Letter from the Editor

Writing about Black History Month can be a little stressful. So many deserving individuals to highlight, so many important events, more people sitting up and finally paying attention.

White people and white companies continue to trot out Martin Luther King, Jr. and his dream—a beautiful man with a beautiful dream, to be sure—but ignore the other parts of his messaging, or that his dream is still far from reality. They showcase the same inventors and historic figures as the year before, cheer for their accomplishments, and continue to gloss over the struggles they faced.

People who haven’t commented all year are suddenly woke. I’m glad they’re supporting the right side of history, don’t get me wrong, but so much more is needed. Some take on political issues, which is great for those who stick with it after February, and still others highlight Black businesses, which I love (especially those like Target who do it all year).

When Clay used a picture of gymnast Simone Biles to open up the month, it got me thinking a lot about athletes—Black athletes, of course, and their dazzling successes across a wide array of sports, but also the continued adversity.

At sixty, I’m old enough to remember a bit of history, a lot of change, and a lot of failure to change.

Although Fritz Pollard played in a young NFL in the 1920s, the owners quietly agreed to re-segregate until opening the league back up in 1946. The famous Jackie Robinson, as many people know, broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball in 1947. Nat Clifton was the first Black basketball player to join the NBA in 1950. Black tennis players also broke through in the 1950s, with Althea Gibson notably being the first Black woman to win international tournaments, followed by the incomparable Arthur Ashe a few years later. The first Black NHL player—actually Canadian—didn’t take the ice till 1958. Muhammad Ali, a civil rights icon, became a professional boxer in 1960, the year before I was born.

Sixty is not very old in the grand scheme of things, and all these firsts were within fifteen years of my birth. By the time I could remember watching sports as a child, there were already quite a few Black players excelling in the NFL, NBA, and MLB; while many would laud that pace of change, it doesn’t tell the entire story. I also remember that all the quarterbacks were white back then, and hearing that “the Black players aren’t smart enough,” among other ludicrous things.

Although those kinds of statements have been disproven many times over (I have an extra soft spot for Russell Wilson as a former NC State player!), there is still a significant shortage of Black coaches, general managers, and owners—i.e., the positions of real power.

Former Dolphins coach Brian Flores is suing the NFL for racism even as I write. Every single sports aficionado can cite numerous examples of coaches, teammates, owners, and others caught using the N-word. Far too many press conferences stating, “I’m sorry . . . but I am not a racist.” And still, Colin Kaepernick is sidelined while inferior quarterbacks play on.

The NHL never fails to amuse and bemuse me every year with their celebrations of Black History Month while a mere three percent of pro hockey players are any color other than white and the handful who are Black are almost all Canadian. (Lest anyone think Canada is all that better, however, one need look no further than Indigenous Carolina Hurricanes player Ethan Bear, who has spoken out on multiple occasions about the racism he dealt with while playing for Edmonton.)

Althea Gibson notwithstanding, women in general—and Black women in particular—have lagged behind men in public support of their athleticism. Title IX wasn’t signed into law until 1972, when I was almost a teen, and still hasn’t erased the discrimination across virtually all sports in the US, let alone around the world. French skater Surya Bonaly, US gymnast Gabby Douglas, and Japanese tennis player Naomi Osaka, all Black, have each dealt with racism and undue scrutiny of their backgrounds, their lives, their clothing, and even their hair—as have Biles and tennis great Serena Williams, despite being quite possibly the best athletes ever, of any gender or color.

It’s not the athletes themselves or the leagues, however, interesting though they are. It’s that sports are a vivid, obvious, inflated in-your-face microcosm of the rest of America. We all saw Kaepernick take a knee, heard the names that Williams has been called, watched the world-wide response to Biles’ mental health issues. We know the history, which has taken place in a very public arena. We can see quite clearly how amazing these athletes are and the racism they’ve had to deal with in the public eye. White folks can deny redlining in other parts of the country; we can twist the stats, pretend that Black men deserve more and longer jail sentences, and chalk it all up to “identity politics”; but it’s impossible to unsee the overt racism in the wide world of sports.

