When I was asked to write a piece for a Black History Month series, my internal receptors instantly faced off in conflict. Surprised, appreciative, proud, but most of all, I felt bothered—uncomfortable, and over the weeks, it weighed on me as to how to address this topic. After the question was posed again, I agreed; although the uneasiness still existed, I felt that this was my opportunity to state my issue with this concept.

Coincidently, about the same time, I was also asked to be a part of a panel for Black History Month for a professional female audience who happened to be predominantly white, and I turned it down.

At this point, I had to put my bag down and unpack how I really felt about this month before I could write anything or even discuss the topic.

My unwillingness to take a seat on the panel or write an article had nothing to do with having anxiety about being front and center or an inability to write. I wasn’t even concerned about the material, as there is an abundance of worthy people and topics to write on; there are actually too many to consider and highlight, too many scholars, veterans, inventors, pioneers, fighters, and firsts to disregard, and most of all, too many unsung heroes for one writing inside one month.

Did Carter G. Woodson think about this in 1926: that in 2021 I would be asked to share my 54 years of 365 blackness inside 28 days? Considering it started as Negro History Week, linked to Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass’ birthdays, some may believe I should be satisfied that we get a whole month. Well, I am not.

Writing for Black History Month allowed me to drill down and figure out what was at the core of my disenchantment. When I thought about the month, I didn’t see it as a celebration. I questioned the sincerity, feeling that Black people have a small window to show the world our worth. Inside twenty-eight days, we have to share our rich culture and fortitude, and it had to be an exemplary tale of outstanding achievement. I felt as if we were still asking for approval to share our history, to prove our worth, and we are still asking for inclusion.

After asking myself why I felt this way, I realized that past experiences skewed my view. As I reflected on my disengagement, I realized my reluctance began in my youth observing my family, witnessing how hard my family worked to manage their existence while avoiding the topic of race. Rarely did we talk about our personal challenges of being Black; it surely wasn’t because we were free from ill-will. It was just something we did not give more energy than it deserved. Raised in a passive-aggressive household, we won small battles by getting ahead, despite our circumstances. We always have to prove we deserve mutual respect while working twice as hard and trying not to display contempt. To live this way is exhausting. It wasn’t until I was in college that I heard and met unapologetic Black folk who spoke openly about their hardship and African Americans’ plight, and I was in awe.

We always have to prove we deserve mutual respect while working twice as hard and trying not to display contempt

While I felt disdain for this annual ritual, I also understand the importance of utilizing any opportunity to lift and spread our rich history by educating all those willing to learn. I am proud of our heritage; I just don’t feel that it is right to have it confined to an imposed timeline. So, I have decided to draw outside of the lines by sharing our history, our contributions, our humanity, whenever and wherever I see fit.

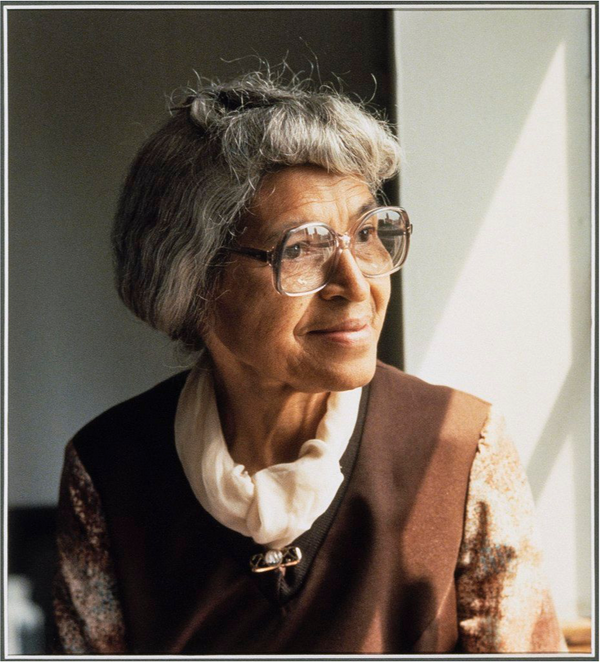

With that said, I present to you the father of Black History Month, Dr. Carter G. Woodson.

