This story began in the autumn of last year when I read these words on a poster: “2020 celebrates Ireland’s connection with Frederick Douglass on the 175th anniversary of the months he spent visiting the country.”

And I realised I had never heard of Frederick Douglass.

The organisation I volunteer for had decided to cooperate with Cork University to celebrate the 175th anniversary of Frederick Douglass’s visit to Cork in 1845. Together they organised a week-long celebration with a series of talks, lectures, and creative webinars on music and art to commemorate his visit, culminating with a powerful closing event on the 14th of February, his birthday.

I recall feeling ashamed at having to admit I had never heard of him.

All the more because on the backdrop of the killing of African American George Floyd in 2020, police brutality, and the rise of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement worldwide, I began researching the reasons for systemic racism in the USA. As I did not go further back than the Jim Crow Laws introduced after Douglass’s death, I did not include the cross-Atlantic trade of enslaved people and the ensuing global abolitionist movement, and thus failed to discover its famous representative, Frederick Douglass.

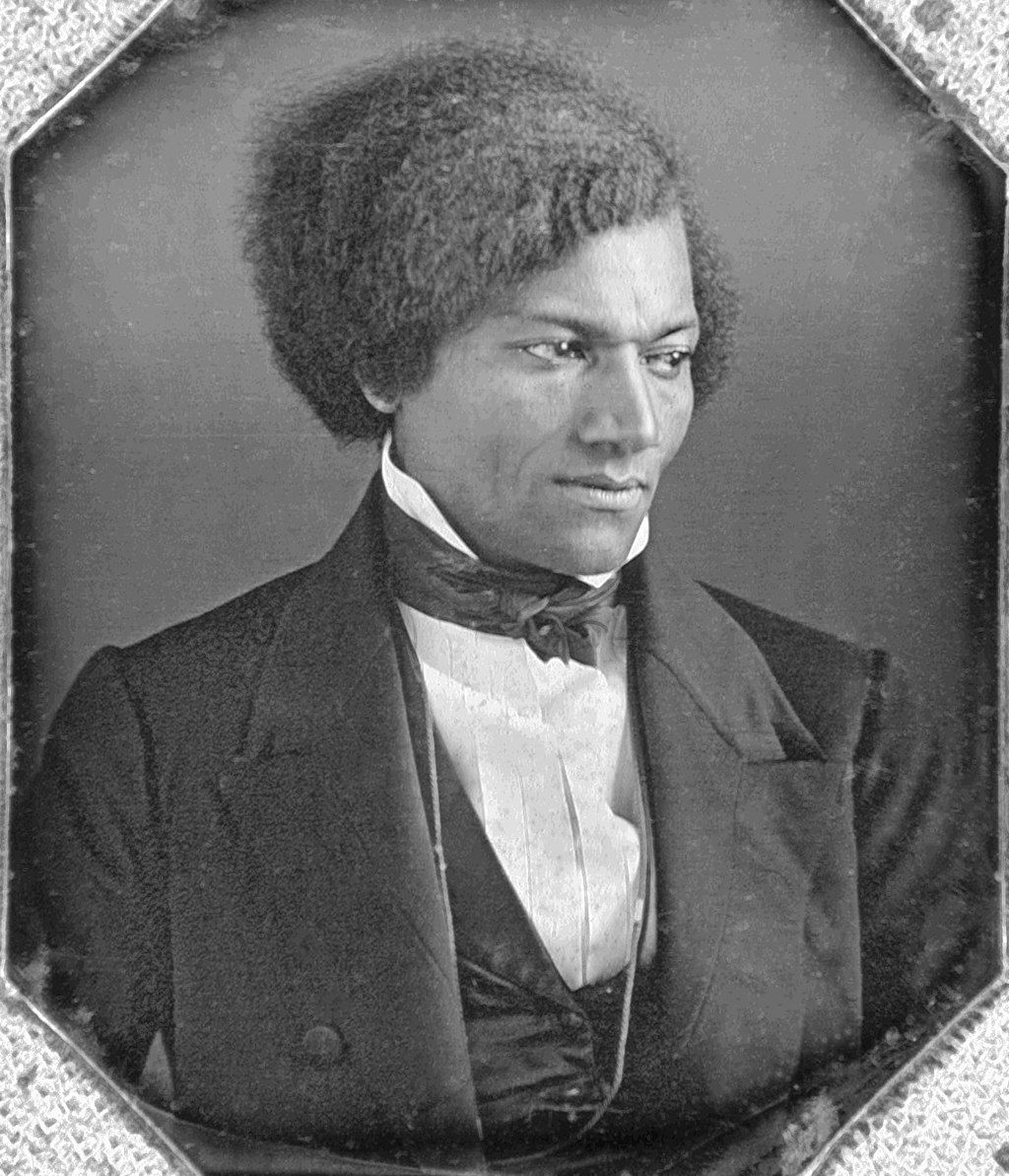

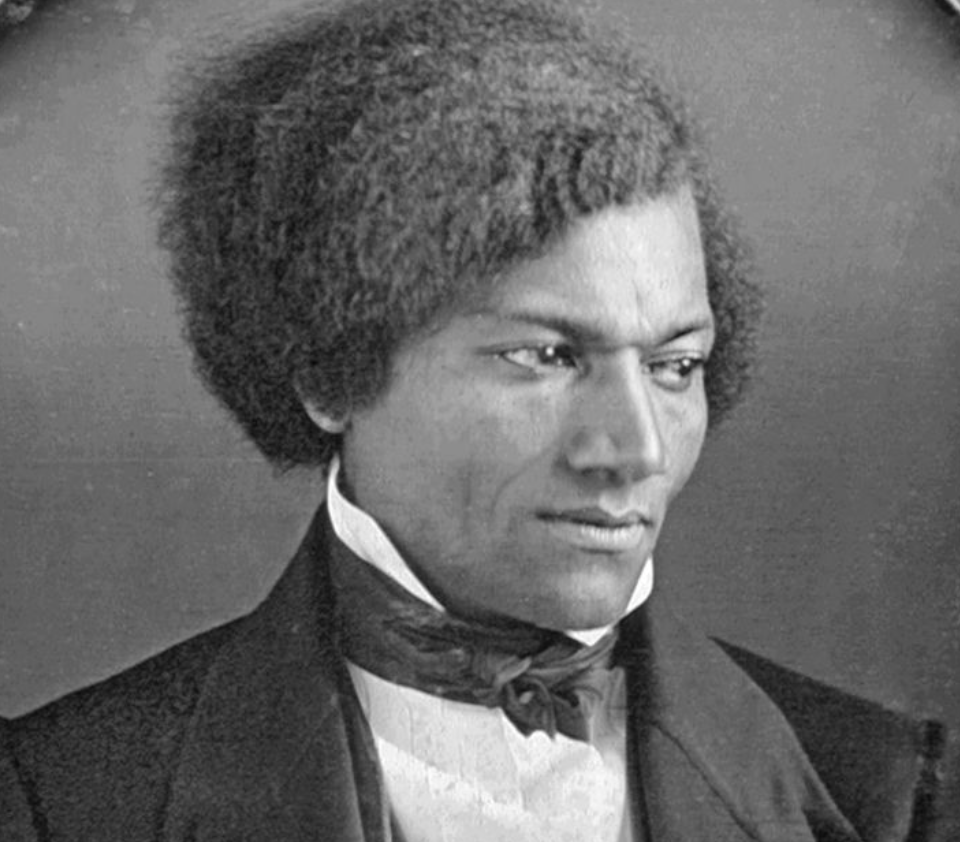

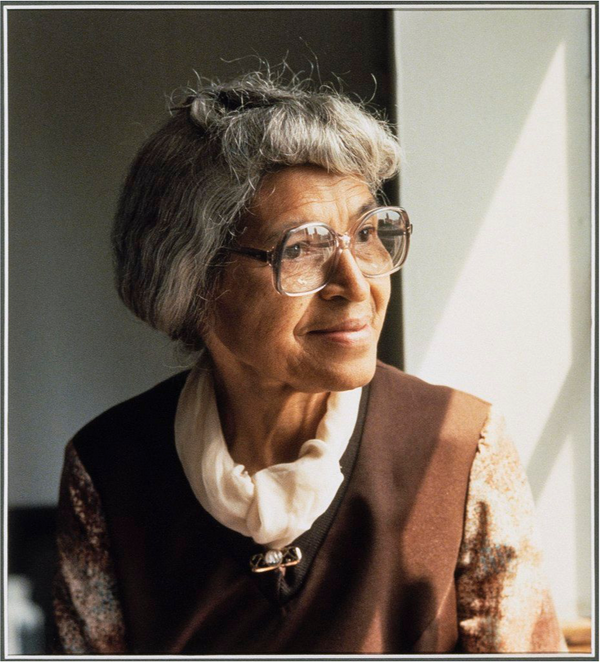

Retouched portrait of orator, writer, and statesman Frederick Douglass in the 1840s. After escaping a life of bondage, Douglass became a leading advocate for the emancipation and civil rights for African Americans as well as all oppressed people. Image source Wikimedia Commons.

