so-called Free States, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 meant that Douglass remained in constant danger.

So, persuaded by his abolitionist friends, he opted for a period of exile in Ireland and Great Britain, which lasted almost two years. He first went to Ireland in August 1845 where he was warmly welcomed and, for the first time in his life, he experienced what it meant to be treated as equal.

Shared Brilliance, Champions of Human Rights, and a Universal Desire for Freedom

“I despise any government which, while it boasts of liberty, is guilty of slavery, the greatest crime that can be committed by humanity against humanity.” — Daniel O’Connell in 1845, the year of Douglass’s arrival in Ireland.

Though brief, one of the highlights of Douglass’s visit to Ireland was meeting his life-long hero and Ireland’s Liberator, Daniel O’Connell, the acknowledged political leader of Ireland’s Roman Catholic majority in the first half of the 19th Century. A great achievement of his was to “liberate” the Catholic people from the oppressive Penal Laws, enabling Irish Catholics to sit in parliament and hold senior offices of state.

An important and influential figure in the history of Irish politics, O’Connell, like his admirer, Douglass, was renowned for his considerable abilities as an orator and his charismatic personality. His flaming speeches on social justice inspired Douglass.

In his introduction to The Narrative, William Lloyd Garrison, the prominent American abolitionist and social reformer best known for his anti-slavery newspaper The Liberator, referred to O’Connell as “the distinguished advocate of universal emancipation, and the mightiest champion of prostrate but not conquered Ireland.”

Thus, a connection between the veteran Irish abolitionist and the young rising star of American anti-slavery was already established before Douglass set sail for Ireland.

Frederick Douglass’s arrival in Ireland was well-timed. Though physically ailing, O’Connell was still politically influential and had positioned himself as one of Europe’s foremost opponents of enslavement. His views had been embraced by many Irish people, hence Douglass’s enthusiastic welcome.

Had he visited a year or two later, O’Connell’s influence would have been waning and the severe impact of the Great Famine would have had its grip on the country, depriving Frederick Douglass of a socio-political platform and support for his anti-slavery crusade.

The zenith of Douglass’s stay in Dublin was hearing O’Connell speak at a Repeal meeting focussed on restoring the Irish parliament. Douglass was greatly impressed by O’Connell’s seventy-five-minute speech, describing it in his report to The Liberator, as:

“. . . skillfully delivered, powerful in its logic, majestic in its rhetoric, biting in its sarcasm, melting in its pathos, and burning in its rebukes.”

In the same way, as Douglass came to realise that human suffering was a global plight to be denounced and eliminated, O’Connell’s stance on social and political justice for all included the abolishment of enslavement, a stance Douglass further reported on with this excerpt from O’Connell’s speech:

“I have been assailed for attacking the American Institution as it is called—negro slavery. I am not ashamed of that attack. I do not shrink from it. I am the advocate of civil and religious liberty, all over the globe, and wherever tyranny exists, I am the foe of the tyrant.”

Though not a politically popular position, O’Connell had long been a steadfast opponent of enslavement which he verbally attacked as “a foul stain” on America’s character. He caused a stir in the 1830s by publicly accusing the American Ambassador in London of being “a slave breeder,” after which the Ambassador threatened to challenge O’Connell to a duel.

O’Connell focused on the suffering of Black people, particularly the despair of Black mothers knowing their children would be taken from them and put into enslavement.

He also attacked America’s Founding Fathers, accusing them of lacking the “moral courage” to abolish enslavement. O’Connell’s uncompromising stance alienated him from many Irish Americans and in 1843 he decided to reject financial support from those who backed enslavement.

Though O’Connell failed in his campaign for Repeal, aimed at breaking political ties with Britain, he was successful in emboldening the Catholic Irish. In his view, he could walk down any street in Ireland and pick out Catholics “because they were the ones who would shuffle, had bad posture, were afraid of meeting your gaze, beaten down.”

