It wasn’t all that long ago it seemed democracy and justice were on the march around the world. Since 1989, when the Soviet Union fell, dramatically illustrated by the crowds dancing on the ruins of the Berlin Wall and tanks turning against the overlords in Moscow, it seemed that power really was shifting to the people. Our existential opponent, Soviet communism, was defeated; the ideology of freedom and democracy had won. There was even a popular song at the time by the band Jesus Jones with the lyrics “right here, right now, watching the world wake up from history.”

It wasn’t all hype. As one dictatorship after another fell, the new governments pledged a commitment to free and fair elections, as well as the other institutions of democracy. According to the international research organization Freedom House, the number of countries it rated as “not free” fell to an all-time low of thirty-eight in 1992. It was an exciting time.

We worried, of course, about these newer democracies. Countries such as Russia and Hungary had not yet developed the robust democratic institutions and traditions that protected American democracy. It’s one thing to write a constitution on paper, but to turn it into a living breathing document that governs society is an entirely different thing. New York Timescolumnist and Nobel prize winning economist Paul Krugman remembered a friend of his, an international relations expert, making a joke during that time: “Now that Eastern Europe is free from the alien ideology of Communism, it can return to its true historical path – fascism.”

The sad reality of hindsight is we know what happened. Once promising democracies such as Russia, Hungary, Venezuela, Turkey, and India have devolved into authoritarian dictatorships. Even though they may retain many of the institutions that symbolize democracy, those institutions have been weakened, co-opted by the powerful to keep them in power. Although the elites are always the minority, they manage to maintain their privilege through tried-and-true manipulations by giving some small benefits to one group while turning that group against others. They scare the group to whom they have shared scraps from their bountiful table by warning them that these other, lesser groups can displace them as the recipients of these benefits.

Although the elites are always the minority, they manage to maintain their privilege through tried-and-true manipulations by giving some small benefits to one group while turning that group against others.

We, in the United States, tsk-tsk over the failure of these fledgling democracies. It can’t happen here, we say. After all, the United States is the world’s oldest democracy, right?

Originally, our Constitution only guaranteed the right to vote to white men who owned property. Also, it included a number of anti-democratic provisions. The electoral college is only the best known of those. Originally, for example, state legislatures chose the U.S. senators, not voters.

What’s more, the Constitution did not extend its protections of individual rights to the state governments. The first five words of the first ten amendments to the Constitution, often referred to as the Bill of Rights, are “Congress shall make no law . . . ” In other words, the Bill of Rights was a protection of the rights of states to behave as they wish, and many of the states did not respect individuals’ rights. It was not a protection for the rights of individuals. Remember that in today’s federal system, most power resides in the state governments, not our national government; not even the provisions regarding slavery, and the devaluation of one in six Americans into three-fifths of a person. As a result, the America of 1789 was no democracy.

The reason for this arrangement is simple. The Constitution was drafted by America’s elites: white, wealthy, Protestant men of property, many of whom owned slaves. They did not want to give power to the people. After all, the people might want to take away some of the power and privilege these men had enjoyed in Georgian England. Black people, women, and poor whites might combine forces to spread their wealth more equitably. The American Revolution may have shorn the United States from its motherland, but the colonies’ elites did not want to give up their status. As a result, they designed a system designed above all else to protect their position.