I have chosen to write about him and his visit to Ireland because I now wish to look into the life of this inspiring man and share my findings especially with those on this side of the Atlantic, who, like me, may never have heard of this historical figure and how, through the power of his personality and words, he influenced the many people with whom he came in contact.

Perhaps, too, many Americans today are unaware of his trip to Ireland in 1845. I have chosen Frederick Douglass in Ireland by Laurence Fenton (2014) as my main source, a well-researched and compellingly written account of Douglass’s tour of Ireland. I will also delve into my copy of Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845) to garner his original words.

The most celebrated Black man of his era, Frederick Douglass was also the most photographed American of any race in the 19th century. He was the first Black person appointed to an office requiring senatorial confirmation--in 1877, President Rutherford B. Hayes nominated him to be the U.S. Marshal of the District of Columbia. In 1889 President Benjamin Harrison appointed him Minister to Haiti, a post he would hold until 1891.

If he were among us today, Douglass would certainly be a media-exposed celebrity inspiring generations of followers both young and old. It is in this light I would like to write about Frederick Douglass, the celebrity whose life was the subject of great public interest.

Reading about his life experience, I have been particularly struck by the depth of Douglass’s pain at the plight of his people as illustrated by the effect the songs of the enslaved had on him, along with his anger at the misinterpretation of the reasoning behind such songs. As he wrote:

I have often been utterly astonished, since I came to the north, to find persons who could speak of the singing, among slaves, as evidence of their contentment and happiness. It is impossible to conceive of a greater mistake. Slaves sing most when they are most unhappy. The songs of the slave represent the sorrows of his heart; and he is relieved by them, only as an aching heart is relieved by its tears. At least, such is my experience. I have often sung to drown my sorrow, but seldom to express my happiness. Crying for joy, and singing for joy, were alike uncommon to me while in the jaws of slavery. The singing of a man cast away upon a desolate island might be as appropriately considered as evidence of contentment and happiness, as the singing of a slave; the songs of the one and of the other are prompted by the same emotion. (The Narrative, pp. 27-28)

A Man of Experience

A father of five whose youngest child died at eleven and grandfather to eighteen grandchildren, eleven of whom died before adulthood, Frederick Douglass married twice. His first wife, Anna Murray-Douglass, was Black, and his second wife, Helen Pitts Douglass, white.

Douglass’s claim to fame was, among others, his prolific power over words and how he used them. Words which could get to the core of belief systems and unhinge them by communicating to his listeners his particular perspective—that of the enslaved.

He became a passionate abolitionist in his early twenties and up to his trip to Ireland in 1845, travelled the U.S. giving anti-slavery lectures.

An imposing figure and impressive speaker, he quickly became the biggest draw on the anti-slavery circuit in America.

Douglass used his personal stories and experiences as his rhetorical tool. As an engaging storyteller, he could develop empathy, deliver impact, and activate change.

Initially, he described only the pain of the enslaved but later he went on to attack the systemic structures sustaining slavery, which included not only the rich plantation owners in the South but also the church. For Douglass: “. . . of all slaveholders with whom I have ever met, religious slaveholders are the worst.” (The Narrative, p. 77)

He uses as example Methodist ministers who referred to the hard-working hands and “muscular frames” of the enslaved and compared them with the long delicate fingers and slender frames of their “white masters,” pointing out that this was proof that God had designed them for physical work and their masters for thinking. (Frederick Douglass in Ireland, p.42)

As evidence of the horrendous treatment of millions of enslaved African Americans, Douglass would tell his personal story to counter the disbelievers who regarded his reports as baseless fake news.

Sometimes, he was introduced to the public as a graduate from the institution of enslavement with his diploma written on his back, confirmed by the deep scars from the whippings he had received while in bondage. (Frederick Douglass in Ireland, p.37)

Abolitionists, thus, liked to present him as proof that there was no foundation in enslavers’ arguments that the enslaved lacked the intellectual capacity to act as independent American citizens. Conversely, Northerners often found it hard to believe that such a great orator could have once been enslaved. (Frederick Douglass in Ireland, p.44) He certainly did not fit into the imagined category of an enslaved person.

