Letter from the Editor: Representing

It’s been a crazy few weeks of late. Between the holidays and the meteoric rise of Omicron; the death of the iconic Betty White who—who knew?—was quietly engaging in acts of antiracism; the appropriateness of life without parole for Ahmaud Arbery’s murderers; and then the passing of the brilliant Sidney Poitier—a huge loss even if expected at 94.

While there was much rejoicing over the sentencing of Arbery’s killers, the whole situation saddens me. They may have gotten what they deserved, but Arbery certainly did not and I’ll take the sound of his mother’s voice to my own grave. And, as an avid runner myself, the scariness and insanity of it all plays over and over in my head. Those of us who are both runners and women have our own set of fears, but Arbery’s murder is above and beyond.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about “representing,” which is certainly not a new concept, but one I thought we’d have made at least a little progress on by now (if not on racism itself). I first studied it over thirty years ago, and I’m sure it wasn’t remotely new then.

I imagine all our Black readers know the concept, and probably the term. For our white readers, however, who might or might not know what it means, “representing” is when you’re the only Black person or other Person of Color in the room (team | school | neighborhood | company | town) amidst a sea of expectant white faces.

Oftentimes, sadly, you might be one of the few Black people a lot of those white people have ever talked to in a peer setting, and you know—we all know—that a lot of them are biased. Maybe all they know is what they’ve heard in the media, and the media says nothing nice about anyone. And so you feel the need to represent your race in the best possible light, suppressing those parts of your personality that might be considered stereotypical; bottling up your opinions and even sometimes anger, lest it be seen as representative; ignoring the Karens that seem to be everywhere; and even picking and choosing what you wear and what you eat and how you do your hair to avoid racist assumptions.

Think about that. A lot of us, regardless of race, are not super comfortable meeting new people under the best of circumstances. Certainly not us introverts, but many others, as well. In a lot of settings, we all feel pressure to present ourselves in the best way possible. We’re keeping up with the Joneses, we are in fact smart enough to be in the honors class, we deserve the job we’ve been hired to do. But never, ever, in a billion years, have we white folks had to layer into all our situational insecurities a concern that we need to be on our best behavior as “white people.” That everyone else in the room will develop opinions about “all white people” based on our words and actions. I mean, let’s be honest: we don’t think about being white at all, except to other “others.”

We don’t think about it because we don’t have to. As the majority, our race just fades into the woodwork and we assume we’re being judged as individuals (or possibly by other demographics, but we all know enough people of other genders, ages, etc. that we don’t “represent”). But consider how it must feel to carry the weight of millions of people on your shoulders.

