Letter from the Editor:

The Ways We Value People

I’ve talked about my obsession with defining terms many times before. Always important (to me at least), it becomes critical when discussing things such as relationships, our commonalities and differences, and what we choose to value. Yet we all converse by throwing around words as if they mean the same thing to each other, when it often seems obvious to me they are very different things—and those differences can shape our worlds if we recognize them (or perhaps adversely if we do not).

When we debate romantic partnerships, for example, most of us realize that it’s hard to find another person who shares our values and wants the same basic things in life, even though we use terms such as “spouse,” “lover,” “partner,” or numerous others as if they’re one and the same. How does anyone ever find someone we can at least compromise with, day in and day out, about money, raising the children, which church to attend, how often to have sex, whose job matters most when geography is an issue, or Christmas at which parents’ house? Somehow, we all know that your idea of a “good” husband might well not be mine. (And all too often one’s own internal definition does not match the person to whom we’re married.)

Whom do you call a friend?

We often tend to put a whole lot of very dissimilar people into one common bucket and label it simply “friends” and, when we use this term with others, these people are given a bit of an elevated status—as if being X’s “friend” makes them a better person in some way. In reality, for many people, a “friend” is simply someone we’ve hung out with regularly or even possibly just on a handful of occasions, and about whom we know remarkably little.

Merriam-Webster, a frequent arbiter of such things, is, in fact, all over the place on the term: “A person who you like and enjoy being with; a person who helps or supports someone or something; one attached to another by affection or esteem; one that is not hostile; one that is of the same nation, party, or group.”

I am not in agreement with the ways in which people casually label so many others as friends, including Merriam-Webster; to me, the vast majority are mere acquaintances. “We’ve gone out for beers a few times.” “He was in my frat back in the day.” “I’m not sure of her last name, but she’s the cousin of my old co-worker.” “I’m not sure where we know each other from, but we’ve been Facebook friends forever.”

There are remarkably few people I define as a true friend. These are individuals I find to be one hundred percent honest and loyal, and who care about others as I do. People I’d go out of my way for because I can trust they’d go out of their way for me. People who show up not just for my parties, but my lowest lows. People with a whole helluva lot of mutual love and respect—and not just for me but for humanity overall.

This is not to suggest that they—or I—are perfect, or carbon copies of each other. My inner circle is beautifully imbued with people from numerous countries, in different shades, with different preferences and beliefs. As humans, I have seen them hurt others and sometimes even me, just as I have hurt others. The key difference is in their intent, and in their willingness to learn from their mistakes. I have seen them be racist or sexist or unfairly biased or just plain thoughtless, just as I and most of us have done some combination of these things from time to time. The people I value, though, appreciate being quietly corrected and then they do better.

If on occasion people acknowledged the core differences between these types of friends and those I call acquaintances, it would make the use of a common term more palatable. As it stands, too often people are unwilling or unable to discern one from the other. Sometimes they’re just very accepting, sometimes they get blindsided, sometimes they choose to believe that those who are “like them” in some overarching way must be good people (and sometimes, that those who are “different,” must therefore be bad).

It seems to me that life is too short to do less than give and expect the best, but I also understand that to a certain extent that is a luxury. I also understand that we value different things; while I find honesty and kindness to be the very foundation, others are content with a drinking partner. Does that make one more right than another? I suppose that’s a matter of opinion.

What is an ally?

To quote Merriam-Webster again, an ally is “one that is associated with another as a helper: a person or group that provides assistance and support in an ongoing effort, activity, or struggle”—and, more specifically, “often now used specifically of a person who is not a member of a marginalized or mistreated group but who expresses or gives support to that group.”

It sounds like a good way to be on the surface of things, and I admit that when the term came into vogue it was something to which I aspired.

As a child of the Civil Rights Era, I had this foolish notion when I was young that America’s problems with race and gender were being fixed. This notion was corrected in college—first when my Korean friends were shocked that I’d want to live with them, then seeing how other white folks responded, and finally by taking Black literature classes and having actual Black, Brown, and a generally wider assortment of friends.