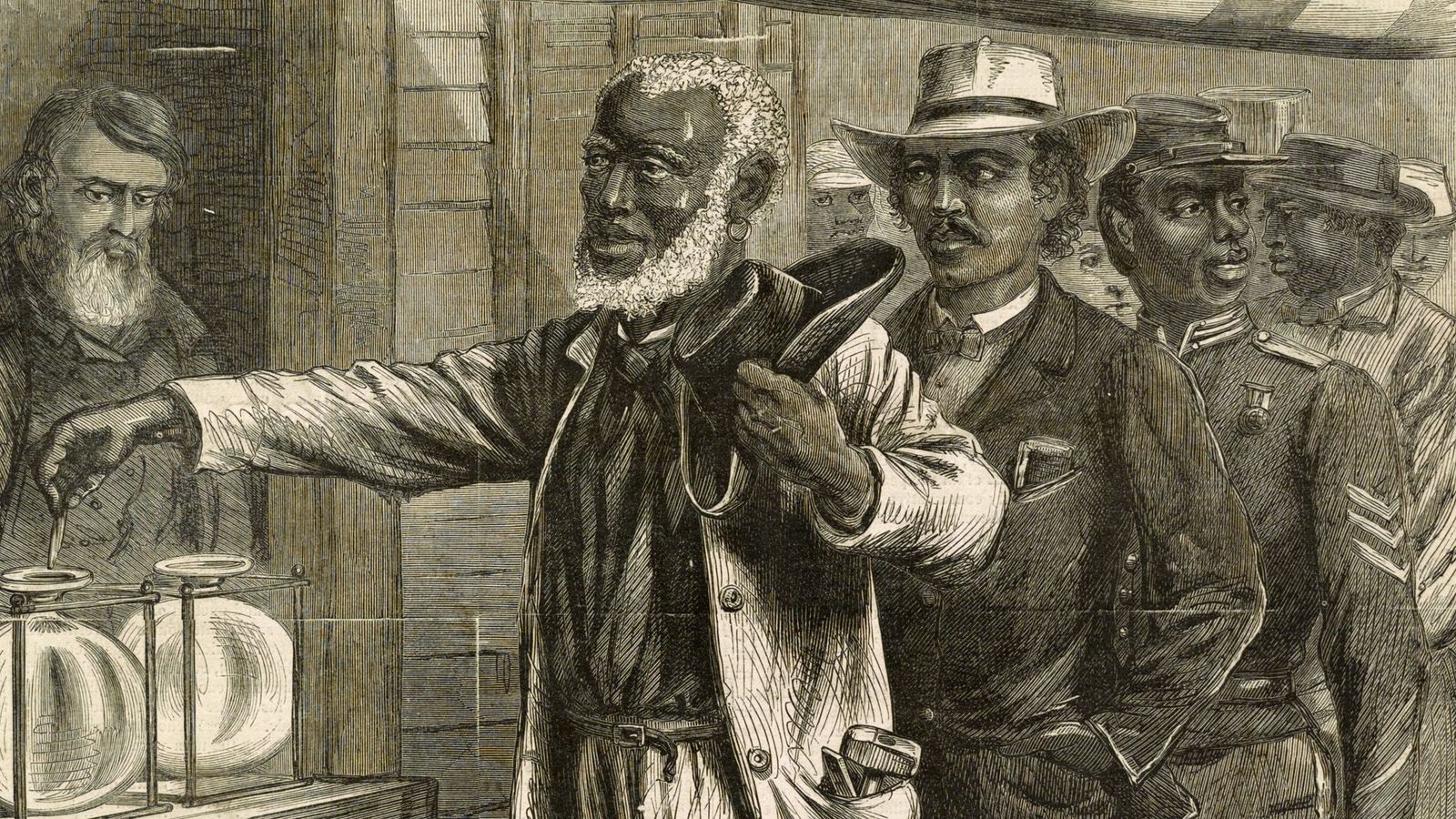

Over time, despite the protections the wealthy had baked into the system, advocates for marginalized groups would gradually achieve change. Populist reform, however, would never come easily. The bloodiest war in our nation’s history resulted in the passage of three amendments to our Constitution: the Thirteenth to ban slavery, the Fourteenth to extend the protections of our Constitution over the state governments, and the Fifteenth to guarantee Black men the right to vote. That was certainly a glorious, democratic moment, but the triumph was short-lived.

Over time, white elites would reassert their supremacy by whittling away at those rights in the courts and through state legislation, and by intimidating those individuals who dared to try to employ those rights and their supporters. That intimidation involved nothing short of terrorism, up to and including extra-judicial lynchings and the destruction of entire communities such as the Greenwood district of Tulsa, Oklahoma, and the Florida communities of Rosewood and Ocoee. In relatively short order, those three amendments weren’t even worth the paper they were written on.

At the same time as the anti-slavery movement was gaining steam, the original feminist movement was also starting up. The so-called “suffragettes,” mostly white women of privilege, wanted to vote as did their husbands and brothers. Many of them campaigned aggressively against passage of the Fifteenth Amendment guaranteeing Black men the right to vote out of fear that this action would make their success less likely. That position was both unfortunate and provident. On the one hand, it created a deep rift between feminists and People of Color that has yet to heal. On the other hand, they did not achieve their goal for another fifty years, until the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified in 1920.