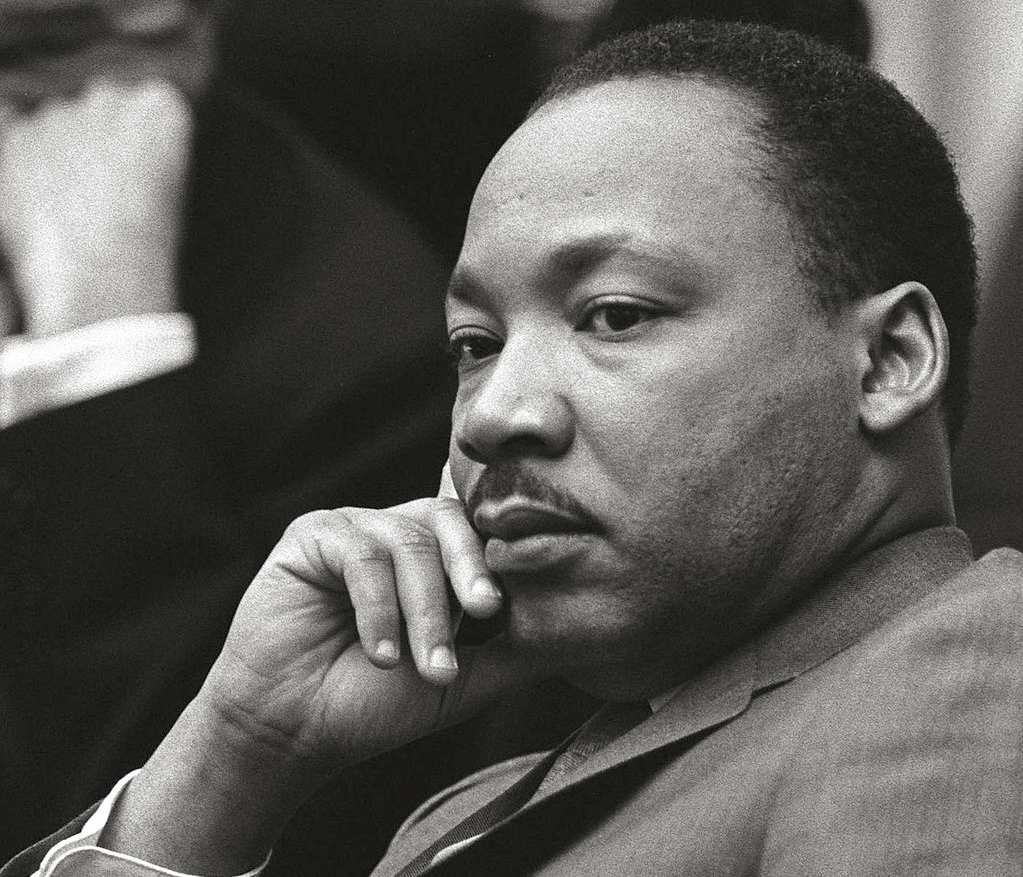

Although I was thinking about this topic before Sidney Poitier passed away, he is an excellent example of representation, and it was something he thought a lot about as one of the first major Black actors. As he noted, “I was the only Black person on the set. It was unusual for me to be in a circumstance in which every move I made was tantamount to representation of eighteen million people.”And, he felt “as if I were representing fifteen, eighteen million people with every move I made.”

In particular, it shaped his film and character selections. “It’s a choice, a clear choice,” Mr. Poitier said of his film parts in a 1967 interview, according to The New York Times. “If the fabric of the society were different, I would scream to high heaven to play villains and to deal with different images of Negro life that would be more dimensional. But I’ll be damned if I do that at this stage of the game.”

If you can imagine the pressure of representing to a couple of people or, worse yet, an entire room, can you imagine the stress of appearing on the silver screen to millions? In his autobiography, The Measure of a Man, Poitier says, “I’ve learned that I must find positive outlets for anger or it will destroy me. There is a certain anger: it reaches such intensity that to express it fully would require homicidal rage—self-destructive, destroy the world rage—and its flame burns because the world is so unjust. I have to try to find a way to channel that anger to the positive, and the highest positive is forgiveness.”

Other times, he let the anger out. “Okay listen, you think I’m so inconsequential? Then try this on for size. All those who see unworthiness when they look at me and are given thereby to denying me value—to you I say, I’m not talking about being AS GOOD as you. I hereby declare myself BETTER than you.”

No one—no one—should be responsible for upholding the image of other people, let alone millions, an entire race. Although to some the height of Poitier’s fame was a while ago, the issue continues—I heard Gabrielle Union discuss it just a couple of days ago, and I’ve had friends share their discomfort. Although representing isn’t the worst effect of racism, it’s an onerous burden few of us white folks can even imagine. Yet Poitier did it with grace and dignity, earning an Academy Award along the way. Rest well, Mr. Poitier. As great as you were, your best role was your own.

Love one another.

Sherry Kappel

OHF Weekly Managing Editor

The Clay Rivers Interview

OHF Weekly editor-in-chief Clay Rivers on the stumbling blocks to leaving race-based prejudice behind, ways to remove them, and the throughline to his writing.

OHF Weekly In four sentences, how would you tell us you’re on Team Racial Equity without saying you’re on Team Racial Equity?

Clay Rivers Before we get started, do you think you guys can get me an espresso?

OHF Weekly I . . . uh . . . maybe afterwards.

Clay Great. 1) Once you see someone as human, you can never unsee their humanity; 2) Regardless of ethnicity, gender, age, sexual orientation, political or religious affiliation (or the lack thereof), or physical ability, we all want the same things: to be accepted, understood, and loved; 3) We are more alike, my friends, than we are unalike—thank you, Maya Angelou; and 4) love one another—thank you, Jesus.