Which brings me to my real issue with Black History Month. Just as the challenges Black athletes face are representative of those Black people face across America, Black history is an integral part of American history. Just as there’s no such thing as race beyond social constructs designed to hurt fellow human beings, there is no such thing as a unique “white” or “Black” history.

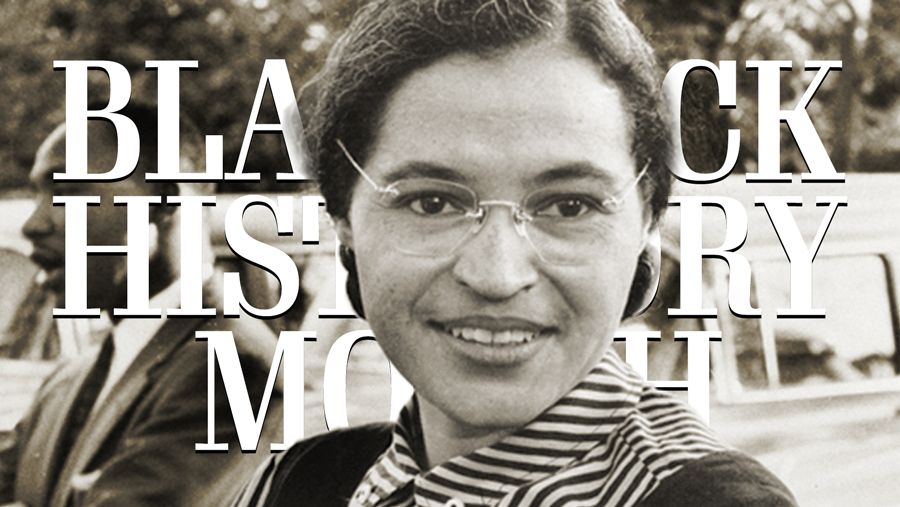

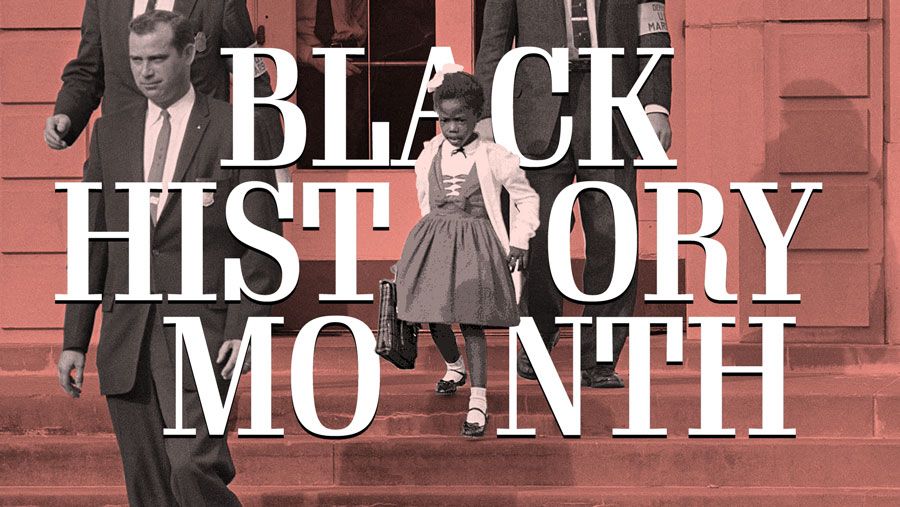

While celebrating Black History Month pays tribute to some wonderful people who deserve to be recognized, that celebration also continues to treat them as somehow separate or “other.” Worse, it creates a “safe space” between white people looking on, versus historic white figures. We see Rosa in the back of the bus, but the picture is cropped and we don’t have to relate to those who put her there.

