Still to this day, the late 1980’s song First Time, sung by Robin Beck and featured in the Coca Cola advertisement, rings in my head. The instant I hear the song, I empathise with the emotion of firsts. First time, first love, oh what feeling is this. Electricity flows like the very first kiss, the song goes on to say.

The song reminds me how firsts tend to etch positive, indelible memories we eagerly recall in admiration. I know firsts are typically special because they often transform and bridge the gap from where we are into the unknown. It is for this reason they are remembered as defining moments shaping how we act and who we are.

But then, not all transformative firsts are equal. There are some, no matter how much we try to find the good and the positive, where we simply can’t because the associated memories are nestled in a nest of trauma with thorny sharp lessons. Nevertheless, these firsts bring with them a naked and acute realisation that a part of our lives and bodies are defined in not so much what we do but by the contrast of who we are.

I imagine if you ask any Person of Colour (POC) living in America, across Europe, or many parts of the world, they may share with reluctance recollections of their first and sadly inevitable racial encounter.

I guarantee whatever they say or do, the hurt and feelings are stitched into their very existence and remain a constant reminder that as much as we hear and see, the world today is better in many ways than it was yesterday. The changes didn’t come soon enough for the pain they endured.

I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.

—Maya Angelou

Racial Inequality Is on a Cycle of Rinse, Wash, Repeat

For many People of Colour, their skin colour’s significance is thrust upon them in an all-too-familiar, traumatising unwanted first. For me, my earliest racial encounter is rooted in school and came at a moment when my primary concern, like any other small child, was about fitting in and having fun. At the time, I was fortunate to be guided and supported by family. But here is the thing—no matter the support and family preparation, when this day comes, this first always cuts deep, leaving an everlasting echo that you grow up to hear in between the walls of communities, organisations, corporations, and government institutions.

The feeling of otherness once experienced comes with a recognition you cannot erase and ignore, you cannot climb out of when fatigued, and you cannot switch off and say I am tired and done. It is a tattoo or a form of branding that you may discover how to suppress but never fully hide.

Instead, you learn how to protect yourself, and as you recall pivotal global events surrounding the murder of George Floyd, you rightly become impatient but at the same time numb to the cycle of hope, promise, and despair. You know the energy it takes to momentarily believe the promise of change is consuming, so you remain guarded and never fully trust because what you see and experience every day is evidence of how the world operates on a repeated cycle of trauma and pain.

Is There Any Value in Asking When?

Whether you are a Person of Colour or not, when you first fully witness or rather, unfortunately, experience the repeated cycle of pain and suffering, it is only natural and human that you would ask, how long must this continue, how many more lives must be blighted by ignorance, how many more people must be made to feel less by the perpetuation of white supremacy? How many more people and generations must be made to feel that they must justify and fight for their right to be seen and treated as equal?

The questions keep coming, and I wish I could answer. I wish I could say something definitive like in one or two, maybe five or ten years, we will see an end to the continuation of racial inequality, but I can’t—and understandably, nobody honestly can.

Racial inequality feels like an open-ended fight where sadly not enough of us have tried to cauterise humanity’s self-inflicted wound. As a result, the wound is open, and despite the early signs of healing, the whole body is not aware, and so the true cost goes noticed, and the depth of the cut remains unknown.

I have concluded that there are many scholarly articles on why we face inequality today, and there have been many debates and discussions of what we need and should do next. But still, we can’t answer the question of when. We can’t provide a date when there will no longer be a need to celebrate the first black female president or prime minister because it is naturally expected.

Why is that?

Is it because those with power have no real desire for change? Is it because we need to unstitch hundreds of years of history and social change takes generations in the making? Is it because the extent of the problem is not fully understood? Again, many questions and so few answers, but please indulge me while I explain what I know below.

We Changed Our Laws but Did We Really Change?

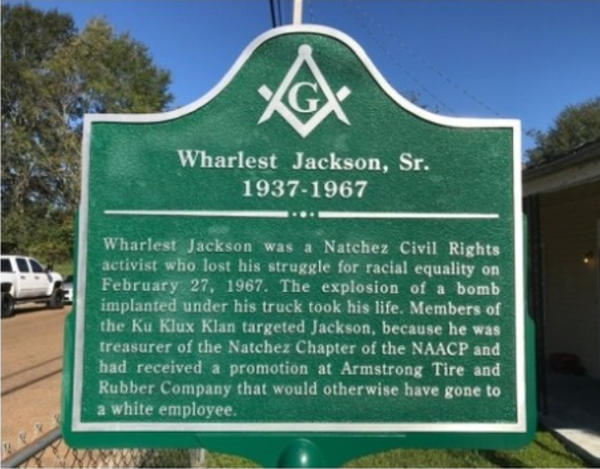

The United Kingdom Race Relations Act 1965 was the first legislation to outlaw racial discrimination. Before this date, in the United States, several civil rights acts came into place, namely the Civil Rights Act of 1957, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Civil Rights Act of 1968. With each act, the way that people were allowed to behave in public changed, paving the way for increased voters rights, removing segregation, and more. Each act was a landmark victory in our collective histories, tackling the behaviour of landlords, employers, schools, and companies. Since these initial acts, the United States, the United Kingdom, and the rest of the world have introduced further laws and legislation to better the lives of people discriminated against. But still, it has never been enough to change our societies; racial inequality remains.

Laws are merely a comfortable curtain around what we think and how we behave.

In part, it is no surprise inequality remains. What do laws do? Rules can and are often broken, and laws only tell us how we should act. I have often thought of the hard-won rights made possible by laws to be a minimum that makes life tolerable, but they are not, as some would believe, an end destination. Legislation alone does not change structures and systems and address culture. It does not address what’s needed to touch and change people’s hearts.

Eventually, there comes an acceptance

I know when I started writing this essay, I naively wanted to talk about changing hearts and illuminating privilege and power structures. But then it occurred to me who am I writing this article for. The people who need to read this probably won’t be because they are on a different path. But then you could argue this is why we write to share facts and opinions, thoughts, and ideas.

So I know part of me writes and hopes and part of me writes knowing the chances are if you have read this far, it is because you are interested and already versed in the knowledge that it is people who run our systems, institutions, and governments; people who make our laws; people who run the world we inhabit.

I like to imagine as a person who is reading about racial inequality, your knowledge and interest go beyond reading, and you have found a way to make a difference in your life and community because you understand changes in language, social habits, how we consume music, art, and literature, how we spend our money all contribute and define our culture. I like to imagine you are a person who embodies the change you wish to see and wholeheartedly believes that when people devote their time and energy to take an anti-racist stance, then a change in culture happens.

Be the change you want to see in the world.

—Mahatma Gandhi

So for that reason, I know I don’t need to write and talk about how we see and treat each other as humans or write about changing hearts and power structures because it would be preaching to the choir.

Instead, I will say despite the despair and longing for a better, fairer world, there comes a generational acceptance that the best I can do now is live, and live in the knowledge that I may not survive to see the promised land, but I know my role and responsibility is to hold and pass the baton so that the generations after me will experience a different and much better first.