“You experience them experiencing pure magic, unadulterated by cynicism or irony or self-consciousness. And as the ride makes its full circle, so do you, until Peter Pan has done it again, and you are once more a child, taking it all in, amazed, overwhelmed, enchanted.”

―Neil Patrick Harris, Choose Your Own Autobiography

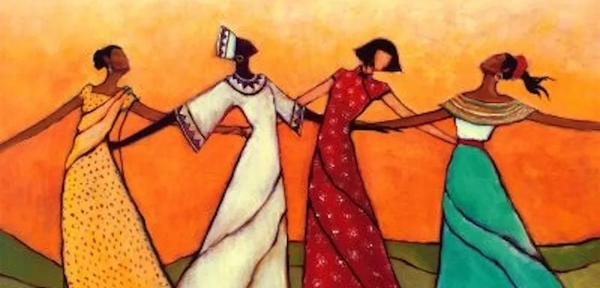

There are few things closer to universal than the desire to settle into one’s existence with a loving mate and children. It’s partly biological, but it’s also much, much more and it crosses all cultural, geographic, demographic, social, and economic strata. I’ve known quite a few people who swore they were different, only to change their minds when the proverbial clock started ticking and fall crazy in love with their new little bundle. And even those who decide that parenthood isn’t for them, are typically thrilled for friends who do and happy to serve as “aunt” or “uncle.”

Although I straddled the fence beforehand, I can verify that my children are easily the most important part of my pretty good life. It’s not something I can quantify beyond a feeling deeper than the ocean and higher than the stars. So when my friends decide to have children, I am joyful for them—and when they struggle to make it a reality, my heart hurts for them.

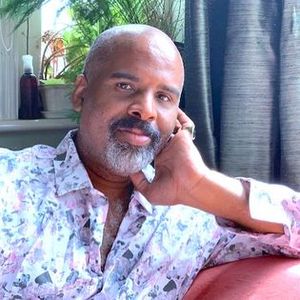

My friend Ryan is one of my favorite people in the world (don’t tell him!): tall and handsome, super smart, insanely funny, creative, talented, and—what matters most—one of those few people in life who always understands and is always there for his friends. I knew from the minute I met him that he had the heart, the passion, the patience and kindness, and the wisdom to be an excellent father. I also knew that he’d struggle to reach that point because Ryan is gay.

Ryan is happily married, but his world really begins and ends with his son Jordan. Every joke, every story, even the new tattoo that is a perfect replica of seven-year-old Jordan’s latest artistry. And we, his many friends, melt like a popsicle on a summer sidewalk with each telling, because we know what it took to get this far. He is perhaps at his most “fatherly” though, when Jordan misbehaves—and Jordan definitely has a mischievous streak.

Ryan laughs a touch ruefully as he talks about Jordan’s recent “Big Adventure”—also known as, the red paint incident.

He explains that it is the second graders’ job to make it on their own from their classroom at the end of the day to another room where they walk down to aftercare as a group. (I immediately sense a few issues in this scenario!) One day Jordan started down the hall with a friend, and apparently his friend was very sad about something. Jordan decided to cheer him up by taking him on an adventure, pulling him into the empty art room.

It began with red paint. Lots of red paint. Everywhere. In their hair, down their faces, up and down their bodies. It filled up their ear canals! I can imagine it flying through the air. I try not to laugh. At some point, they mixed it with clay—lots of clay—and began to paint the walls. Ryan, both neat and artistic, is horrified even in the telling.

Fortunately or unfortunately, the art teacher returned for something she’d forgotten, and the party came to an abrupt end.

Ryan is in full disciplinary dad mode just thinking about it. “Jordan’s too old to act this way. This was not how he was raised—he knows better!”

Yet part of him is also in classic protective dad mode. “They had no idea he was even missing before that; if it weren’t for the art teacher coming back, I could have shown up to get him after work and they’d have had no idea he was gone. He could have been anywhere!”

Ironically, while the school’s first response was to make Jordan sit in the middle of aftercare covered in paint and not move while the other kids ran around him, their response to Ryan’s queries about punishing him was to shrug and say, “Boys will be boys.” Ryan had to talk them into a month of in-school suspension—“and they only had him clean the art room for an hour. How is he supposed to learn from it if there aren’t consequences?!”

I had to ask: “Did you not laugh about this at any point?”

Ryan finally grins like the laid-back guy I’ve always known outside of fatherhood. “Not until he was asleep that night. I can’t tell you how long it took to get the paint off of him. But seriously — what was he thinking!”

