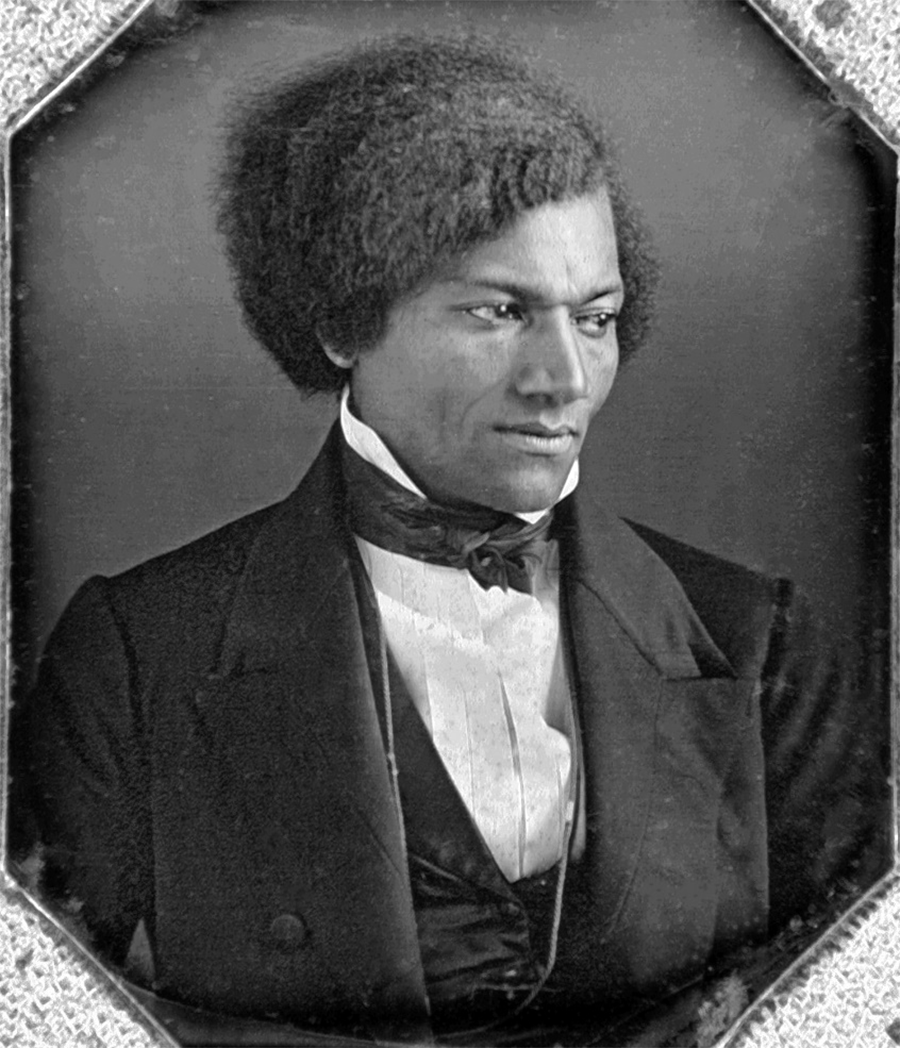

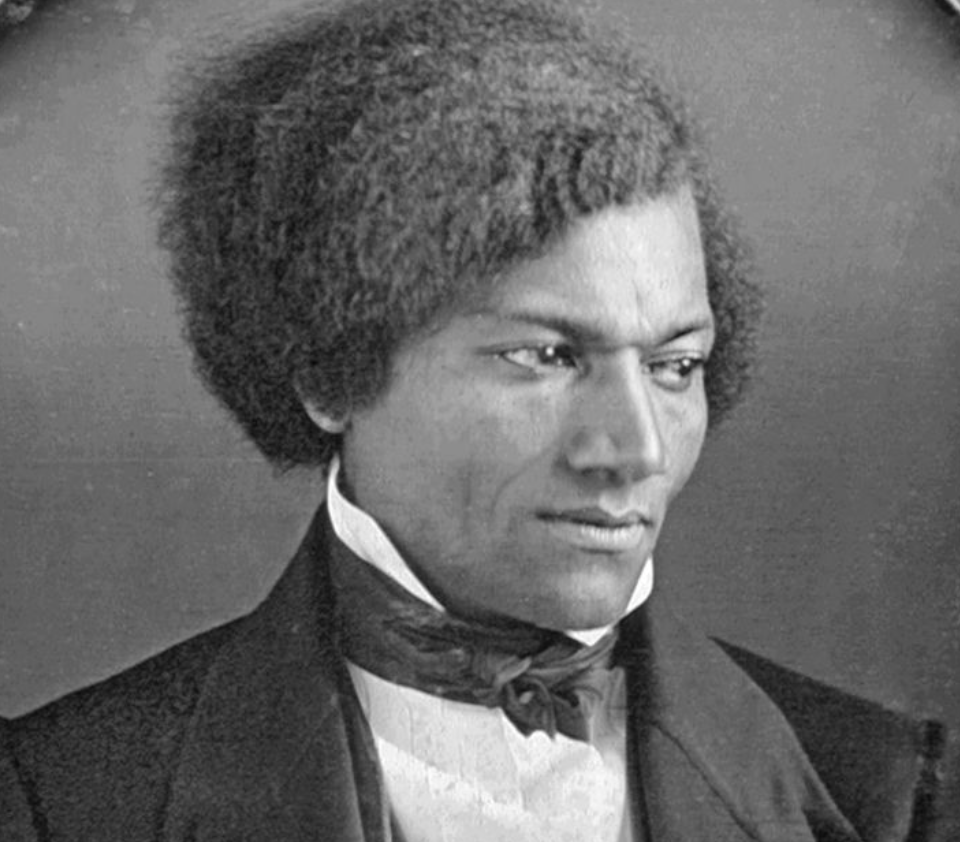

During his lifetime, Frederick Douglass lectured not only on anti-slavery but also on temperance, women’s rights, racism, and social justice for all; he edited and owned newspapers; advised presidents; and wrote three versions of his life story. It was the publication in 1845 of his first and most popular autobiography — Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave — that became a bestseller, especially in Europe. This levered him to international prominence and triggered his visit to Ireland in that same year.

Douglass wrote the Narrative to counter accusations that he was an impostor. How indeed could a young man, a formerly enslaved man, have learned the linguistic and rhetorical skills he used in his speeches on behalf of the American Anti-Slavery Society? To prove his authenticity, Douglass had to give details of names, dates, and places, information which put him at risk of being recaptured into enslavement. Though he had escaped to a so-called Free State, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 meant that Douglass was in constant danger of being captured, returned to his ‘master’ and punished. (Lee Jenkins. Beyond the Pale, p. 80–81)

Persuaded to travel to Britain and Ireland for his safety, and where, too, he could promote the work of the American Anti-Slavery Society, Douglass reluctantly agreed to leave his wife and four small children and went into self-exile between 1845 and 1847.

The idea, however, of visiting Ireland was not strange to him. He had long been an admirer of the Irish nationalist and vociferous abolitionist Danial O’Connell, famous for his flaming speeches on freedom, social justice and, unusual for politicians at the time, his strong stance against enslavement. Douglass’s wish was to meet him.

Free from Colour

There were once times and places in the ‘Western World’ where the colour of one’s skin did not matter. One such place and time was Ireland in 1845, when Douglass set sail on August 16th from Boston to Dublin via Liverpool on a two-week Atlantic crossing.