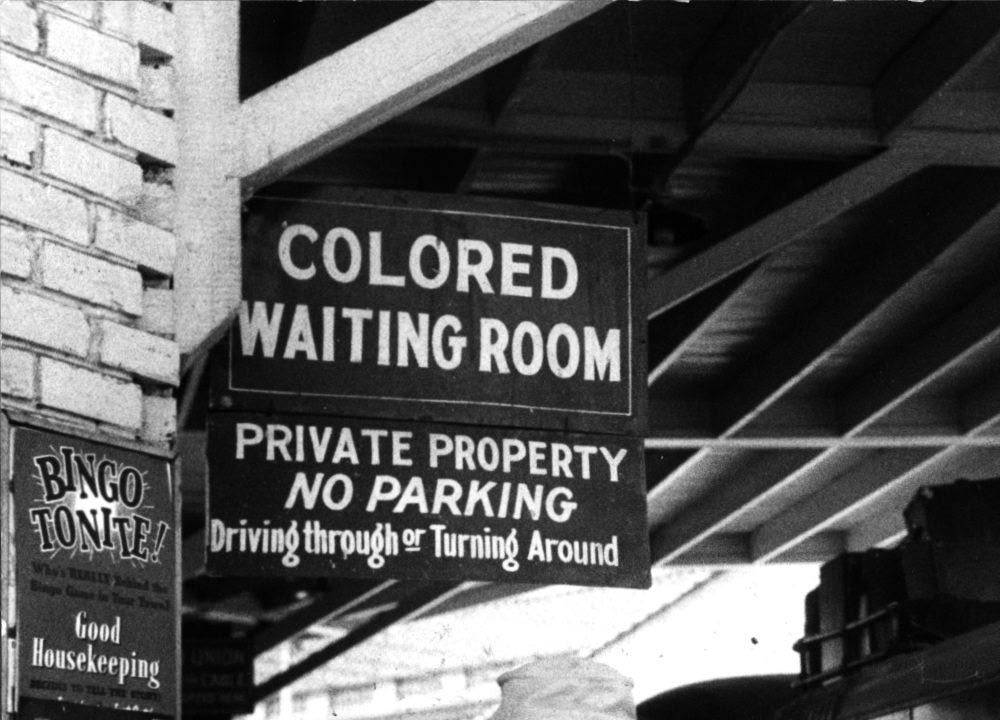

Meanwhile, much of America was ruled by white, racist authoritarian governments, colloquially referred to as “Jim Crow.” Ironically, designating those regimes with that moniker likely makes them seem less violent and extreme than they were in reality. In fact, Germany’s Nazis looked favorably on those governments, seeking to recreate those white totalitarian regimes in the Fatherland. The way white Americans had subjugated native Americans particularly impressed the Nazis. Nevertheless, the Nazis believed that some of the American Jim Crow rules went even beyond what they were willing to impose. So much for American democracy at the time; even Hitler thought we went too far.

The real beneficiaries of Jim Crow, however, were not the poor whites who engaged in these terrorist acts and for whom racism became a calling card. The real beneficiaries were the elites, who held onto their power even after they had been supposedly dispossessed after the Civil War. We may have outlawed slavery, but Jim Crow created a system of servitude that differed only in name and still provided the wealthy with subjugated, cheap labor they could exploit. Whenever people of any background sought to improve their circumstances at the expense of the superrich, those elites appealed to racism to stop any threat to their status. After all, it was a union meeting, not a civil rights meeting, that prompted one of the deadliest race massacres in our history, in Elaine, Arkansas, in 1919.

Whenever people of any background sought to improve their circumstances at the expense of the superrich, those elites appealed to racism to stop any threat to their status.

It was not until the 1960s that America finally set the ground rules that would make it a true, multi-racial democracy. In the wake of the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s, driven at least in part by Black American servicemen who fought Nazism overseas only to return to its inspiration here, Congress passed a trio of fundamental civil rights laws: the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Civil Rights Act of 1968, also known as the Fair Housing Act. For the first time in American history, discrimination based upon race would be truly illegal, and the right to vote would be guaranteed to all.

Turning this legislation into reality has not been easy, however. President Lyndon Johnson, who had led the fight for those three pieces of legislation, predicted that the Democratic party would lose the South for a generation as a result. And indeed, there would be a reaction. From 1968 until 1992, Democrats would only elect a president once, a moderate southerner, Jimmy Carter, and only for four years. The Republicans explicitly ran racist campaigns. Richard Nixon’s “southern strategy,” for example, included a promise that he wouldn’t enforce the recently-passed civil rights legislation.

Ronald Reagan won the presidency arguing for “states’ rights,” the Confederacy’s pro-slavery language, and against Black “welfare queens.” And George H.W. Bush demonized his Democratic opponent Mike Dukakis in attack ads warning white suburban voters that Dukakis would loose violent Black felons upon them. Southern Democrat Bill Clinton, who finally broke the Republican chokehold on the White House, would do so by soft-pedaling his anti-racism. Really, it would not be until America elected a Black man, Barack Obama, President of the United States in 2008, that it would seem the Civil Rights movement finally bore fruit.

