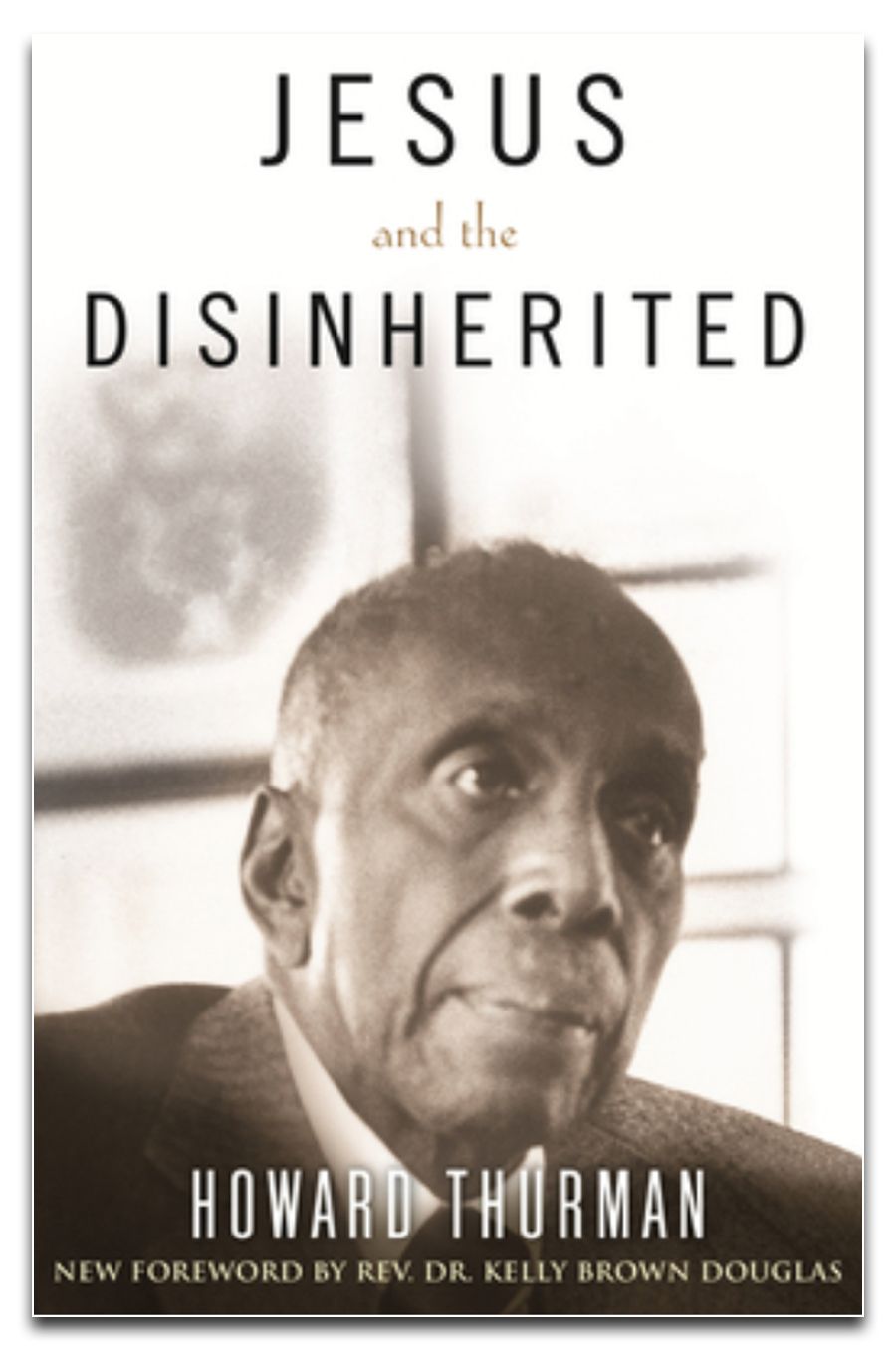

It’s said that the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. carried a copy of Howard Thurman’s seminal book Jesus and the Disinherited on his travels. “Considering the generations-long relationships between the King and Thurman families, Martin likely had the message of these pages etched on his heart,” writes Vincent Harding in the book’s forward.

Hidden in the book’s title is the question haunting the history of the Christian faith in America.

I’ll get to that question in a minute.

But first, I had to find out who Thurman was, and why his line of thought felt so familiar. I doubt it was because he was born in Daytona Beach, Florida, only an hour’s drive from where I would be born 72 years later. How different our lives have been!