For a people systematically reduced by the Penal Laws to poverty and ignorance by having their land, possessions, religion, culture, and access to education taken away, raising one’s head was considered a risk. But O’Connell, with his powerful words, restored their self-esteem.

It was here, too, that Douglass’s famous plea to agitate was spawned—borrowed from O’Connell’s appeal to the Irish public to “agitate” against their oppressors.

Douglass, who saw many parallels with the plight of the enslaved, was mightily impressed by O’Connell and embraced much of his thinking.

On that evening in Dublin, after the introductions, the 70-year-old O’Connell encouraged 27-year-old Douglass to speak to the audience. This he did, fascinating them with his life experience, vast knowledge, and abolitionist passion. Douglass revealed that as an enslaved man, he had known of O’Connell and was moved to say:

“I feel grateful to him for his voice has made American slavery shake to its centre—I am determined wherever I go, and whatever position I may fill, to speak with grateful emotions of Mr. O’Connell’s labours. I heard his denunciation of slavery, I heard my master curse him, and therefore I loved him.”

It was here, too, that Douglass’s famous plea to agitate was spawned—borrowed from O’Connell’s appeal to the Irish public to “agitate” against their oppressors. And so, concluding his speech, Douglass not only praised O’Connell, but declared that his enslaved compatriots also required “a Black O’Connell” to liberate them:

“The poor trampled slave of Carolina had heard the name of the Liberator with joy and hope, and he himself had heard the wish that some black O’Connell would rise up amongst his countrymen, and cry ‘Agitate, agitate, agitate’.”

A pioneer of peaceful protest, O’Connell was also a believer in non-violent political change.

At home, Frederick Douglass would often refer to him in his anti-slavery speeches, viewing O’Connell’s efforts on behalf of Irish freedom as an instructive tale for Blacks and the oppressed worldwide:

Controversy

Douglass also had his controversial moments. He often spoke about the anti-Christian nature of slavery. He criticised established religion and, in particular, America’s Protestant Churches for their support of enslavement. This went down well with his Catholic audience, with him conveniently omitting that in America the Catholic Church participated in, and justified, enslavement and the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

Not wanting, however, to be portrayed as anti-religion, Douglass declared in one of his last Dublin speeches:

“I love the religion of Jesus which is pure and peaceable. . . . but I hate a religion which tears the wife from the husband — which separates the child from the parent — which covers the backs of men and women with bloody scars. . . . it is not Christianity, it is of the devil. I ask you to hate it too, and to assist me in putting in its place the religion of Jesus.”

Protestant-Catholic tensions in Ireland proved a challenge for Douglass and difficult to navigate, and unlike American skin colour differences, were not as obvious. Wishing to impress audiences of either religion, Irish nationalists, and British loyalists vital to the abolitionist movement, Douglass sometimes got caught up in controversies beyond his experience and abolitionist message.

Despite paying tribute to O’Connell in Protestant Belfast, he strategically avoided mentioning O’Connell’s cause, or the plight of Catholics, so as not to alienate Protestant audiences.

Douglass also stressed that the situation of the Irish, while they suffered from “deprivation and discrimination,” was nothing like what he had endured in enslavement. Irish people had the freedom at least to leave and seek new lives in America and elsewhere.

Stating “there was nothing like American slavery on the soil on which he now stood” proved difficult for those who believed the Irish system of “slavery” under British oppression should be addressed first.

Cork City

Continuing his journey, Douglass stayed in the southern coastal city of Corkfor several weeks in 1845. The city had a population of around 100,000 and, initiated by the Quakers, multiple abolitionist groups active since the 1700s.

His visit was organized by the Cork Anti-Slavery Society (CASS) and its auxiliary branch, the Cork Ladies Anti-Slavery Society (CLASS).

