It’s that time of year again when schools across the country trot out the five or six Black history figures whose stories have been shrunken and narrowed down to fit this country’s safe version of what Black history should be. But there were countless other African Americans whose contributions are worth sharing. And those choice few who made the “safe” list have more to their stories and lives than the accomplishments that were cherry-picked to teach school children during Black History Month.

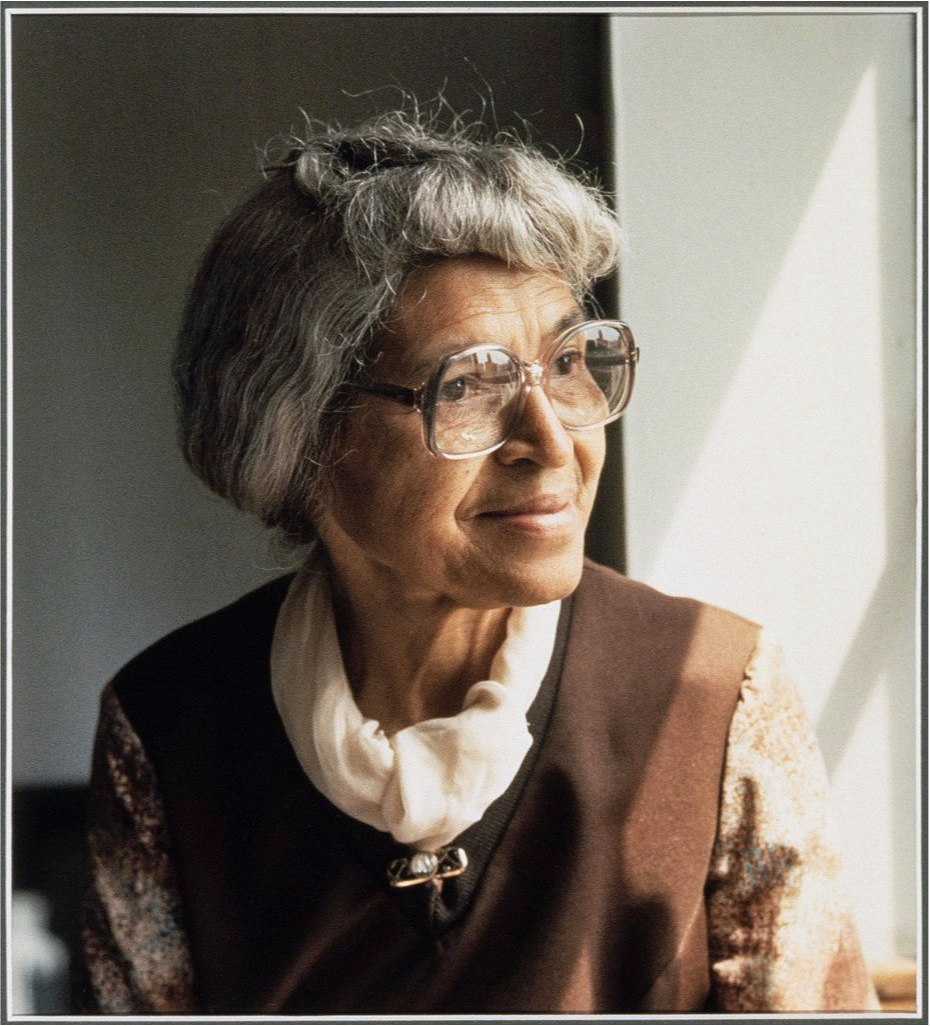

Rosa Parks, whose birthday happens to fall in Black History Month on February 4th (along with our awesome founder Clay Rivers), is one who makes the list each year as we are told how she was too tired to relinquish her seat to a white patron and so started a movement. But there was much more to Mrs. Parks’ story than just that one moment of tired defiance.

Life Before the Bus Incident

Long before Rosa Parks decided she was tired of the status quo, she was a young girl born in Tuskegee, Alabama to a carpenter father and schoolteacher mother. Her mother, Leona McCauley, would be her first teacher, homeschooling Rosa until she turned eleven. She was then sent to get a formal education at the Montgomery Industrial School for Girls.

This was a school started by two white Christian women, Alice White and H. Margaret Beard, who wanted to “provide an education as well as a sense of pride to their students during a time of racial segregation and to produce teachers who would go on to inspire others” (Harmon, 2007). In her autobiography Rosa Parks: My Story, she credits Alice White, the school’s founder and principal, with shaping her sense of self: “I was a person with dignity and self-respect who should not set my sights lower than anyone else because I was Black.” There were many other notable African American women who attended that school who would later go on to affect change both during and after the civil rights movement.

Included among the alumni were Johnnie Carr, Erna Dungee Allen, and Mahala Dickerson, Alabama’s first African American female attorney. According to the Encyclopedia of Alabama, Alice White followed Booker T. Washington’s educational program of industrial studies with a focus on self-improvement and made a point to also include rigorous academic training as well—everything Black girls would need to prepare them for the challenges of a racist and segregated country.

After leaving the Montgomery Industrial School for Girls, Parks continued her education at Alabama State Teachers College High School but had to leave before finishing to care for her ailing grandmother. She would eventually go back and get her diploma with the support of her husband, Raymond Parks.

Finding Purpose in the NAACP

Rosa married Raymond Parks in 1932. He was a barber and member of the Montgomery chapter of the NAACP. He encouraged Rosa to get involved as well, and she began helping to collect money for the defense of the Scottsboro Boys, nine African American teenagers falsely accused of raping two white women while riding on a freight train. Soon after that, she landed a job as secretary of the chapter.