Thurman was raised by his grandmother, who was born into enslavement on a Florida plantation. He was greatly influenced by her experiences and deep Christian faith, a fan of Jesus though not of St. Paul. Forced to work on the plantation, several times a year she heard “the master’s minister use [Paul’s letter] as a text . . . ‘Slaves, be obedient to your masters.’ Then he would go on to show how it was God’s will that we were slaves and how, if we were good and happy slaves, God would bless us. I promised my Maker that if I ever learned to read and if freedom ever came, I would not read that part of the Bible.”

She eventually did find freedom and therein raised her grandson, Howard Thurman. Soon enough, he traveled to one of the few high schools for African Americans in Jacksonville before going to Atlanta. There he graduated as valedictorian from Morehouse College in 1923, where he was a classmate and friend to MLK Sr., well before MLK Jr. would be born and eventually attend. Thurman would go on to teach at Morehouse before leaving for Howard University, and eventually to Boston University where he became “the first Black dean of a chapel at a majority-white university in the U.S.” In between he co-pastored the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples alongside a white minister, creating what many say was the first racially integrated church in the nation.

When I read a book, my eyes are usually darting around the pages looking for some connection — perhaps for some form of myself to appear on its pages. (I trust I am merely verbalizing a universal behavior and am not a specifically narcissistic reader). In recent years, I’ve set out to read books where I don’t readily appear — at least not at the center — to better understand what this world looks like from other points of view.

In Jesus and the Disinherited, Thurman quickly bypasses my entitled question Where do I fit into this story? in favor of a more noble one: Where does Jesus fit into this story? The story he’s describing is that of the disinherited, which he defines as “those who stand, at a moment in human history, with their backs against the wall.” But the central question is whether the gospel of Jesus has anything of value to give to them. Sure, there’s the promise of an afterlife, but what about now?

Now, the “‘religion of Jesus’ and its strange mutation, American Christianity,” as Harding phrases it, are two different things. The book wrestles with these two faces of Christianity: the one that invites and cares for society’s vulnerable, and the one to which they are vulnerable. “Too often the price exacted by society for security and respectability is that the Christian movement in its formal expression must be on the side of the strong against the weak.”

To press further in, consider this difficult question along with me, that Thurman poses in the preface:

“Why is it that Christianity seems impotent to deal radically, and therefore effectively, with the issues of discrimination and injustice on the bases of race, religion, and national origin? Is this impotency due to a betrayal of the genius of the religion, or is it due to a basic weakness in the religion itself?” –Howard Thurman, Jesus and the Disinherited.

To begin answering this, Thurman first sets out to ask who Jesus of Nazareth is, then through the remaining chapters comes back to the question of what that Jesus can offer those with their backs against the wall.

As for Jesus, Thurman considers what the young Jesus saw and felt growing up in first-century Palestine, as a Jew under Roman rule. Surely he was shaped by the fear surrounding him and the feeling of powerlessness behind his Jewish peers’ desire to rise up and be free. Whatever part of Jesus was fully human would have fully understood the struggle to survive physical and political poverty.

Divinity aside, Jesus held very little power in society. In fact, he provoked those in religious — and apparently political — power, given that both factions teamed up to kill him. His earthly ministry as seen in the four gospels would likely be criticized as wasteful by ecclesiastical strategists: healing the outcasts of society, conversing across gender and ethnic lines, confronting the clergy yet granting salvation to a dying criminal. How would that approach ever go viral?

. . . in today’s pluralistic America, the dominant group is more like the powerful Palestinian Romans than the first century Jews

It’s hard to find any reading of Jesus’ teachings in the New Testament as encouraging his followers to take and maintain political or social power. And yet, that’s exactly what has happened over the centuries, up to and including today. (This may be difficult to see for frogs like me who have always boiled in the pot of a white “Christian” society: that in today’s pluralistic America, the dominant group is more like the powerful Palestinian Romans than the first century Jews; yet somehow many Christians have developed what Rachel Held Evans called “an overwrought persecution complex that confuses sharing civil rights with others with being persecuted by them.”)

Thurman writes, “This is a matter of tremendous significance, for it reveals to what extent a religion that was born of a people acquainted with persecution and suffering has become the cornerstone of a civilization and of nations whose very position in modern life has too often been secured by a ruthless use of power applied to weak and defenseless peoples.”