He was accompanied by a thirty-eight-year-old white abolitionist, James Buffum, and a famous musical family, the Hutchinsons. With their anti-slavery songs, the Hutchinsons had, on many an occasion, been the supporting act to Douglass’s lectures. (Laurence Fenton. Frederick Douglass in Ireland, p. 47)

Like his companions, Douglass had bought a first-class ticket but, because of his colour, the ship’s captain forced him into steerage, the lowest passenger class. Buffum joined him in solidarity. The Hutchinsons, however, persuaded the captain to allow Douglass come up to the promenade deck each morning. Thus, he could enjoy some fresh air and communicate his anti-slavery message to many of the passengers. He also sold copies of the Narrative much to the disgust of several American passengers. (Frederick Douglass in Ireland, p. 49)

On the eve of their arrival, Douglass was invited to give a lecture on abolitionism. He had barely begun when a group of American passengers verbally attacked him with racial insults. The hecklers were so disruptive and abusive that despite the intervention of an Irish soldier and supporter, Captain Thomas Gough, the event almost ended up in a free-for-all fistfight.

Wanting to avoid further conflict and under threat by some male passengers to throw him overboard, Douglass headed back into steerage. The ship’s captain put a stop to their hounding by threatening the brawlers with imprisonment below deck. English newspapers got wind of the incident and reported it, giving Douglass his first public press exposure. (Frederick Douglass. My Bondage and My Freedom, p. 367)

The confrontation on board the ship only strengthened Douglass’s determination to shed his enslaved identity once and for all. To achieve this, he vowed to further his knowledge, self-improve in the land of his paternal ancestors, spread abolitionism, and — like celebrities today — promote his lectures, as well as print and sell the Narrative. (Beyond the Pale, p. 81). His birth name of Bailey being an Irish name, Douglass, I believe, liked to think he was of Irish descent. And perhaps he was.