As secretary, she investigated crimes against African American women such as rapes and assaults. Most notably, she helped organize the Committee for Equal Justice after investigating the brutal gang rape of Recy Taylor by six white men and then witnessing those men walk away from the crime without consequences. Alongside E. D. Nixon, a civil rights advocate and former president of the Montgomery NAACP, Parks was assigned with the duties of traveling throughout Alabama to interview witnesses to lynchings, victims of discriminations, and police brutality in an effort to help them fight against those injustices that African Americans faced every day.

Busy as ever, Parks also founded the Montgomery NAACP Youth Council to train young African Americans on how to challenge the systems of segregation and oppression they faced. Fun fact: it was Rosa Parks’ Youth Council that laid the groundwork for Claudette Colvin, a fifteen-year-old high school student who refused to give up her seat on the bus for a white patron even after the bus driver threatened to call the police. Colvin was arrested for her defiant act some nine months before Rosa Parks. Her arrest created an outrage in the African American community.

This would prompt civil rights leaders to seriously begin planning to boycott the bus systems. E.D. Nixon, a lead organizer of the boycotts along with others, decided that fifteen-year-old Colvin was too young and too pregnant to appeal to “the more conservative social mores of the times.” Clovin’s arrest did lead to a legal challenge, along with three other African American women, Aurelia Browder, Susie McDonald, and Mary Louise Smith, who were plaintiffs in Browder v. Gayle. Attorney Fred Gray filed a federal lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of Montgomery and Alabama bus segregation laws. Colvin and the three other ladies won the case which led to the end of Montgomery’s segregated bus system.

The Bus and Beyond

Nine months after Colvin was arrested for refusing to give up her bus seat, Rosa Parks would make the same decision. She reported that it was Emmett Till’s vicious murder and his killers walking free that sparked the fire in her to act that day. After seeing the vicious savagery of his killers, I could understand the need to strike back in some way against that type of hate.

As a kid, I read in my schoolbooks that she was tired that day, which is why she didn’t give up her seat. Framing her actions in that way took away the power and meaning behind it and that was the purpose of it. To conjure images of her as an old and frail woman tired after a long workday and bogged down with bags. But that wasn’t her at all.

Parks declares her defiance was an intentional act: “I was not tired physically, or no more tired than I usually was at the end of a working day. I was not old, although some people have an image of me as being old then. I was forty-two. No, the only tired I was, was tired of giving in.” She made a conscious decision that enough was enough, and when she was arrested E. D. Nixon had found the perfect face for the movement.

Nixon recalled: “When Rosa Parks was arrested, I thought ‘this is it!’ ’Cause she’s morally clean, she’s reliable, nobody had nothing on her, she had the courage of her convictions.” Parks could not be shamed or exposed, and she had a motherly air about her such that African Americans would be appalled at the sight of her sitting in a jail cell. Nixon was correct in his assumption and began planning immediately.

For all the positive attention that her refusal brought and the changes it would eventually set in motion, there were plenty of negative consequences, too. As if sitting in a dirty jail wasn't bad enough, Parks and her husband began getting death threats. Parks lost her job as a seamstress and her husband lost his job as a barber at an Air Force base for his refusal to be silenced about his wife’s legal case. According to the NAACP website, Parks began supporting the more militant activists and thought the slow and steady way to equality wasn’t the best route moving forward. This disagreement of minds was another factor that prompted the family to have to move for both safety and financial concerns.

The couple ended up in Detroit, Michigan, where Parks found that the conditions were not much different. So she knew she needed to get back to work.

In Detroit, Parks began advocating for fair housing and supporting local African American politicians. She aided John Conyers in his bid to gain a seat in Congress. After his election, Conyers made Parks his secretary. Seeing how the younger generations of activists were becoming more militant inspired Parks, and she set out to work with these young people who had grown tired and weary of the nonviolent, peaceful approach that was slow to make progress. In a 1973 letter on display at the Afro-American Museum, Parks explains how they felt:

The attempt to solve our racial problems nonviolently was discredited in the eyes of many by the hardcore segregationists who met peaceful demonstrations with countless acts of violence and bloodshed. Time is running out for a peaceful solution. It may even be too late to save our society from total destruction.

Parks has also shared that she considered Malcolm X her hero and she was in tune with his “eye for an eye” approach. In her letters, she expresses the need to defend oneself should the need arise as opposed to turning the other cheek. She was a fighter and admired the fight in the new breed of activist who embraced that “put your hands on me and expect fists back” type of attitude. Wanting to continue to support and nurture young activists, Parks founded the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self-Development geared toward helping Detroit’s young people.

After she retired from her job as John Conyers’ secretary, she traveled the country attending events and speaking out about the issues that she had fought against for so many years—issues such as police brutality, voting discrimination, justice system reforms, and equality in housing and employment. It’s sad that for all her decades of fighting the good fight we are still struggling with police brutality, voting discrimination, housing and employment inequality, and a broken justice system, for although some things change, more things stay the same. And I repeated all those things because it bears repeating. The baton has been reluctantly passed to another generation.

A Life Well Lived

The end result of Rosa Parks’ years of putting her boots to the ground and doing the hard work to fight against white supremacy is a life well lived and well loved. There was more to her story than just refusing to relinquish a seat on the bus. Rosa Parks was a fighter for justice, tirelessly working on behalf of those crushed by the weight of white supremacy. Trying to lift that endless weight to give those suffering whatever relief, comfort, and assistance in their quest for justice and equality.

She has earned several awards, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Congressional Gold Medal, and the NAACP’s Springarn Medal. After her death, she was honored by Congress and the President by being the first woman to lie in honor at the Capitol Rotunda. The best way we can honor her this month and every month after is by continuing her legacy of standing and fighting against the oppression of white supremacy in all its ugly forms in whatever way we can.

Happy Birthday, Mrs. Parks!