For the average male and female couple, making a baby is usually a fun, easy process. And, it is almost always problematic for members of the gay community, but no less of a major life goal. Most of my gay friends in committed relationships, including Ryan, were elated when they were finally able to legally marry—and then felt the need to jump immediately into the tangled issue of procreation. Unlike straight couples who have the luxury of insisting on sharing their genes, most gay couples tend to be open to any means possible. Sonograms and first heartbeats are a privilege they can’t count on.

There are jokes about lesbians and turkey basters, but I can attest to a pair of my friends’ daughters being conceived that way—not so quick nor simple as it sounds. Even harder is the question of finding a sperm donor: is a friend or family member willing? What will that be like growing up? What are the legal ramifications? It’s a tough enough road that I feared for a time it would be too much for this otherwise loving and devoted couple.

For gay men, it is harder still. Even assuming they can find a spare womb and withstand the emotional ups and downs of nine months of surrogacy, more than a few times the woman has found that she couldn’t go through with giving up the child, crushing the fathers’ dreams. Until the past couple of decades, surrogacy wasn’t a legal option for anyone; as it stands now, the laws are still spotty and troublesome, particularly for gay couples whose rights are tenuous anyway. My friend Ryan has his own story about surrogacy.

The plan seemed simple and was a win-win for everyone involved. A very close friend and her partner wanted a child, as did Ryan and his husband Sydney. They would have two children, with Ryan fathering and the friend carrying them. But — the babies would be biological siblings. Would that be weird? Were there legal issues? What if, God forbid, something was to happen to one set of parents? Ryan felt it might be best if the child he and Sydney were to keep would come from a donated egg, but his friend didn’t like the idea.

They went back and forth on this and other questions, debating long and hard until they were all ready to finalize, and Ryan and Sydney were thrilled and relieved to know that their wish for a child was finally reaching fruition. And then — nothing. Silence. The friend simply stopped taking their calls. They never talked again.

“We were devastated,” Ryan confides. “To get so close . . . and we lost not only a child but a good friend.” He hadn’t shared his plans at the time and the pain is still very evident now. Yet I suspect that they might have dodged a bullet, as well. Dreams are fraught with unexpected twists and turns, but especially when you’re gay in America.

Ryan is a laid-back guy with a great sense of humor to help him maneuver through life; he’s also shy and cautious. Having struggled through a strict Catholic upbringing that suggested he was an abomination, plus demanded marriage to a woman, he waited to come out until his thirties—shortly after I met him. Even then it was tough emotionally, and he did it in stages, slowly building up the courage to tell his parents. Fortunately, unlike the response to many gays even today, most of his friends and family were understanding. (I am quite certain there were more bumps in the road than he’s let on—he is relentlessly upbeat).

All of that finally settled, he wanted little more than to quietly live out the quintessential American dream of a happy marriage, a house in the ’burbs, and two kids in the yard. Gay marriage was not yet legal when he met Sydney, but history was on their side: they had to wait a little bit, then they had to travel out of state, but they were ecstatic to trade rings in a small, private ceremony. The kids would turn out to be a much longer process.

Ryan would have you believe that the journey from then to Jordan to today, while long and with the occasional hiccup, was relatively painless. Issues are to be expected in such things. That’s just who he is, but I know better.

Beleaguered and losing hope after their friend/surrogate mother abandoned them, the couple placed a last-ditch call to the local LGBTQ center—a resource Ryan acknowledges that many gays don’t have at their fingertips. It seemed a long shot, but as he notes, “Where do you go? Who can you trust?” Ironically, the director of the center had just adopted a child of his own and highly recommended the agency he’d used. He gave Ryan the name.

Ryan would have people believe that the journey from then to Jordan to today, while long and with the occasional hiccup, was relatively painless. Issues are to be expected in such things. That’s just who he is, but I know better. I heard the tone of despair along the way. It takes a lot to get that from him. I learned not to ask every time we talked.

Adoption can be bumpy and seemingly impossible, but even more so for a gay couple. For starters, it’s illegal in our state; in fact, our kind legislators wrote it into our constitution in 2012. Private adoptions happen but are prohibitively costly and still uncertain. The workaround is to foster children and hope one of them eventually becomes permanent. But even then, as Ryan noted in his blog at the time, “only one of us can adopt the child/ren, the other has to be protected with legal loopholes, living wills, etc. Ridiculous, but you do what you have to.” (Luckily a federal judge ruled that unconstitutional before they completed their adoption.)