Pain, Loss, and the Power of Words

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, later Douglass, was born into slavery and never knew his exact age, posthumously determined to be 1818. This privilege was known only by his enslaver, Capt. Aaron Anthony, who was himself the overseer of a wealthy landowner and enslaver in eastern Maryland. Frederick chose February 14 as his birthday, remembering that his mother whom he had rarely seen, called him her “Little Valentine.”

He was prevented from forming a relationship with his enslaved mother, Harriet Bailey, who after his birth was sent back to work on a neighbouring plantation about twelve miles away. She only managed to visit Frederick after her day’s work a few times before her death in 1826. The pain of never knowing her remained a lifelong source of grief for him:

. . . My mother and I were separated when I was but an infant . . . . It is a common custom, in the part of Maryland from which I ran away, to part children from their mothers at a very early age . . . . I do not recollect of ever seeing my mother by the light of day. She was with me in the night. She would lie down with me, and get me to sleep, but long before I waked she was gone. (The Narrative p.18)

Light in skin colour, he was presumed to be of mixed race. Though he tried throughout his life to find out, he never discovered who his father was: “The opinion was . . . whispered that my master was my father [Aaron Anthony]; but of the correctness of this opinion I know nothing.” (The Narrative, p. 17)

Frederick’s emotional bond was to his maternal grandmother, Betsey Bailey, who brought him up until at the age of seven or eight he was separated from her and sent to work as a servant at the Wye House plantation, where his presumed father, Aaron Anthony, was employed as estate manager. (Frederick Douglass in Ireland, p.5)

For Frederick the child, this was again another traumatic loss. Perhaps these losses were the reasons why throughout his life he would seek and feel happiest in the company of women.

His first pivotal encounter with the inhuman treatment of enslaved people was witnessing his enslaver, Aaron Anthony, whip his mother’s younger sister, his Aunt Hester. As his “possession,” she had disobeyed his order to not go out with an enslaved man. The abuse and cruelty he witnessed were horrific for the eight-year-old Frederick who, unknown to Anthony, was hiding in the nearby pantry. Before he began whipping his aunt, Anthony stripped her to the waist, tied her hands together with a rope and made her stand on a stool placed under a hook, and then tied her bound hands to the hook, leaving her to stand on her tiptoes and await her fate. Frederick watched with horror as his “master” with his whip cut into his aunt’s back with such brutal force that “soon the warm, red blood (amid heart-rending shrieks from her, and horrid oaths from him) came dripping to the floor.” (The Narrative, p. 21)

This, I can imagine, was a defining moment for young Frederick who remained in the pantry long after the “bloody transaction was over” for fear that it would be his turn next.

He was to witness such cruelty many times in his early life with Aaron Anthony.

Unknown to him then, the weapons he would later use to fight the discrimination and oppression of his people would not be through violence which he would often enough experience, but through his words with which he would become a master in precision.

In 1826, Aaron Anthony died, and Frederick was sent to Baltimore in Maryland and given to serve Hugh Auld, a relative of Anthony, where he lived for about seven more years.

Hugh Auld’s wife, Sophia, who wanted a companion for her son, ensured that Frederick was properly fed and clothed, and given a proper bed to sleep in. He described her as a kind and tender-hearted woman who treated him “as she supposed one human being ought to treat another.” (The Narrative, p. 45). She also began teaching him the alphabet.

Hugh Auld disapproved of his wife’s teaching, feeling that literacy would encourage the enslaved to strive for their freedom, and so Sophia stopped the lessons. In fact, under her husband’s influence. she made a U-turn and became very intolerant, convinced, too, that “education and slavery were incompatible with each other.” (The Narrative, p. 46)

In Maryland, as in many other states of legal enslavement, it was forbidden to teach enslaved people how to read and write.