OHF Weekly What was the moment you decided to write and publish your works for the world to read?

Clay I’ve had several moments when I decided to write and publish my works for the world to read. I started keeping journals in middle school and wrote down all the typical angsty stuff teenagers go through, but everything I wrote was for private reflection, not public viewing. While working on my memoir, I combed those old journals for details, and thank God no one else got to read them. They were dreadful. But I continued journaling well into my forties.

I’ve been a “creative”—an actor in stage, television, and film; and as an graphic designer and art director since I was in second grade—so “putting myself out there” was nothing new to me. But publishing works seems different for some reason. Other forms of creative expression are collaborative endeavors. Rarely is a stage play, TV show, film, piece of merchandise, or product the work of a single person. Several people are involved in the process. But the responsibility for a published indie work is the sole responsibility of the writer.

And for that reason, writing and publishing anything of my own always wrings out a bit of my anxiety. Even with the input of editors, readers look to the writer as the sole source for literary works. Will people interpret what I’m saying the way I intend? Am I being clear? Will my words inspire or incite? Does what I write even matter? Are people even reading this stuff? Any combination of these questions go through my mind to varying degrees with everything I write.

The first time I decided to write for someone other than myself was in 2007 and had nothing to do with racism. I had recently moved back to Orlando after living in L.A. for nine years. One evening while parked on the couch channel surfing, I came across one of VH1’s Behind the Music rockumentaries. You know, the ones where they tell what went on in the featured artist’s private life while they were making hits the world loved.

That night, Behind the Music focused on Billy Joel. As the show covered his public rise to fame, it also told of personal highs and lows. Slowly but surely I came to notice something: most of Joel’s best-loved songs were tied inextricably to very personal events in his life. The songs I had been singing weren’t casual musings; they were songs from the soundtrack of his own life.

By the end of the show, tears streamed down my face. I had an epiphany that shook me to my core. I knew I was an artist and understood that art was an authentic expression of emotion and life experience. That was part and parcel of what made Billy Joel so popular: people identified with the messages in his songs . . . not to mention his talent. I found myself telling God that I wanted him to use my talents and to send me someone who would help me with my writing. And I forgot about it.

Long story short, an old friend I hadn’t seen for ten years referred me to her writing coach. And coming back from L.A., what did I want to write? Screenplays. Just as the industry’s interest in the genre came to a grinding halt. I wrote a couple of scripts, got a couple of awards in national competitions, and that was really about it.

Then there was answering “the call” to write my memoir. That’s a whole ’nother story I’ll tell at another time.

The decision to put it all out there in terms of writing about racism came a few years after the murder of Trayvon Martin and that spate of horrific events. I’d been having conversations about race in America with a number of my white male friends but found I was having the same dialog over and over again. I decided to write my thoughts down in an essay and post it online for people to read. Any reservations about putting my work out there evaporated when once that essay, “How I Talk to White People About Racism,” was posted. It was pretty popular. People were clicking on it, reading it, and responding. The New York Times even picked it up for their Conversation on Race series.

More than anything else, the fact that people seemed to find value in my point of view on race, personal growth, and politics as a forty-eight-inch tall, Black, Christian, gay man was the biggest motivator in continuing to write.

OHF Weekly In your opinion, what’s the biggest obstacle to people changing their race-based thinking and actions for a more equitable worldview?

Clay I’d have to say there’s a trio of obstacles that stops some folks: apathy/fear, doubt, and ignorance.

A lot of people are perfectly fine steeping in their race-based prejudice. In order for them to step out of their hatred hot tub, they first have to admit the hot tub water is cold. By that, I mean they have to realize their current belief system either no longer serves their best interest, is outdated, or is untrue. But some people have held a death grip on their belief system for so long they can’t imagine living any other way and have no interest in changing their way of thinking.

What would their family and friends say? Who would they be if they weren’t hating Black, Indigenous, and People of Color? They’d have to admit that their way of thinking is incorrect. And we all know, it takes a fair amount of introspection and fortitude for anyone to look at their choices and acknowledge to themselves that they are problematic. It’s their identity and the idea of being anything other than a raging ball of hate is unthinkable. It’s unimaginable.