Ryan and Sydney pressed onward. They thought it would be a relatively quick process—it was not. Before you can even meet a kid, there are two and a half months of parenting classes three times a week, a CPR class, thirty-two pages of questions apiece, and essays. I wrote a letter of recommendation, I’m sure numerous others did, as well. We helped them fill a room with kid stuff because, once you’re approved, you can theoretically get a child at a moment’s notice. No one is approved until the space is ready. There were fingerprints and background checks, medical checks, house checks, fire inspections. Interviews, reports, and responses.

Whoever has said that just about anybody can be a foster parent has not been through the system. As Ryan puts it, “They get really into your business.” Ever the optimist, he calls it “a good opportunity to work through your own issues.” Are straight and gay couples treated similarly? I have my suspicions. The parenting class talked only about “traditional families”; still, Ryan swears the agency showed no discrimination throughout the process and the social workers were all nice. Social work is a tough profession, and good foster families can be hard to come by. Yet it would take a year before Ryan and Sydney actually met any children.

Within a few breaths, Ryan and Sydney went from being the only family in consideration to one among “other options.”

Once Ryan and Sydney were finally approved, they would receive information from time to time about a variety of kids they could pick and choose from. After they made their selections, the agency would decide which ones they thought were a good fit. Ryan points out that there are “regular” and “therapy” homes, with the latter better prepared for children with issues. They had no experience with troubled kids and were not approved for them.

Nonetheless, one of the two brothers they were handed clearly needed more help than they could give; among other things, they’d wake in the night to find him beside the bed, just staring down at them. Their bio mom referred to Ryan and Sydney as Chuck and Larry from a movie about two guys pretending to be gay. The brothers went back after a couple of weeks.

Another boy, a twenty-two-month-old Black toddler, seemed like a perfect fit to everyone involved: Ryan and Sydney, the social workers, and the child’s family who wanted to stay involved with him. Ryan arrived to meet everyone before Sydney could get there, and thought it was going great. Then Sydney showed up, and there was some confusion. Sydney was not a woman? Within a few breaths, Ryan and Sydney went from being the only family in consideration to one among “other options.” Ryan says they almost gave up completely at that point. His blog grew quiet. We stopped asking at all.

They looked at other kids though, there were other issues, they persevered—and then they finally met Jordan, who lived several hours away. At five, Jordan had been in and out of foster care for a while. He didn’t enunciate well, he had a limited vocabulary, but he was super friendly and outgoing; he was a favorite among the social workers and they wanted him to be placed well at long last.

Ryan and Sydney took Jordan to a nearby children’s museum for the afternoon, then got him for a whole day the next time, a weekend at the hotel after that. Ryan says they truly just gelled immediately: “It was so cool.” He glows just remembering. Next Jordan came to their house for a holiday weekend. When the social worker picked up Jordan on Monday, they inquired as to the following weekend and were told simply, “He’s moving in with you on Thursday.”

My eyes are welling up just typing that. His eyes welled up talking about it. I know many wonderful parents, but none that are more deserving—or who went through so much to get there. And even though I’d been along for a bit of the ride, he’d skipped the less happy details.

Fast forward a couple of years to the school scene. Ryan, Sydney, and Jordan have thoroughly bonded and are a “forever family” now, but it hasn’t been without challenges. Because they had to go through the foster system, it took seventeen months of court battles against his birth mom before the adoption was permanent (she is now in jail, likely for life). Although there was little doubt they’d win, it still wears on a person. And, after an initial month of perfection together, Jordan started acting out and threatening to leave; with five years of instability, he was determined to be preemptive about their eventual rejection. They finally sat him down and explained that there was nothing he could do that would make them not want him — forever is forever. He settled in. I see him on Facebook now dancing, twirling, and smiling every other day.

Although the path to parenthood probably took them close to five years in all, Ryan acknowledges that their struggle was undoubtedly easier than for most gay men. He and Sydney are white, well-educated professionals living in a moderately liberal urban area and have some financial resources. They have friends and family supporting them. “But Jesus, Mary, and Joseph,” he jokes on his blog, “it sure would have been a lot easier to knock up a lady-friend the old-fashioned way.”

Now, of course, they and the entire gay community are nervously watching their young and fragile LGBTQ rights being stripped away in America’s alt-right political climate. Sydney is increasingly angry. Ryan is trying not to stress, instead focusing on the crazy, frenetic joy that is Jordan, while starting the process to find their son a sibling—perhaps quicker in round two, but certainly another year or more and assuming the laws don’t worsen.

I watch the news, and I worry for them.