These early lessons fired Frederick’s passion for the written word, and so he continued his learning in secret by exchanging bread for lessons from the poor white boys with whom he played in the neighbourhood and by tracing the letters in old schoolbooks used by Sophia Auld’s son. Later, at his other workplaces, he secretly organized Sunday school and taught other enslaved people to read. This, he wrote, was a time of mutual love between himself and his people. (The Narrative, p. 80)

Around the age of twelve, Frederick discovered and bought his first book, The Columbian Orator, an anthology first published in 1797, which every white schoolboy carried in their satchel. It contained heroic essays, patriotic speeches, and dialogues to support their learning, reading, and grammar. These texts introduced him to the power of words and further broadened his way of thinking, leading him to question and condemn the institution of enslavement.

Further, they defined his views on freedom and human rights and sowed the seeds of his powerful oratorial skills (Frederick Douglass in Ireland, p 15).

He read these writings over and over again, and in his own words, they “gave tongue to interesting thoughts of my own soul, which had frequently flashed through my mind, and died away for want of utterance.” (The Narrative, p. 47).

They also triggered his journey to discover his voice and at the same time fed the loathing he developed for the system of enslavement and its perpetrators, the enslavers. It was a mentally difficult time for the young Frederick: the greater the awareness of his and his fellow enslaved people’s predicament, the greater his torment and the stronger his desire for freedom.

It was in The Orator, too, that Frederick was introduced not only to the Irish satirist, politician, and playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s mighty speeches on Catholic emancipation, but also to the great Irish liberator Daniel O’Connell’s speeches on liberty and social justice.

The Decision

One day, while down on the wharf, he went, unasked, to help two Irish men unload “a scow of stone.” The job finished, they asked him if he was an enslaved person for life. On his affirmation they felt so sorry for “so fine a little fellow” that they advised him to run away to the north and freedom. Not trusting them as he had heard stories of enslaved people being encouraged to flee only to be caught by their so-called “friends” and sent back to their owners for the reward, he pretended not to understand their advice. But fascinated at the thought, Frederick resolved from that moment to run away. (The Narrative, p.49)

In the following years, Frederick experienced a variety of labour and enslavers, and learned the trade of “calking”; that is, how to make a boat watertight with sealing material. (The Narrative, p. 92)

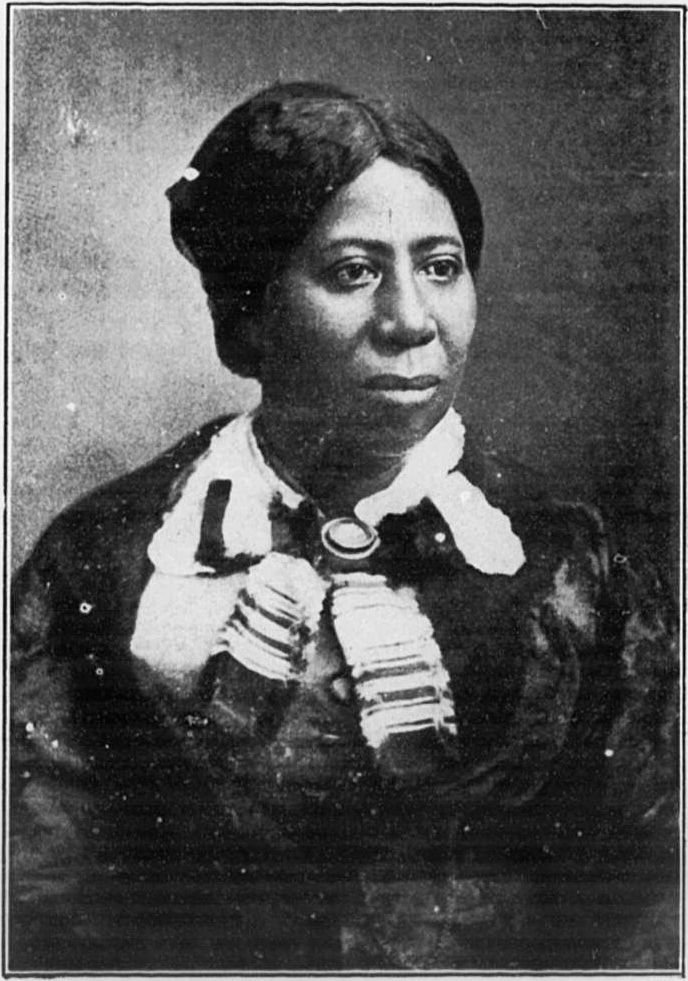

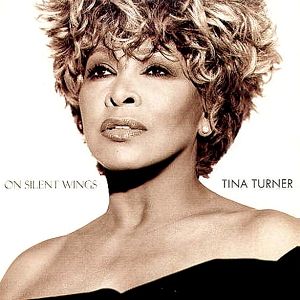

Photograph of Anna Murray Douglass (1813–1882), the first wife of Frederick Douglass, first published in Rosetta Douglass Sprague, “My Mother As I Recall Her,” 1900. Image source.