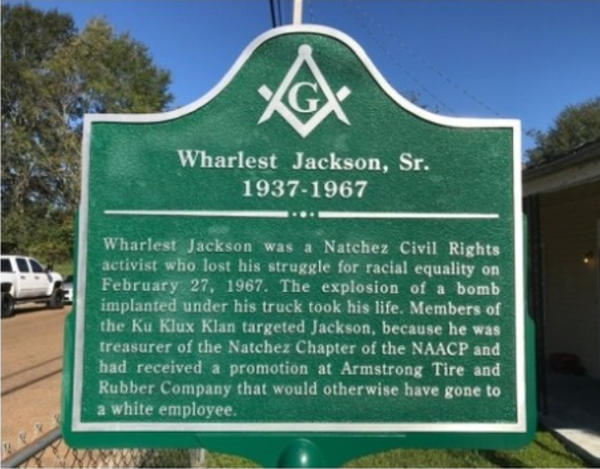

Black history in the US is American history—period. There is no defining whiteness here without the context of Blackness and vice versa, for better or for worse. White folks have committed a lot of atrocities against our fellow human beings over the years and continue to commit them—we can’t ignore those actions by having a white history wrapped in obfuscation and pretty bows along with a carefully curated Black history that we trot out once a year to make white people feel better.

We can’t say no to Critical Race Theory because it combines the two and makes white folks uncomfortable. History is what it is.

I’m not advocating that we ignore George Washington Carver or Ida B. Wells, or Martin, Malcolm, Zora, or Toni next February. I’m saying that we can only fully understand and appreciate Carver, Wells, Hurston, et al. in the context of the times they lived in, the oppression they dealt with, how it shaped who they were, and how it’s shaped the rest of us. They were not just great, they were exceptional in light of their circumstances. So appreciate them. Put them on a pedestal. Because they weren’t just great Black people, they were great Americans and great people.

Love one another.

Sherry Kappel

OHF Weekly Managing Editor

This Is Why We Celebrate Hip Hop

By Jesse Wilson

Despite Black people’s rich history and diversity, the most prominent touchpoint to those unfamiliar with Black culture is often our achievements in sports and entertainment.

Consequently, many truths go untold and large sections of our society continue to live unaware of the many cultural achievements that define our lives and experiences today.

The triumphs and accomplishments are not exhaustively taught and celebrated, but you need only to lift the veneer of mainstream media and historical information to see a rich history of where People of Colour have contributed many of the scientific and economic developments, as well as the political breakthroughs that we benefit from today.

In some ways, the continued suppression of the truth to suit the false narrative of supremacy and dominance seems tragic, if not comical. It is like playing Whack-a-mole: in attempting to rid your lawn of garden moles, you find that as fast as you remove one molehill, another one appears, sometimes bigger.

So let’s play this game and take on the attempts to suppress or denigrate a music genre and culture. I don’t need to go into the actions taken to silence Hip Hop at the time of its emergence or address the commonly held view that it was a fad and would never last. We might remember that ever since Hip Hop’s inception, the main focus of criticism has been on the negativity that it represents. But today, forty-plus years later, the music and culture are still here and thriving.

Before I continue, let me clarify the gaping difference between Hip Hop and Rap. In simple terms, Hip Hop is a culture comprising four elements: DJ-ing, MC-ing, breakdance, and graffiti. Rap, which we know today as spoken word delivered over a beat with rhythm and rhyme, is a genre of music that grew out of Hip Hop. Its origins go far further back, to the oral traditions of West African poets and griots who served as storytellers, advisors, social commentators, and diplomats. For the purposes of this essay, I’ll refer to the culture and the music together as Hip Hop. They both exist because of each other—Hip Hop with its founding philosophies and Rap, once an oral tradition and now a highly commercialised commodity.

Admittedly, some aspects of Hip Hop need to be called out for promoting violence, misogyny, racism, and homophobia. I am by no means advocating or suggesting any of that is a good thing and should be encouraged. Instead, I want to shine a light on how talented artists, primarily People of Colour, and the whole Hip Hop genre have not been given their due for their creativity and positive influence.