I still had this crazy idea that our problems could be fixed within my lifetime, because people were innately good . . . weren’t they?! Love thy neighbor . . . do unto others . . . . The term “ally” had yet to be invented in the context of race and gender, so my Black friends were merely friends who I needed to support because that’s what friends do. Don’t they?!

After allyship became a thing, there was, as I mentioned above, a moment in which it seemed like a good group to identify with, a brief, shining moment in whiteness. (I can hear Black readers snorting in amusement and/or derision from afar!)

That was laid to rest during the “safety pin” escapades in which allies were to wear a safety pin in support of the vulnerable—Black and Brown folks, migrants, LGBTQ. Every liberal I knew started proudly pinning away, and it quickly became clear that for most of them, the pin was the thing: they weren’t necessarily well versed in what real support might look like and they certainly weren’t going to provide it. The pin made them feel good, not anybody who might have the need for an ally. Allies, then, were not real friends and truthfully not even acquaintances.

Clay and I actually debated the term extensively while working on the book Fieldnotes on Allyship, in which I likened the word “ally” to the many merit badges that are now given out in schools and on teams for simply existing. Like, “I’m an ally—love me.” Neither of us was fond of the term, although I still hadn’t quite put my finger on the core of my displeasure beyond the slipperiness of its users and its usage. Ultimately, we decided that we’d use it in the title simply because it was the most known and easily understood word choice.

I’ve moved still further from it more recently, as I’ve finally come to realize my biggest issue with “ally”: it’s the sense of dichotomy, or dare I say Othering. To be an ally to someone is to suggest that you are not the same—as in, the French are typically allies to Americans, but we are two separate nationalities. Now, Black people, Brown people, and white people are different shades, to be sure, but we’re different shades of the same thing (and similarly for gender and sexuality). One could argue that it’s simply the shade that is of relevance in allyship—it certainly is to the offender—but, unlike France and America, the very goal at the end of the day is to affirm our sameness.

Even further, there is a sense in allyship that one is doing something for the other, kind of like the white knight riding in on their trusty steed to save the day (and I apologize for the whiteness of that trope!). As if Black people, for example, are somehow needy or less than, and an ally is some beneficent being with a shiny halo. Being an ally is not something for which we white folks get a gold star; being an ally is helping to right a wrong of which we are in fact a part! (As white people, we all derive some value from our white privilege whether we choose to or not.)

I recognize that I might be overthinking this, but regardless “ally” is an important term. If white people want to be one, and appreciated as one, we must know what the term means and consider how far we’re willing to go. And, it’s something that requires commitment; one cannot do a good deed and check off a box.

Whom do you value?

I suppose that most OHF readers feel more similar to the way I do than otherwise on these matters. But it’s still important to reconsider the definitions from time to time and reevaluate not only what is important to you, but whether your friends/acquaintances/people you consider allies actually align with your expectations. Sometimes, as charming as a person might be, they are lacking in other important ways.

You can make exceptions for them (white people have more privilege in this area than Black people), but then you have to ask yourself: Are you having a positive influence on them? Or are they having a negative influence on you? (Can you perceive your values having changed over time in any sort of direct way? Do you act differently in their presence than otherwise?) How do others view you because of this relationship? In particular, do you have children who might be taking your relationship with this person as a lesson in values? Although my kids are not children anymore, I still see them silently absorbing and assessing the things that I do.

Some might also say I am overreacting; for some, this would certainly be the case. My own time has become more valuable as I’ve aged, and things that were acceptable when I was younger, no longer are. Although I’m hardly old as yet, I know better now what a day is worth, how I wish to be influenced, the mark I wish to leave. Do you?