On his arrival, Douglass was warmly received by Cork City’s anti-slavery societies. In a letter to William Lloyd Garrison, he described a soirée hosted in his honour by the famed “Apostle of Temperance” Father Mathew:

“No one . . . seemed to be shocked or disturbed at my dark presence. No one seemed to feel himself contaminated by contact with me. I think it would be difficult to get the same number of persons together in any of our New England cities, without some democratic nose growing deformed at my approach. But then you know white people in America are whiter, purer, and better than the people here.”

Women were instrumental in the anti-slavery movement on both sides of the Atlantic and provided the “great silent army” of volunteers and fundraisers. To have an ex-enslaved person journey all the way from the land of the enslaved to lecture on the abolishment of this abhorrent inhumane system would have been greeted with great anticipation and excitement

Douglass, a charismatic speaker and powerfully attractive man, had grown in confidence and inspired something close to devotion in women’s groups. The press noted that his good looks caused quite a flurry during his visit to Cork.

Despite the speculations, though, any rumours of misconduct were quelledby those close to him.

At another soiree held for Douglass a local bard Daniel Casey sang a ballad he composed in the visitor's honour, “Cead Mile Failte to the Stranger.” The chorus went – “Cead mile failte [A hundred thousand welcomes] to the stranger, free from bondage, chains and danger.” In response, Douglass was moved to sing an old abolition song.

Douglass felt a strong affection for Cork, a feeling reciprocated by the Cork Anti-Slavery Societies and symbolized by the gold signet ring which Cork’s Lord Mayor Dowden sent to Douglass on behalf of the city.

Douglass was very moved by this gift, stating it was the first piece of jewellery he had ever owned. In his thank-you letter he stressed his gratitude:

“I shall ever remember my visit with pleasure, and never shall I think of Cork without remembering that yourself and the kind friends just named constituted the source from whence flowed much of the light, life and warmth of humanity which I found in that good City . . . I shall wear this, and prize it [the signet ring] as the representative of the holy feelings with which you espoused and advocated my humble cause.”

Douglass left Ireland in January 1846 and continued through Scotland, Wales, and England, returning to America in April 1847 once his freedom had been bought from Hugh Auld by a group of women abolitionists in England for £150 (over $700 at the time).

Back home, although many Irish Americans opposed his civil rights efforts, Douglass viewed the Irish in America and Ireland as persecuted and drew parallels with Black people.

Personal Impressions and a Transformation

Douglass’s tour through Ireland left a lasting impression on him. The thinkers and debaters he met gave him a wider perspective on both his personal situation and abolitionism. Treatment as an equal for the first time proved a liberating experience and transformed the “autobiographical orator into a commenter on domestic and international issues.”

His time in Ireland was never forgotten and he held great affection for the country which provided him with the respect he yearned for in his native land. He expressed these feelings in a letter to Garrison the day he left Ireland:

“I can truly say, I have spent some of the happiest moments of my life since landing in this country. I seem to have undergone a transformation. I live a new life.”

It was during this tour that the great humanitarian Douglass was born. Back home he attended the world’s first Women’s Rights Convention in New York in 1848 and later campaigned for free public education, prison reform, and the abolition of capital punishment.

A lesser-known side of Frederick Douglass was his passion for music. According to Douglass, while in a music shop in Dublin, he asked the shop owner if he could try a violin. He was handed it with “seeming reluctance,” recalled Douglass. He quickly, however, won over the shop owner’s confidence with his accomplished renditions of Irish tunes.

Years later he taught his grandson, Joseph Douglass, to play that same violin. Joseph went on to become the first African American concert violinist.

Fifty years after his visit to Cork, Frederick Douglass died on February 20, 1895. On his right hand, he still wore the ring gifted from Cork, and Daniel Casey's handwritten ballad was found in pristine condition among his personal papers.

His death was reported globally, and many British and Irish newspapers printed long obituaries to the most famous African American to visit their shores.

Back home, an admiring obituary in The New York Times suggested that Douglass’s “white blood” accounted for his “superior intelligence.”