There is a reason why Hip Hop and the associated culture are an easy target for mainstream media to label and describe as all that is socially wrong: together they threaten the dominant parts of society and systems that keep people in place. Focusing only on negative stories provides the perfect cloak and justification for disregarding and disenfranchising large sections of the community. So while we are busy recoiling from the symptoms, our focus is redirected from the cause.

Like most things in life, there is always another side to a story; social issues do not occur in a vacuum. There is always a reason why people behave and act in a certain way. If you want to feel the pulse of any era in history, you only have to look at the material produced by creatives of the time. In there, you will find rich pickings from poets, writers, and musicians telling the stories of people, the choices they had to make, and the ensuing consequences.

Yes, we urge to merge, we live for the love of our people

The hope: they get along (Yeah, so we did a song)

Getting the point to our brothers and sisters

Who don't know the time (Boyyyee, so we wrote a rhyme)

Instead in your head, you know, our job

To build and collect ourselves with intellect (Come on)

To revolve, to evolve to self-respect

’Cause we got to keep ourselves in check

Or else it’s . . .

[Chorus]

Self destruction, you’re headed for self destruction

Self destruction, you’re headed for self destruction

—Lyrics: “Self Destruction,” KRS-One, MC Delite, Kool Moe Dee, MC Lyte, Daddy-O & Wise, D-Nice, Ms. Melodie, Doug E. Fresh, Just-Ice, Heavy D, Fruitkwan, Chuck D & Flavor Flav

Cultures evolve to reflect society, and perhaps that is why, despite the many people who see only the negative aspects of Hip Hop, many more appreciate the music form for what it is and has brought to their lives.

I remember my first exposure to Hip Hop in the early eighties—1982 to be exact. It was entirely by accident: I was sitting in the family living room eagerly waiting for the weekly broadcast of the popular Top of the Pops television show. For many years until its demise in 2006, this show listed the top forty songs in the UK charts, playing a selection with either a live performance or video of the artist or band.

On this particular Thursday evening, unexpectedly, a video and sound I had not heard before blasted through our television. I was immediately mesmerised. I had never heard, let alone seen, a record scratched, words repeated on a loop, graffiti artists spray-painting the side of a building, or young people body popping and locking. It was a crazy explosion of something fresh and different. I had no idea what I was looking at, and because it was so radical, I wasn’t sure if I liked it. Still, I remember how Malcolm McLaren’s “Buffalo Gals” had caught my attention of something different, expressive, and new on the horizon.

Fast forward a few years, and a fresh-faced fourteen- or fifteen-year-old stood in the middle of his first live concert watching, singing, and dancing to “Walk This Way,” the collaboration between RUN DMC and Aerosmith—and it was awesome! It was not long before I was paying attention to several emerging and established artists such as LL Cool J, Grand Master Flash, Sugar Hill Gang, Salt-N-Pepa—basically anyone with a prominent Black influence.

Naturally, my tastes expanded to consume a compelling underground message of resistance, enlightenment, and kinship. I found myself listening to artists such as KRS-One (“My Philosophy”), Public Enemy (“Fight The Power”), Eric B. & Rakim (“Ain’t No Joke”), and Afrika Bambaataa & The Soulsonic Force (“Planet Rock”) to name a few. Despite living on the other side of the Atlantic, their hard-hitting and culture-conscious lyrics made me think about my own experiences and the world I lived in.

That is the power of art and music: it transcends borders and speaks to both the heart and mind. Hip Hop is just one of many genres of Black origin that have shown how we can unite and derive entertainment, unity, messages on survival, and an understanding of love at many levels.

I could write a whole separate factual commentary on how Black music and music for People of Colour have shown our creativity and evolved from their original forms out of Africa to its various present-day incarnations, each time adapting to serve different purposes for the incumbent generation.

Instead, I want to focus on one enlightening positive message Hip Hop gave during the late ’80s. It came at a time when gang violence, drugs, police brutality, and more were ravaging communities. The government and the institutions you would expect to respond to the aforementioned social issues fell dramatically short and perhaps in some instances instigated and even perpetuated the circumstances. It took the Black communities who understood their culture to come together and spread the message of love, peace, unity, and knowledge of self.

