I was brought up in a Christian home. All four of my grandparents (God rest their souls), my father (had), and my mother still has a palpable faith in God and a relationship with Christ. They had to. They were Black people living in the South. Their faith is my heritage. I accepted Christ as my savior when I was sixteen. Nothing made me happier knowing that one day I’d get to meet Jesus face to face.

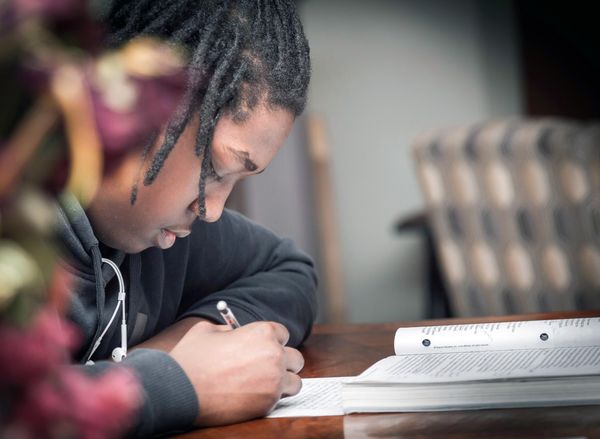

As early as elementary school, I knew that I preferred the company of my male classmates. In high school, the full definition of the term “fag” eluded me, but I knew enough to know that I didn’t want to receive the patent ostracism that accompanied the epithet. So I used my accomplishments in other areas—student government, yearbook, band, Honor Society, theater—as diversions and deflector shields to protect myself from a truth I was not ready to acknowledge.

The summer before I left Orlando for college, I experienced my first physical connection with another person I was attracted to. A guy. After the thrill of it waned, guilt and shame permeated every fiber of my being. If people didn’t look at me differently because of my height, surely they knew the source of my shame. How could they not know? And since God already knew . . . I was certain my salvation went out of the window with my first kiss.

For the next twenty-two years, I wrestled vigorously with reconciling my faith with my sexuality. I put God in a box as I explored what being gay meant. I re-discovered God in a non-denominational, Bible-based church, and learned via regular Bible studies that Christ’s love for me was far greater than I could begin to understand. I also learned that God was interested in all aspects of my life and that he revealed himself, as well as his will for me, through not only Scripture but friends, strangers, divine appointments, music . . . basically, anything he wanted. All I had to do was listen.

I tried therapy in an earnest and fervent attempt to facilitate changing my sexual orientation and went back into the closet in an attempt to no longer be gay. Lest you skeptics out there think I was half-heartedly dipping my toe into the water, know this: I wanted nothing more than to be straight and deemed acceptable by God and everyone else. I moved forward with the support of both my straight and gay friends . . . but after a few years, I came back out of the closet.

I moved to California shortly afterward and went on a spiritual journey in search of a faith that worked for me. Along the way, I tried Pentecostal churches, the Presbyterian church, but The Episcopal Church most resonated with me. Everything TEC stood for resonated with me. The liturgy, the beauty of the words, the vibrancy, the social activism, all of it.

But something wasn’t right. I hadn’t resolved the internal conflict of my faith and my sexuality, then subsequently slipped into a massive depression for several years.

One afternoon in Los Angeles while riding along the 110 freeway and listening to Focus on the Family, I learned that a specialist in reparative therapy had an office not even five miles from where I lived. I took it as a sign. A divine appointment, if you will. It was my opportunity to reconcile my faith and sexuality with the aid of an expert in the field.

After twenty-two years of searching and trying to make myself into what “I” thought everyone else, including God, wanted me to be, the Lord spoke to me in a manner that was uniquely his own. Perhaps he had been speaking the whole time and I wasn’t listening. But on the morning of September 30, everything aligned, and the epiphany tucked in the middle of that day’s devotion dropped me to my knees. It read—

‘Unless you become as little children . . . ’ The spiritual life might be defined as the development of personality in the realm of faith and grace. My Christian personality is not just a vegetative existence; I am a unique and radiant center of personal thought and feeling. Rather than living a routine existence in mere conformity with the crowd, the emerging child reminds me I have a face of my own, gives me the courage to be myself, protects me against being like everybody else, and calls forth that living, vibrant, magnificent image of Jesus Christ that is within me waiting only to unfold and be expressed.

—Brennan Manning, Reflections for Ragamuffins

How did I interpret that?

My life was a pilgrimage, a journey to grow in the knowledge of and experience in who God is. My life was also a journey of accepting myself, warts and all. Everything I have lived and experienced pointed to that conclusion. I was to be who I was. He had been delivering the same message to me that time and time again, and used countless people of all walks as his messengers.

My purpose was to strive to be all that God intended for me to be. Instead of this creation telling its potter how he should have made me, I was to realize that I am indeed the work of his hand. I was to embrace all my distinguishing characteristics and love myself and others the way he loves me, for purposes larger than my understanding.

And if that wasn’t enough, through my tears, I distinctly remember the Lord impressing one particularly precious thought upon me. And I know it was the Lord because I experienced the same feeling hours after my father died when riding in my car alone I asked no one in particular, how am I going to get through this? and the thought came to me, “Let me carry you through this.”

I felt compelled to respond, okay. I remember just being awash in peace and that everything was going to be all right. But the Father’s message to me was this, “I am more concerned about your relationship with me than I am with your sexuality.” And once again, I felt drenched in love, hope, joy, and peace.

For me, as a gay Christian man—someone who has wrestled with reconciling my faith, my sexual orientation, and the expression of both—the matter has and will always be about this: how do I account for how I lived my life before Christ?

My relationship with the triune God is everything to me. As a four-foot-tall, black, gay Christian (you think that’s tough saying, try living it), my faith is what makes it possible for me to wake up and face the world with all of its challenges. I’ll tell you about a few of those another time.

My sexual orientation is not my identity. It is only a part of who I am. It colors how I relate to people of both sexes, and those intersexed. But despite or because of my combination of traits, I like to think God has been able to bring forth some “goods” in my life . . . otherwise, I wouldn’t know the joy of serving God and his church in so many ways.

I’ve been blessed to have been raised in a Christian family and home. I have the honor of having clergy, their spouses, and families as my closest friends. I have been blessed with friends who strive to live out Christ’s teachings. But there are so many people who haven’t had the benefit of being raised in a Christian home or have years of studying scripture or have been damaged by the church.

A number of them are gay.

If an LGBTQ person is making the effort to visit a church, especially given most denominations’ active and passive unwelcoming of LGBTQ people, chances are they’re knowingly risking ostracism as their search for Jesus is their first priority. But some decline invitations to the Lord’s table because of the church’s reputation in its treatment of LGBTQ people. In short, they have no use for the church. And how sad is that if we who lay claim to all that is good can not be emissaries of Christ’s love as he commands?

My question to priests, theologians, and the laity is this: how will you demonstrate Christ’s new commandment to love one another as he has loved us when you encounter those you consider “other”?

Love one another.