Some folks know the hate they’ve been taught doesn’t match up with what they’ve experienced with Black, Indigenous, and People of Color. They know the hate they’ve been indoctrinated with is wrong. They’ve been nice to People of Color or may even have “a” friend of color or two, and they desperately want to change. But the reason they can’t make the jump is because they don’t believe change is possible.

And there are other people who want to change, but they don’t know how. They simply have no idea where to begin. So they fall back on patterns of racist behavior that are familiar.

But I’m a firm believer that people can change when they want to change, when they know change is possible, and when they know how to change. I know it’s possible because I’ve seen it happen. Too many times for it to be considered a fluke.

OHF Weekly To write about racism, racial inequity, oppression, and the like, writers have to dig deep into a disconcerting reality, sometimes that involves self examination. What’s been your most revealing article and why?

Clay My personal favorite? “If Not Now, White Folks, When?” Some writers specialize in the historic aspects of racism, some focus on the legal ramifications, and others focus on the political dimensions. Me? I write about the interpersonal aspects.

“If Not Now” was written for consideration in the Chicago Quarterly Review as part of an annual anthology. They wanted the thoughts of Black writers, so I took that as an invitation to share what it’s like, for me as a Black man, to watch white people come to grips with racism. The delivery was intended to be similar to that of a stand-up comic. You know, a mash-up of uncanny observations, genuine frustration, and faux outrage. Despite not making the cut, I still feel it’s a fine bit of writing. It didn’t make the cut so I guess it didn’t stick the landing.

I tried to express my frustration, anger, and disbelief about how slow some white folks can be in realizing that the elephant in the room is indeed the elephant in the room. Yes, this thing you’re seeing is indeed the thing you’re seeing. This behavior is called “this.” And yes, you do this. Regularly. What do you mean, ‘Why didn’t I tell you sooner?’ You wouldn’t have believed me if I told you sooner. You can barely believe the words coming out of my mouth right now. Why should I think you would have believed me earlier?

I have to laugh at people’s reactions to some of my articles. They often say You’re so patient the way you explain things to people. If they heard me read some of my own writing, I'm sure they’d get an entirely different impression of my “patience.”

That stuff isn’t pretty, but then, neither is racism. Marley K., Catherine Pugh, and a host of other anti-racism writers frame racism as abuse. And the similarities cannot be missed. The racism Black people endure in America is nothing short of abuse. Black people live with a lot of suppressed pain and trauma. What’s pretty about that? The deepest wounds are the ones you can’t see.

OHF Weekly What is the one thing, one principle, you’d like for your readers to take with them from your body of work on racial equity and why?

Clay This brings us right back to where we started. I hope people come to realize that anti-racism and allyship are not rocket science. The concept is insanely simple, but not necessarily easy. It’s about intentionally choosing to be the best person you can be at any given moment and having love as your guiding force and motivation instead of hate. Sometimes that means putting the needs of others ahead of your own. A lot of the time it means practicing active listening instead of running your mouth. In the beginning, these are difficult choices to make, but with practice, like anything else, they feel more natural with time.

It’s a heck of a lot easier to treat someone with respect and care when you understand that the thing you share in common with someone who looks, lives, or loves differently than you is your humanity. Science has proven that 99% of human DNA is the same. Humans cannot be divided into sub-categories. There is no such thing as race. It’s a social construct, just like Santa Claus and his flying reindeer. The throughline of all my articles can be boiled down to three words: love one another.

OHF Weekly With all that’s going on in the world, why do you still write about racial equity, allyship, and inclusion?

Clay Somebody has to. Why not me?

OHF Weekly Clay, thanks for your time.

Clay No problem. Somebody promised me a latte. When do I get my latte?

Photos courtesy of Clay Rivers.

The Clay Rivers Short List

Want to read more works by OHF Weekly writer Clay Rivers? We’ve got you covered. Here are three of our favorite articles.

New This Week

Subscribe

Subscribe for free email delivery of OHF Weekly and articles that have established us as a valuable and accessible resource for people interested in racial equity, allyship, and inclusion. Don’t miss out. Sign up now!

Final Thoughts

Love one another.

Top photo by Lucas Gouvêa on Unsplash

OHF Weekly Founder and Editor-in-Chief, Clay Rivers. Photo courtesy of Clay Rivers

Member discussion