Ironically, Obama was no firebrand liberal. Likely, the most radical thing about our forty-fourth President was his race. Nevertheless, his election was a shock to the system, and a wake-up call for white America. Although he obviously received a substantial portion of the white vote, Obama really owed his victories, especially his re-election victory in 2012, to Black voters. Indeed, 2012 is the only presidential election in our history in which Black voters cast ballots at a higher rate than their white compatriots. This high turnout was so unexpected that Republican Mitt Romney believed he had won on election day . . . until the final tallies started coming in.

The racism of many of Obama’s opponents is undeniable. Consider the following. Even if you don’t support his politics, his wife Michelle, is an inspiration. A successful attorney educated at Princeton and Harvard, a doting mother and devoted spouse, an individual imbued with dignity and decency, someone who has never been touched with a hint of scandal, she is impossible not to like and respect. Nevertheless, many of Obama’s opponents instead revere Melania Trump as a First Lady, a former stripper with little education, and a third wife with no accomplishments outside of her looks who has never shown any public impulse. The only material advantage she has on Michelle is the color of her skin. But sadly, for many Americans, that is enough.

Despite the moderation and respect with which Obama governed, his election signaled a perceived crisis to many white Americans. No longer were white Americans guaranteed to be in the majority. America’s demography was changing, and California, with its majority-minority population and progressive politics, appears to be America’s future.

The powers-that-be were especially fearful. They easily supported democracy and freedom when that position did not result in substantive social and political change. In other words, as long as such change did not threaten their privileged position. But as the formerly disempowered gain political influence, they will start to demand their place at the table, and this threatens the status quo. The emerging racially diverse majority might no longer favor the order that empowered the wealthy, white minority, instead demanding greater economic equity and corporate accountability. What could the elites do to protect their status?

We like to think of America as a classless society. That narrative, however, is just a myth. Not too long ago, I was shocked to read an academic paper which tried to determine why some directors who had served on the boards of failing companies get new jobs as corporate directors while others don’t. Their finding? It wasn’t whether he (because they’re almost always a he) went to an elite school, or served the community in a service organization, or found success in other ventures. No, the only factor that influenced whether these disgraced board members got new jobs was whether the director was born in an upper-class family, as indicated by their inclusion in the Social Register. In other words, to gain unqualified access to America’s power structure, the only thing you need is a privileged background. So much for the meritocracy.

. . . the elites need to divide the rest of society against itself, for fear that the masses of non-elites will combine their efforts to change the system.

The number one priority of this elite is the protection of their status, but how can they succeed in this task given their small numbers in a representative democracy? The answer is clear: they need to recreate the dynamic that allowed a small group of large slaveowners to take their entire nation to war.

The strategy is sometimes referred to as “divide-and-conquer,” but that is an oversimplification. Yes, the elites need to divide the rest of society against itself, for fear that the masses of non-elites will combine their efforts to change the system. Given humans’ propensity for identification of in-group members and out-group members, that task is relatively easy. After all, just look at a middle school playground to see how the students divide statuses among themselves. The challenge, however, is ensuring certain groups feel that they have enough stake in the system that they will defend it. This is where the elites dole out certain levels of privilege to keep something approaching a majority on their side.

Consider the case of the suffragettes. If the privileged women had realized they had common cause with People of Color in democratizing American society, everyone would have achieved the franchise, and power would have shifted from the elites. However, the elites essentially sent a message to women that they will give white women the vote, but not Women of Color. The white women made that deal and jettisoned their initial support for universal suffrage.

Similarly, there is no greater threat to the elites’ status than organized labor. The increase in inequality in America can be tracked almost exactly with the decline in union membership over the past fifty years. One would think all employees would be enthusiastic supporters of the labor movement considering how it delivers higher wages and benefits to all. But by dividing employees by race, gender, and the type of work they perform, the elites have been able to drive wedges between workers, resulting in the marginalization of what should be one of the most powerful forces for equality and justice in America.

There is no question that the leaders of these forces for equality have caused many of their own problems. The corruption of some labor leaders and the racism of some feminists is a stain on their movements. But the elites have taken advantage of these limited scandals to turn Americans against these movements that would otherwise have brought them benefits.

Only one solution exists for America to truly achieve equality and justice: to work together. Each time we look unfavorably at another marginalized group, we need to redirect our resentment at the true oppressors in our society: the elites who control our economy. Until we can do that, the elites will continue to succeed in their efforts to control society and enrich themselves at the expense of the rest of us.

Member discussion