Douglass and his companions arrived in Ireland on August 30. He was immediately struck by the warm welcome he received and amazed at: “ . . . the total absence of all manifestations of prejudice against me, on account of my color. I find myself not treated as a color, but as a man.” (Frederick Douglass: Letters to Antislavery Workers and Agencies, p. 660)

He contrasted this with his treatment in America: “The land of my birth welcomes me to her shores only as a slave, and spurns with contempt the idea of treating me differently.” (Letters to Antislavery Workers and Agencies, p. 655)

It should be mentioned that Douglass was not the first Black abolitionist and former enslaved person who was welcomed in Ireland. Others included Olaudah Equiano, author of The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, who visited in 1791.

For most of his stay, Douglass was hosted by members of the Quaker community. This included his Dublin publisher, Richard D. Webb, who had agreed to print an Irish edition of the Narrative.

An impressive speaker, Douglass became a popular figure in Ireland, quickly earning the reputation of a man “possessing the power of debate with wit, arguments, sarcasm and pathos.” (Frederick Douglass in Ireland, p. 38)

His visit there left a lasting impact on him. It was a turning point in his life as this, he noted, was the first time he had ever been treated as an equal within a society. He wrote about this first-time experience of freedom from racial discrimination as follows:

Eleven days and a half gone and I have crossed three thousand miles of the perilous deep. Instead of a democratic government, I am under a monarchical government. Instead of the bright, blue sky of America, I am covered with the soft, grey fog of the Emerald Isle [Ireland]. I breathe, and lo! the chattel [slave] becomes a man. I gaze around in vain for one who will question my equal humanity, claim me as his slave, or offer me an insult. I employ a cab — I am seated beside white people — I reach the hotel — I enter the same door — I am shown into the same parlour — I dine at the same table — and no one is offended … I find myself regarded and treated at every turn with the kindness and deference paid to white people. When I go to church, I am met by no upturned nose and scornful lip to tell me, ‘We don’t allow niggers in here!’ —Frederick Douglass: My Bondage and My Freedom, p. 371)

Though skin colour was not an issue during his visit, there were some racialized comments in the press on Douglass’s “singularly pleasing and agreeable” appearance. The explanation given for his lack of typical negro features was that his parents were of mixed race. (Beyond the Pale, p. 91)

It was not unusual during this time to see Black men and women on the streets of Dublin. They were mostly servants, soldiers, or sailors and some Black singers and actors who performed regularly in the city’s theatres and concert halls. Though they made up only about a few hundred, this was enough for Dublin to have a Black population larger than any other European city except London. Other Irish port cities like Cork and Belfast also had a small Black population. Though there was no widespread racism, Black Women and children, in particular, would sometimes be stared at for their looks. Mixed marriages were not frowned upon. (Frederick Douglass in Ireland, p. 67)

At the same time, Minstrel shows with their Blackface acts were quite a regular feature in both England and Ireland. These were performed either by travelling American troupes or British or Irish impersonators.

Ireland, too, was historically involved in the slavery trade, albeit less than most. Many Irish merchants, especially from Cork, had amassed their wealth by supplying provisions to the Caribbean islands. The last recorded Irish slave ship, the Prosperity, sailed from Limerick to Barbados on July 31, 1718 carrying ninety-six enslaved people. (Frederick Douglass in Ireland, p. 68)

Ireland’s Struggles and the Human Family

Instead of the intended four days, Douglass stayed four months in Ireland, holding around fifty speeches to huge crowds and selling many of his books.

His lectures were a complete sell-out. People from all walks of life flocked to hear him speak. These included nationalists, women suffragettes, and the poor hoping to get information on North America as a possible country of emigration.

By mid-September, Douglass had delivered many lectures to huge crowds at venues ranging from Dublin’s City Hall to a local prison. He would skillfully grasp the attention of his audience, fascinating them with cracking a whip and presenting manacles and other instruments of torture used for punishing enslaved people which he had brought with him (Frederick Douglass in Ireland, p. 82)—a form of nineteenth-century sensation-seeking not unlike today’s social media exhibitionism.

In early October, Douglass and his companions set off to lecture in Cork, Limerick, and Belfast, with stop-overs in Wexford and Waterford.