In 1837, at a debating club, he met his future wife Anna Murray, a free African-American housekeeper, who with her savings helped Frederick escape his bondage in 1838. At the age of twenty, Frederick, after several failed attempts, finally arrived in New York where he soon married Anna Murray.

In 1838, the couple moved to Massachusetts where Frederick changed his surname to Douglass and where both he and Anna worked for the Anti-Slavery Society.

Even as her husband emerged as one of the most distinguished writers of the 19th century, Anna Murray-Douglass remained largely illiterate. She was a great support to Douglass throughout her life and a person whom he highly respected and relied upon.

During his lifetime, Frederick Douglass lectured not only on anti-slavery but branched out into temperance, women’s rights, racism, and social justice for all; he edited newspapers, advised presidents; and wrote three versions of his life story. It was the publication in 1845 of the first and most popular of his autobiographies — Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave—that became a bestseller, especially in Europe, elevating him to international prominence and triggering his visit to Ireland.

More from the Frederick Douglass: An American in Ireland series by Sylvia Wohlfarth

About Sylvia Wohlfarth

n

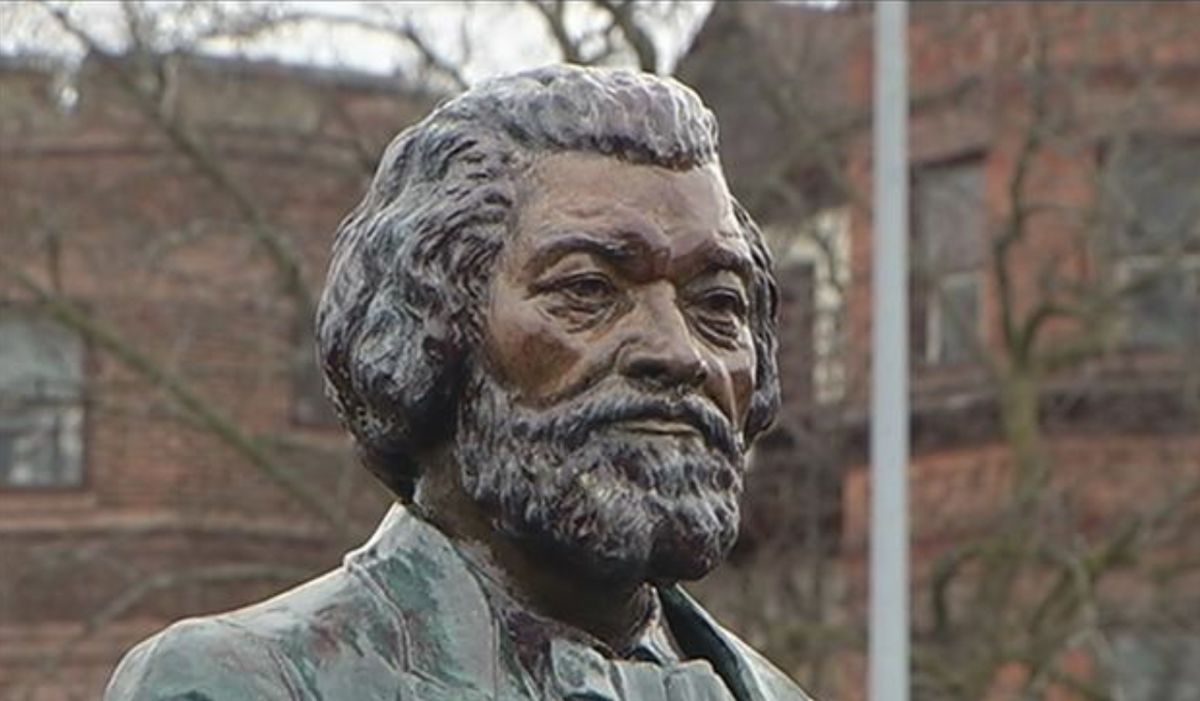

Top photo: Statue of Frederick Douglass atop the stairs of the 77th Street entrance at the New York Historical Society. Image source Wikimedia Commons.

Member discussion