One of history’s most astounding miracles is that the Black American church even exists, given the setting in which Jesus’ message was heard by its founders. And yet it doesn’t take much of a stretch to see Thurman’s early twentieth-century connection between “the social position of Jesus in Palestine and that of the vast majority of American Negroes . . . We are dealing here with the conditions that produce essentially the same psychology.” From that view then, it absolutely makes sense that the Black church would thrive — misused Pauline quotes aside — but then it would also seem a natural outcome that the white sections of the church would defer to its Black members as mentors.

But Thurman’s short book is not about browbeating. He is interested more in the soul and psyche of the disinherited — how they view and value themselves — and what Jesus of Nazareth can offer that view.

And this is where he takes the rest of the book. Working through responses to the three “hounds of hell”—Fear, Deception, & Hate—he asks, and nearly answers, what difference does this Jesus make to the seemingly disinherited souls of the world? (The topic is never limited to one culture, with mentions of “Untouchables in Hindu lands,” Asian Americans, “Jewish ghettos,” and many other people groups whose names may have changed since the time of the book’s writing but whose situation hasn’t.)

. . . if a man continues to call a good thing bad [or, I would add, a bad thing good], he will eventually lose his sense of moral distinctions.

One chapter discusses the effects of fear on the disadvantaged and advantaged alike. What are the options for a person who is wronged by society — where even systematic slights play out in a very daily and personal way? “The disadvantaged man knows that in any conflict he must deal not only with the particular individual involved but also with the entire group, then or later. Even recourse to the arbitration of law tends to be avoided because of the fear that the interpretations of law will be biased on the side of the dominant group.”

In the chapter on deception, he considers three answers as to whether one should value their own safety over speaking honestly. In such a society, if deception is assumed by both the advantaged and disadvantaged, haven’t both lost their moral compass? “It is a simple fact of psychology that if a man calls a lie the truth, he tampers dangerously with his value judgments.” Thurman goes on to quote Jesus’ example, when accused of being of the devil, that “A house . . . divided against itself . . . cannot stand.” “That is to say, if a man continues to call a good thing bad [or, I would add, a bad thing good], he will eventually lose his sense of moral distinctions.”

Thurman concludes that Jesus teaches all to keep our moral integrity and hold our heads up. But not without considering this: When the message is keep your head down and your hands visible — a message Black parents are still giving their kids today in preparation for police encounters — how does that affect the thoughts inside the head? What happens to the inner anger, how does one feel when fighting back is not an option? “There is but a step from being despised to despising oneself.”

Reading these sections feels to me like listening into another family’s meeting (if I’m still allowed to ask where I fit into this story). Like a “Big Brother” mentor, he incisively builds an argument of hope for those who fear defeat based on odds they cannot control, whose crucial questions are: Who am I? What am I? Perhaps like life’s other big questions, I cannot capture his eloquence here but will return to it again and again seeking to find its meaning.

I’m clearly not his audience: “What the religion of Jesus suggests to those who would be helpful to the disinherited . . . is utterly beside the point to examine here.” Nonetheless, hearing what the wall looks like from another social location is deeply affecting. Why is the wall still there? Am I doing anything to reinforce it — or to ask more aggressively, am I doing anything to dismantle it?

And regardless of our proximity to Thurman’s metaphorical wall, once we bend our moral standards for or against one group of people, we open the inner passageways in a way that cannot be easily contained. “The logic of the strong-weak relationship is to place all moral judgment of behavior out of bounds.”

Thurman’s chapter on hatred claims the effects of hatred are devastating to the moral compass of both the hater and the hated.

The fear inspired in the disadvantaged boomerangs to breed fear among the advantaged as well, fearing an uprising or worse: the need for the advantaged to change, to share, to listen.

Thurman’s chapter on hatred claims the effects of hatred are devastating to the moral compass of both the hater and the hated. Perhaps you’ve tuned out here because you don’t hate, you don’t fear, you don’t plan to deceive. He is talking directly to his own extended family about how to handle the hatred they feel in being oppressed. But how convicting it is to read this calling to take the moral high road given to those who had been forcibly placed onto society’s low road!

I wish I could better communicate the joy, and the challenge, of summarizing these one hundred pages of beauty — if truth itself is beautiful — to you. But I simply recommend you read it yourself. In the end, it may seem familiar to you, too, and that may likely be because it has so profoundly influenced much of what you’ve heard Martin Luther King, Jr. say.

Or maybe it’s because both King and Thurman had a common source for their views, and sought out that source on behalf of those under his care living under the religion formed in his name.