With few railroads in the country, Douglass travelled by horse and carriage through often windy, rainy, coastal mountains and hilly countryside. An independent man, he contributed to financing the tour, organized his itinerary, and personally transported and sold his book. The accompanying singers and Douglass, a music lover, also sang at some of the events listening in return to Irish laments, which reminded him of plantation life.

During his trip, Douglass had plenty of opportunities to observe the plight of the Irish.

His visit coincided with Ireland’s many struggles for independence. He arrived aware of the country’s over 300-year history of British colonization and religious, economic, and political oppression.

Catholics in Ireland had been socially and politically marginalized by the British Penal Laws, which were introduced in 1695 and finally and fully repealed in 1829. Their impact was still strongly felt in Irish society in 1845. The laws had been designed to suppress Catholicism by forbidding its teaching and practice and to strengthen the Protestant stronghold on Ireland’s economy. The strategy was successful. By the mid-1800s, Irish Catholics who constituted eighty percent of the population owned less than one-third of the land.

The majority of Irish poor lived as tenant farmers on the large estates of mostly absentee English landlords. They sold their crops to pay their rent. Families lived on potatoes, which they grew on their little plots, sometimes adding buttermilk and, occasionally, herring fish to their poor diet. The overworked soil produced poor quality potatoes, insufficient to sustain families and which, along with overcrowded living conditions, led to disease and ill-health. No other country was as reliant on the potato as Ireland.

On Douglass’s arrival in August 1845, Ireland was on the verge of the Great Irish Famine (also known as the Great Irish Potato Famine), which lasted four years and would lead to mass emigration and death. It was the last incidence of mass hunger in the western world.

While grain and meat continued to be exported from Ireland to Britain, around one million people died of starvation or from other famine-related diseases.

Between 1846 to 1854, wanting to rid their estates of impoverished farmers and labourers, landlords evicted an estimated 500,000 people.

Over a million Irish people emigrated during the famine, of whom forty-nine per cent went to the United States. The population of Ireland, once almost eight million in the 1830s, was reduced to around four million by 1900.

The first stages of the potato crop failure due to the potato blight occurred in early September of 1845 while Douglass was in Ireland. Its effects were in its very early stages and though Douglass did not mention the famine, he was astounded by the extreme levels of poverty he saw, much of it reminding him of his experiences in enslavement. In a letter to William Lloyd Garrison, a prominent American abolitionist and social reformer best known for his widely-read anti-slavery newspaper The Liberator, Douglass wrote:

I see much here to remind me of my former condition, and I confess I should be ashamed to lift up my voice against American slavery, but that I know the cause of humanity is one the world over. He who really and truly feels for the American slave, cannot steel his heart to the woes of others; and he who thinks himself an abolitionist, yet cannot enter into the wrongs of others, has yet to find a true foundation for his anti-slavery faith. —The Liberator, 27 March 1846; reprinted in Philip Foner, ed., Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass, vol. 1 (New York: International Publishers, 1950), p. 138.)

His thirst for knowledge had broadened Douglass’ view to include the sufferings of other peoples. Witnessing the depth of poverty in Ireland fundamentally altered his worldview:

“I believe that the sooner the wrongs of the whole human family are made known, the sooner those wrongs will be reached.” The Liberator, 27 March 1846; reprinted in Philip Foner, ed., Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass, vol. 1 (New York: International Publishers, 1950), p. 138.

Douglass, who had strong religious beliefs and led a strict temperance lifestyle, occasionally blamed the Irish for their misery on their alleged drunkenness and backwardness. The strategy behind this, too, was to win over temperance and abolitionist leaders and the British, especially Protestants. Thus, Douglass during his tour lectured not only on slavery but also on temperance.

His rejection of alcohol stemmed from his time as an enslaved man. He had often observed how enslavers, while allowing the enslaved people a few days off between Christmas and New Year, ensured they were completely drunk the whole time.

So, when the holidays ended, we staggered up from the filth of our wallowing, took a long breath, and marched to the field,-- feeling, upon the whole, rather glad to go, from what our master had deceived us into a belief was freedom, back to the arms of slavery. (Narrative pp. 74-75)

During his visit, Douglass happily befriended Ireland’s chief temperance crusader, Father Theobald Mathew (1790–1856). An enthusiastic teetotaller, Douglass took the pledge from Father Mathew at his temperance institute in Cork. However, the two men later parted company when Father Mathew on a speaking tour of the United States in 1849 refused to openly condemn enslavement because of his dependency on American financial support.

In general, Douglass’s anti-slavery message resonated strongly with the Irish public angry at the social and economic conditions suffered by the majority under the British. Especially under the influence of the famous liberator Daniel O’Connell, these anti-slavery sentiments were extremely fertile.