In This Issue

- New This Week: “Frederick Douglass: An American in Ireland (Part I)” by Sylvia Wohlfarth

- In Case You Missed It: This week’s legacy article is “It’s Not About You. It Was Never About You.” by Erik Deckers

- Promo: OHF Magazine: The Baldwin Issue

- Final Thoughts

New This Week

Frederick Douglass: An American in Ireland (Part I)

by Sylvia Wohlfarth

The most celebrated Black man of his era, Frederick Douglass was also the most photographed American of any race in the 19th century. But what made him so unusual during his lifetime that elevated him so high in the eyes of the nation—and the world—that he lived in?

In Case You Missed It

It’s Not About You. It Was Never About You.

by Erik Deckers

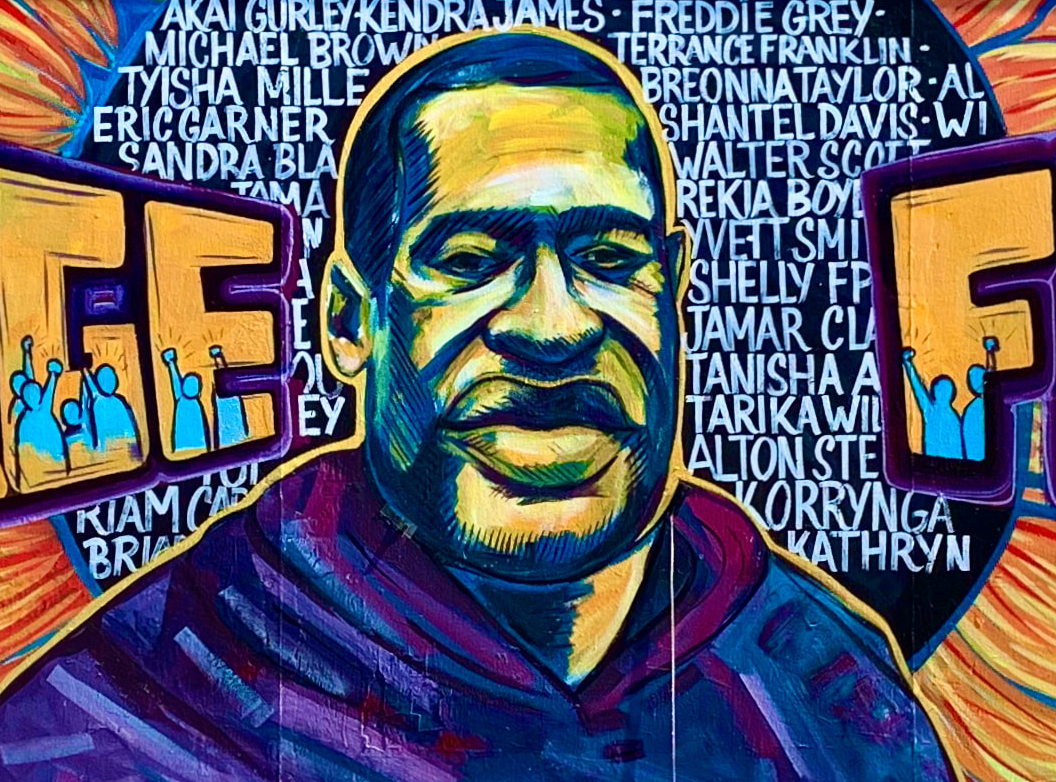

Why is it necessary to have special instructions for white people at the site where a white police officer murdered a Black man, setting off a tsunami of global protests? Because if you come into a space expecting to be recognized, you're missing the entire point.

OHF Magazine: The Baldwin Issue

James Baldwin, one of America’s foremost authors, activists, and playwrights, who addressed the themes of race, the political promise and peril of America, and the human condition, is the muse of this issue of OHF Magazine. We planned that Baldwin would be the muse for this issue back in fall/winter 2019, unaware of how prescient his words would be or the challenges we would face in 2021. And so in this magazine, we offer you interpretations of James Baldwin’s wisdom from the past written by people of different backgrounds and experiences who live their lives committed to justice, equality, and love as the proper means of moving into the future together in our human family.

Final Thoughts

Love one another.

Sherry Kappel

Our Human Family, Managing Editor

Top photo by marianne bos on Unsplash

Member discussion