This suggestion would have angered Douglass especially as later in his life he learned that his mother had been the only Black person in Talbot County who could read, an amazing achievement at the time for a plantation worker, about which he declared:

“I am quite willing, and even happy, to attribute any love of letters I possess, and for which I have got — despite of prejudices — only too much credit, not to my admitted Anglo-Saxon paternity, but to the native genius of my sable, unprotected, and uncultivated mother — a woman who belonged to a race whose mental endowments it is, at present, fashionable to hold in disparagement and contempt.”

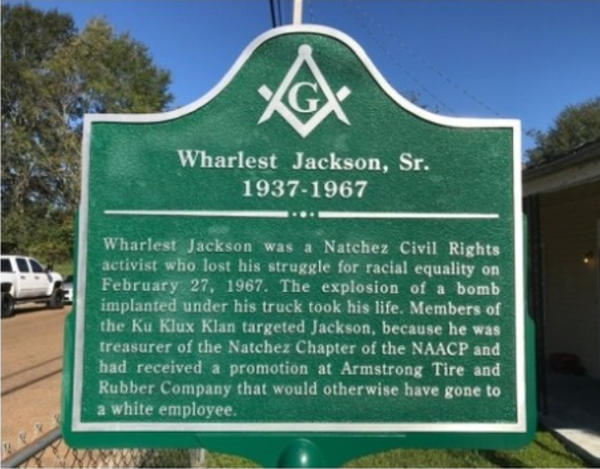

After his death, his reputation declined as did the general standing of African Americans which worsened in the ensuing period of the abhorrent Jim Crow Laws, a systemic strategy designed to subjugate and keep African Americans in their “rightful place.”

An Afterthought

I wonder what Frederick Douglass would have thought of Ireland if he were to visit today. Certainly, he would have received a warm welcome and his story applauded. He would, however, have had to listen to Irish people of colour voice their grievances at the increasing intolerance and racism in their communities. He would have had to condemn this, something which would have saddened him.

With increasing globalism and the pervasive influence of social media, people are becoming more intolerant, more selfish, and sadly less inclusive. We are shutting the gates. Ireland, like the rest of Europe, is experiencing increasing multi-culturalism and is, despite its welcoming nature, having to deal with rising intolerance towards non-nationalists and people of colour.

Ireland is, fortunately, one of the very few European countries where anti-migrant nationalist parties have no representation at the local or national level nor elected representatives . . . to date.

There are also some positives in a society where many people do not see colour as a hindrance to inclusion at the top level. Ireland’s former prime minister and current deputy prime minister, Leo Varadkar, is half Indian and gay. In 2019, Fionnghuala “Fig” O’Reilly was crowned Miss Universe Ireland, making history as the first woman of colour and Black woman to represent Ireland at the international competition. And this year, Pamela Uba was crowned the first Black Miss Ireland.

In October 2021, Dublin City Council unveiled a plaque honouring Fredrick Douglass for his immense contribution to human liberty and progress. In his speech, Councillor Mícheál Mac Donncha reminded us not only of the work of Douglass but also the continued need to oppose racism. “Further commemorations like this serve as a reminder that while enslavement was abolished in the United States, racism persists and needs to be opposed vigorously in all countries, including Ireland.”

In the spirit of Frederick Douglass, it is upon us to rise and re-activate his plea to “Agitate, Agitate, Agitate,” and turn the tide of intolerance and racism, and foster an anti-racist culture.

In fact, I would change the wording to “Educate, Educate, Agitate,” as Douglass in the 19th century believed education in the form of learning to read and write were “the pathway from slavery to freedom.”

Sources:

- Mulhall, Daniel. Frederick Douglass in Ireland, 1845-46. Fenton, Laurence. Frederick Douglass In Ireland: “The Black O’Connell”

- Jenkins, L. M. “Beyond the Pale: Frederick Douglass in Cork”

- Douglass, Frederick. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave

- Douglass, Frederick. My Bondage and My Freedom

More about Frederick Douglass and Sylvia Wohlfarth