And as it happened, Douglass would meet and befriend Daniel O’Connell, his lifelong hero and source of inspiration.

More from the Frederick Douglass: An American in Ireland series by Sylvia Wohlfarth

-

About Sylvia Wohlfarth

Sources

Jenkins, Lee. Beyond the Pale: Frederick Douglass in Cork, The Irish Review (1986-), No. 24, pp 80-95, Cork University Press, 1999.

Fenton, Laurence. Frederick Douglass In Ireland: ‘The Black O’Connell’, Cork; The Collins Press, 2014.

Douglass, Frederick. My Bondage and My Freedom. Part I.--Life as a Slave. Part II.--Life as a Freeman. New York and Auburn, Miller, Orton & Mulligan, 1855.

Electronic Edition https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/douglass55/douglass55.html

Douglass, Frederick. Letters to Antislavery Workers and Agencies [Part 1]

The Journal of Negro History, Oct. 1925, Vol. 10, No. 4 (Oct. 1925), pp. 648-676,

The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History.

Brosnahan, James and Van DeMortel, Dan. Frederick Douglass travels 'home' to Ireland. Irish Echo, February 10 2021. https://www.irishecho.com/2021/2/frederick-douglass-travels-home-to-ireland

Douglass, Frederick. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (originally published by The Anti-Slavery Office in 1845), New York, Penguin Books, 2014.

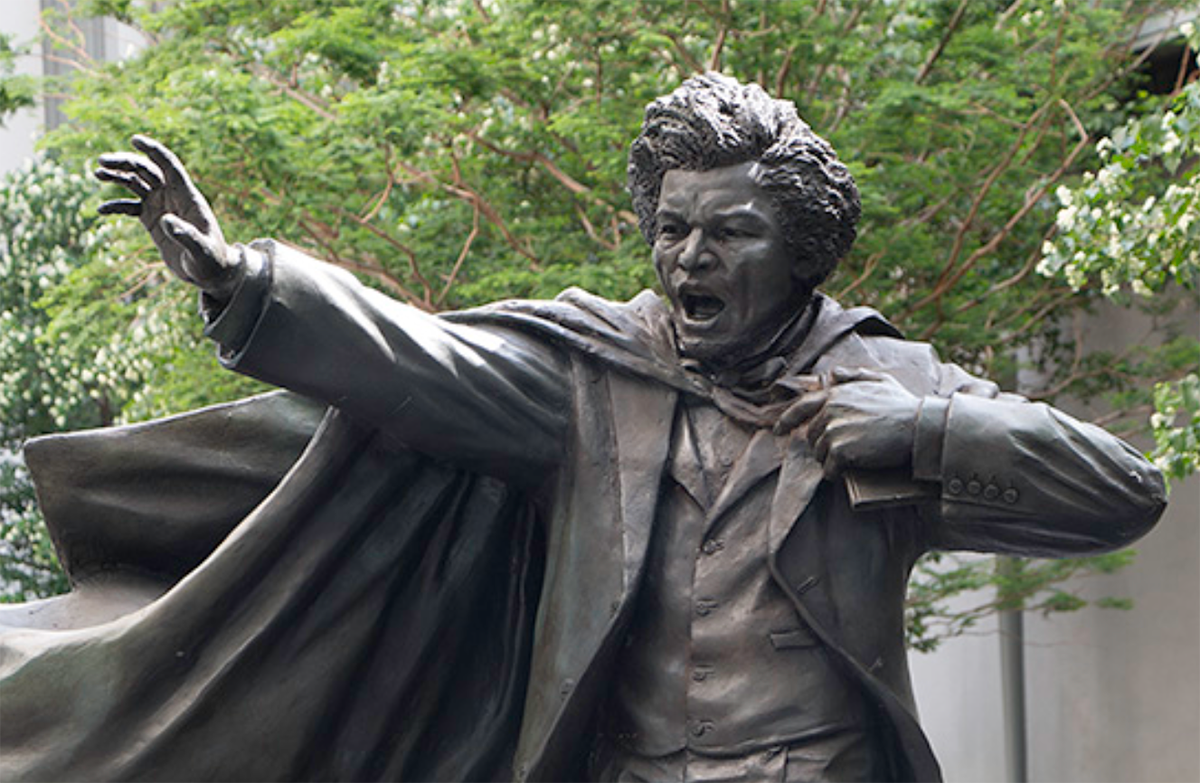

Top photo: The Frederick Douglass Ireland Monument, by Andrew Edwards. Photo by Society of U.S. Intellectual History.