Born in New Canton, Virginia, in 1875, Dr. Woodson, the son of a former enslaved Black person, had to delay his education to work in the West Virginia coal mines. Despite his status, determined to continue his education, he graduated from Berea College and became an educator; he later gained his graduate degree from Chicago University and furthered his education at Harvard University, becoming the second African American to earn a Ph.D.

Dr. Carter G. Woodson’s life and contributions alone deserve more than a month. As a historian, he produced numerous literary works as early as 1915. He founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, with his A Century of Negro Migration: –1918, to his incomplete six-volume Encyclopedia Africana, which provided a look into a world that revealed the depths of Black people and even opened the eyes of African Americans, instilling pride.

As an educator capable beyond his position as Dean of Arts and Science at HBCU (historically Black college and university) beloved Howard University, Dr. Woodson continued to assess and assert that the education system lacked the sincerity to provide a complete inclusive reference.

While a progressive Civil Rights leader, it was said that Dr. Woodson was impatient with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and discontinued his affiliation due to conflicting views on how to move African Americans and the country forward.

Even though Dr. Woodson’s methods and documentation attracted colleagues and sponsors such as Marcus Garvey and W. E. B. Du Bois, some disagreed with his philosophy and attempted to ostracize and dissuade him. This, however, did not deter him, as he would continue his mission until his death.

Dr. Woodson bestowed a legacy for Black people that provoked thought and actions beyond his original intent. I recall experiencing my own enlightenment when discovering his works. My pseudo-relationship with Dr. Woodson’s legacy occurred during my college years, I was introduced to The Mis-Education of the Negro (1933), and I was captivated by its directness. This book became an unspoken right of passage for so many and is still read by many. It’s a read on society, Christianity, and control for those who seek an unabridged reference guide as well as for those who are in search of mental (racist) un-conditioning. We are still conditioned.

Dr. Woodson’s affinity for confronting society’s resentment of the poignant existence of Black people was a lifelong commitment. His works, influenced by America’s love-hate relationship with Black folks, addressed the destruction of the very thing we covet: our lives. Even worse was his reality check on the ways African Americans were incorporated into their predicament of self-destruction, which remains a hard pill to swallow.

Journalizing African Americans’ achievements, in an effort to validate and humanize, did not go without negative impact. There was retaliation, but Dr. Woodson would not be silent. There was always more to do and tell, as racial disparity and conflict waited in the shadows of the coming days, months, and years. 1919, Red Summer, and the devastating racial killings of more than 1,000 Black Americans did not sway Dr. Woodson’s mission. Rather, it encouraged him to double down on creating Negro History Week and controlling the works’ tone and authenticity by minimizing external views.

Darlene Clark Hine quotes Woodson as writing, “ . . . while the Association welcomes the cooperation of white scholars in certain projects . . . it also proceeds on the basis that its important objectives can be attained through Negro investigators who are in a position to develop certain aspects of the life and history of the race which cannot otherwise be treated. In the final analysis, this work must be done by Negroes . . . The point here is rather that Negroes have the advantage of being able to think black.” This statement did not sit well with some of his colleagues, some abandoning the mission. Nevertheless, Dr. Woodson continued to devote the rest of his life to collecting historical records and artifacts. 1926 pioneered the first Negro History Week to coincide with Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass’ Birthday.

Dr. Woodson proclaimed, “If a race has no history, it has no worthwhile tradition, it becomes a negligible factor in the thought of the world, and it stands in danger of being exterminated.”

Later, in 1970 Black United Students and Black educators at Kent State University broadened the concept by extending the week to a month, starting February 1, 1970.

During the celebration of the United States Bicentennial in 1976, President Gerald Ford recognized Black History Month.

Black History Month is also known as African American History. It was more than an important American milestone; it was pivotal to other countries’ acceptance and implementation, such as Canada, Netherlands, and United Kingdom.

Dr. Woodson proclaimed, “If a race has no history, it has no worthwhile tradition, it becomes a negligible factor in the thought of the world, and it stands in danger of being exterminated.”

If we forego the existential pursuit and focus on maintaining and celebrating a rich heritage, we do not need to seek approval and avoid the self-extermination Dr. Woodson speaks of.

It is critical that we not only pick up the torch from Dr. Woodson but lift it higher as we pass it on to the next generation. America must abandon the contempt and patronizing ways it interacts with various ethnicities. As we evolve, so should our means of telling the truth—the complete story, without calendar boundaries.

