Editor’s Letter

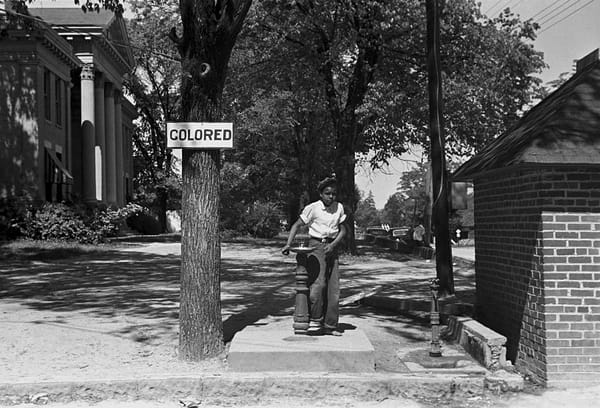

Black History Month is the time of year when we turn our attention back to our ancestors’ individual and collective accomplishments. When you think of our ignoble circumstances and sinister purpose behind our arrival to these shores in 1619, that we as a people are more than surviving yet less than thriving in America despite the incremental fulfillment of the Constitution’s guarantees is a testament to our fortitude, ingenuity, and character.

As some of you may know, my best friend, Mrs. Adams recently passed away at the incredible age of 103 years old. The world of 2024 surely would be almost unrecognizable to someone born in 1920 had they not experienced the monumental changes our country has wrought. My friend was front row and center for more than a century of it. Talk about some Black history.

A few years ago, Mrs. Adams agreed to be the subject of a biography, the primary focus of which was to share what it was like to live through times very much like these but still very much the same in terms of the need to maintain her dignity in the face of racism. And there was the whole matter of cultivating a positive outlook in a culture built to denigrate her. We sat down for a few interviews, but ultimately, we shelved the project as she began feeling apprehensive about putting so much of herself out there for the world to read.

As you can imagine, I felt disappointed not being able to share my friend’s wisdom with the world, but nonetheless, I respected her decision and shelved the project.

I’m not fond of funerals, homegoings, memorials, requiems, and the like. I avoid them so much that I’ve already told many of my friends chances are pretty high I will not be attending their interment. My stance is not out of disregard but self-preservation. Funerals take me in an emotional sense to a place I find inordinately tricky from which to escape (more than other people): the land of grief.

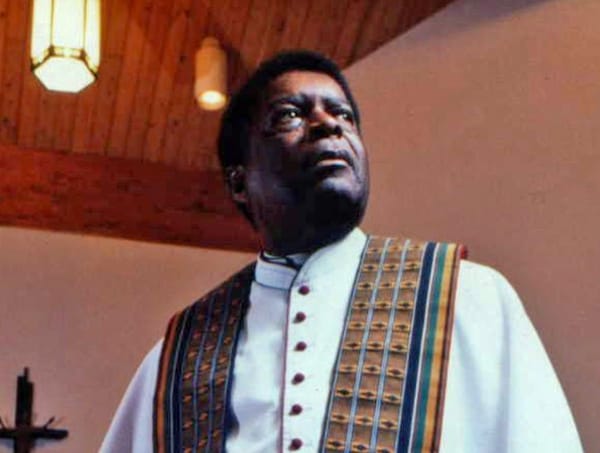

But I attended my bestie’s funeral.

Listening to the firsthand accounts of people I had only heard about via Mrs. Adams, I gained a fuller understanding of her story, how her seemingly mundane responses to situations and circumstances added up to millions of moments that altered the trajectory of an unknown number of lives. The end result and the way her family and friends’ lives were more intertwined than we even knew or imagined.

In one sense, it’s easy to assume capital H history consists only of incidents writ large on a local, national, or global scale. You know the happenings that impact humanity in life-changing ways; natural disasters, political upheavals, cultural movements, economic boons, and even gradual cultural shifts spanning large chunks of time. See William Spivey’s “Why Black History Month 2024 is the Most Important Ever” below for prime examples. More often than not, we only get a hint of the impact in hindsight.

But as my friend’s homegoing service demonstrated, Black history—both lowercase and capital H—occurs in our daily lives. As so deftly noted in R. Wayne Branch’s article “Are You Old, Daddy?”, parents’ response to racism and countless other -isms inform their children’s behavior. The murder of George Floyd rushes to mind. Were it not for the bystanders’ individual decisions to bear witness to the Minneapolis police officers’ crimes, Mr. Floyd would have been just another Black man getting “what he deserved.” There would have been no cell phone footage, not nearly enough questions, no public outcry for justice; no local, statewide, national, or worldwide outrage, no arrest, no trial, and definitely no conviction of Mr. Floyd’s killers.

An individual’s decision to tear down or build up, empathize or demonize, include or exclude may not seem like much at first glance. But collectively, they can grow to monumental proportions and change the world. Sometimes, we get to witness the fruit of our labor. Most times, we need to remember that we are more alike than we are unalike.

This is the work of love.

Love one another.

Clay Rivers

OHF Weekly Editor in Chief

Member discussion