Socially conscious Rap and its closely aligned cousin political Hip Hop existed with the purposes to educate, inspire, and foster radical social change, ao much so that the uplifting messages spilled out across the globe for all who cared not only to listen but to hear.

How We gonna make the Black Nation rise?

We gotta agitate, educate and organize!

—Lyrics: “How We Gonna Make the Black Nation Rise,” Brother D

Hip Hop cannot be denied its seismic cultural shifts, particularly how it unified DJ-ing, MC-ing, breakdance, and graffiti. It would take yet another essay to explain the origins that started long before I became aware of the phenomenon, but suffice it to say that Hip Hop has deep roots in Black history. Like any cultural movement that taps into a collective consciousness, it cannot be suppressed and contained.

For all its controversies, Hip Hop has continued to evolve and demonstrate time and time again that if you want to see community or see Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s America, what better place than within Hip Hop itself. If you are audacious and good enough, you will be judged by your character and ability, not by your skin colour.

“Became a slave to master self, a rich man is one with knowledge, happiness, and his health.”

–Lyrics: “G.O.D. (Gaining One’s Definition),” Common

It seems ironic that as I write this, Hip Hop finally received acknowledgement for its achievements on the world stage. For the first time in National Football League history, a Hip Hop Super Bowl halftime show featuring Dr. Dre, Snoop Dogg, Eminem, Mary J. Blige, Kendrick Lamar, and 50 Cent aired. The show opened with perhaps a telling song entitled, “The Next Episode.” Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg led a cast of Hip Hop giants to deliver a near fourteen-minute spectacular of Hip Hop hits from the last thirty years.

For many, seeing and hearing the music of their lifetime in the mainstream, in full view, set the stage for a momentous occasion not just because it was the first, but because it was a declaration of one of the most dominant music genres today, set in Los Angeles, the hometown of some of the performers and the winning LA Rams team.

But Hip Hop as we know has a long and divisive history and it is often used as a political tool. The Super Bowl performance was a first to be celebrated but in its wake cynicism emerged from both sides of the race debate and much consternation over the way the performers grabbed their crotches. Debates over Eminem taking the knee ensued, with talks of censorship, and all while multiple lawsuits against the NFL over racist practices still rage on.

Even so, a Hip Hop themed halftime show showcased an impressive history of performers while at the same time heightened awareness and discourse over past NFL practices and structural racism. It was not the time for Hip Hop to address the question of participation versus boycott, but the debate still simmers and boils, despite the NFL’s attempt to show anti-racist solidarity with visible slogans.

Hip hop connects with fundamental notions of identity and purpose, but it also influences the decisions young people make about their lives, lifestyles, and health.

—Dr. Raphael Travis, The Healing Power of Hip Hop (Intersections of Race, Ethnicity, and Culture)

As long as those with economic power continue to play Whack-a-mole by failing to acknowledge historic and present contributions from People of Color, more molehills will appear as people discover the truth for themselves and tell their own stories.

For those of you who look at Hip Hop with grave concern and question some of the lyrics, lifestyles, and messaging, consider this: A tremendous amount of the commercialised commodity that is Rap continues to be wrong, but history has proved and continues to prove that Hip Hop has had a positive influence. Like any group or demographic, you cannot lump the actions and behaviour of a few to be representative of all.

“Peace before everything, God before anything, love before anything, real before everything. Love power slay the hate.”

—Lyrics: Mos Def, “Priority”

More from our Black History Month series

More about and by Jesse Wilson

Giving to OHF Weekly

We published our first edition of OHF Weekly at this new location almost a year ago. Stepping out on our own, away from Medium, has proved to be the best move for us. We have no regrets and have learned a lot since then. One thing that has become very apparent is our dependence on the generosity of donors like you to keep the lights on. Because of your continued generosity, we’ll be able to defray some of our ongoing expenses like web hosting services.

So please, take a moment and make a one-time or monthly tax-deductible donation to Our Human Family. Thanks in advance for your support.

Final Thoughts

Top photo by Gordon Cowie on Unsplash

Member discussion