The month-long celebration of Black History does not negate America’s responsibility to accurately reference and regard African Americans as a valued element of American History. When we face and resolve this quest of fair reporting, we can realize the rich abundance of Dr. Carter G. Woodson’s legacy in its deserved totality.

We can share our history and our lives whenever we see fit, without approval or barriers. Although this is America’s issue, it is ultimately African Americans’ plight, and we must own the narrative; the good, bad, and the ugly—it is our responsibility. We do not own our history; we cannot afford to hold it back; it belongs to the world, it belongs to our future generations. Our legacy cannot be destroyed and must live forever.

In closing, to seek validation of one existence and humanity is demoralizing. Regarding others’ opinions as a hierarchy, succumbing to their pious views is an acceptance of an inferior role. This is what I initially felt about a one-month heritage recognition, and that did not sit right with me. Allowing someone else to determine when and how long I can celebrate who I am, is unacceptable. I realize that no one can control when and how long I may celebrate my heritage. Besides, I not only share the responsibility of keeping the torch lit, I must pass it on.

Originally published February 2021 in Our Human Family.

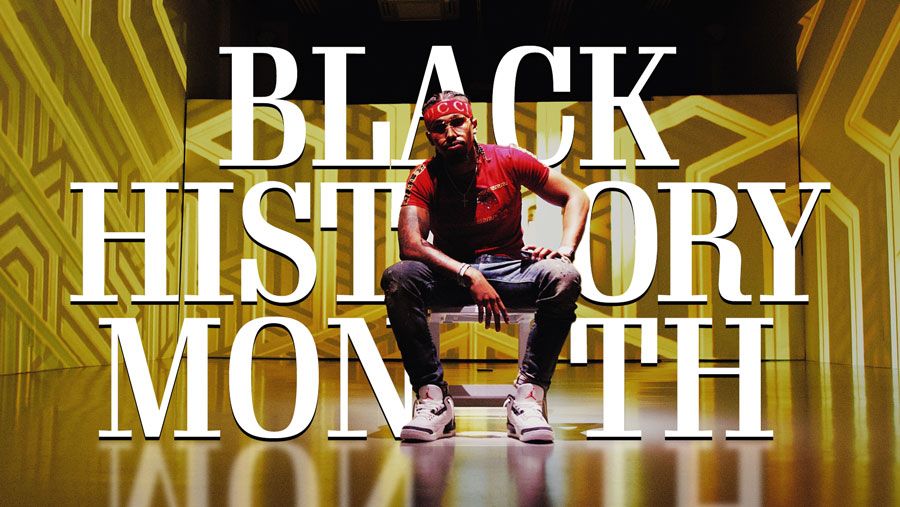

More from our Black History Month series

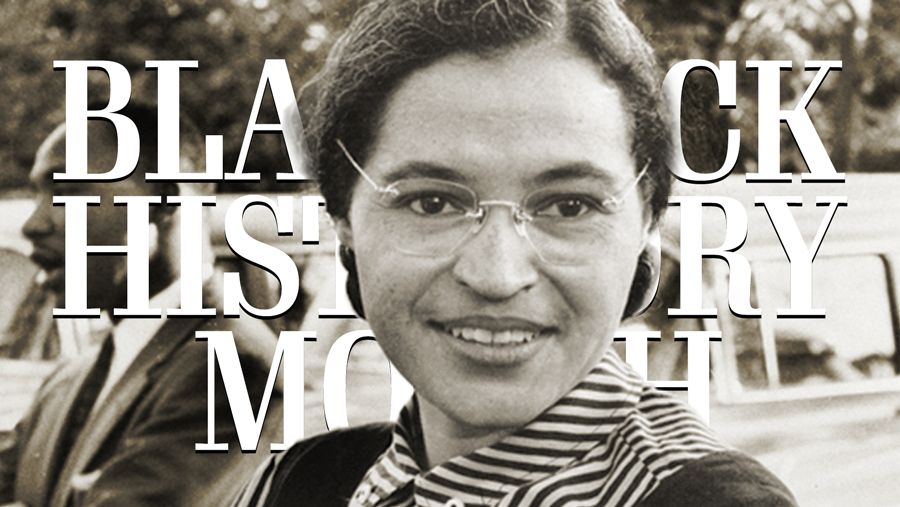

Top photo by Xan Griffin on Unsplash

Member discussion