On April 27, 2023, Emmett Till’s last living killer died.

Carolyn Bryant was the lone custodian of America’s taut and bubbled scars — scars that Bryant herself helped beat into the nation’s back, and across her buttocks and thighs. Will those wounds finally begin to quiet, soothed by the cool, dark dirt of her grave?

To be clear, the bloodlust for justice will never calm, and the rage hunt never slows. These are things that sunset only when time does, and not so much as a millisecond sooner. The complicit still move among us. For them, there will be no quarter and no peace. From the beginning, these things must be clear.

But whether we, each in our own private way, can calm our hearts is a different sort of question. A battle-weary warrior teaches that some rage must roil, and others must go quiet, as not all can occupy first position; that this necessary but fatal weapon kills well, but it also kills indiscriminately; that we harness that tool and use discretion to protect both warrior and mission.

And so, does the death of the Maven of Hate leave room to wave off this poison?

Perhaps. Knowing whether karma ever caught up with Emmett Till’s killers would certainly help with that answer.

The Emmett Till story is a familiar one.

In 1955, Carolyn Bryant falsely accused fourteen-year-old Emmett Till of catcalling. Her husband, Roy Bryant Sr., and brother-in-law, J. W. Milam, kidnapped young Till in response. Well into the night did those two men beat him. They beat him so badly, in fact, one of his eyes popped from its socket.

Milam forced Till to strip, and one by one, the child removed his socks, shoes, shirt, pants, and undershorts until he stood before the men—naked. They were never able to scare Emmett, Milam said later of that night. So Bryant and Milam just filled him so full of poison that he was hopeless.

Finally, the two men shot Till in the head, neck-anchored him with barbed wire to a seventy-five-pound gin fan, then scuttled his corpse in the nearby Tallahatchie river.

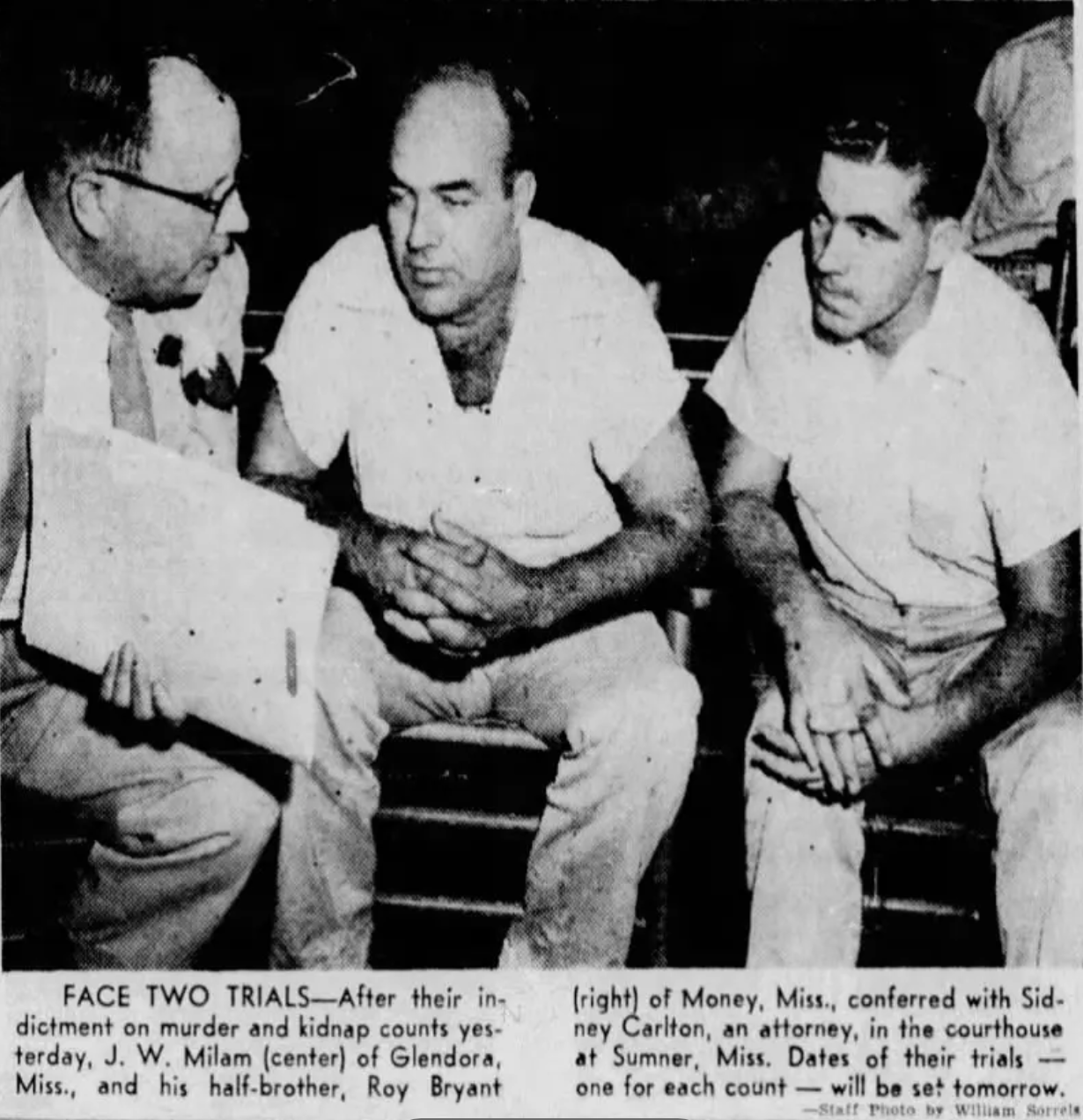

Both men quickly found themselves on trial in Sumner, Mississippi where—not at all ironically—the town slogan was “Sumner: a good place to raise a boy.”

Mamie Till—Emmett’s mother—placed his bloated and mangled body on display for five days. Its sight sent the nation into a rage. Coast to coast, communities scorched the Sumner enclave for being deeply white, deeply southern, and deeply racist.

But it was that same community that would hear the Till case.

And, it was that same community that would eventually find both Till’s murderers not guilty.

No one has ever been convicted of what can arguably be called one of the most open, notorious, and unambiguous episodes of human depravity in our nation’s story. That returns us here. On the one hand, we finally have Carolyn Bryant’s death. But on the other, we have no murder convictions.

Can America surrender even a little of her rage, giving our backs to the hate maven slipping below our swell?

Maybe.

In the absence of justice and to surrender this rage, sometimes a solid pitch and frequency of karma can help one find solace. The question here is, does such karma exist in America?

Emmett Till’s murder has commonly known facts. But for these questions, we must consider the lesser known narratives.

Notably, Wikipedia has dedicated none of its intellectual capital to media pages about the Till killers. Outstanding! Those wanting to know more of them can record-troll as I did.

I reject state censorship with my chest. Still, Wikipedia is a private agent, I am a donor, and that these fleshy puss sacks receive not even a benign benefit give my heart little optimism bursts.

May these vile creatures fade in ignominious anonymity, their loss make room for our moral conscious to mend, and the liberation spark profound national growth.

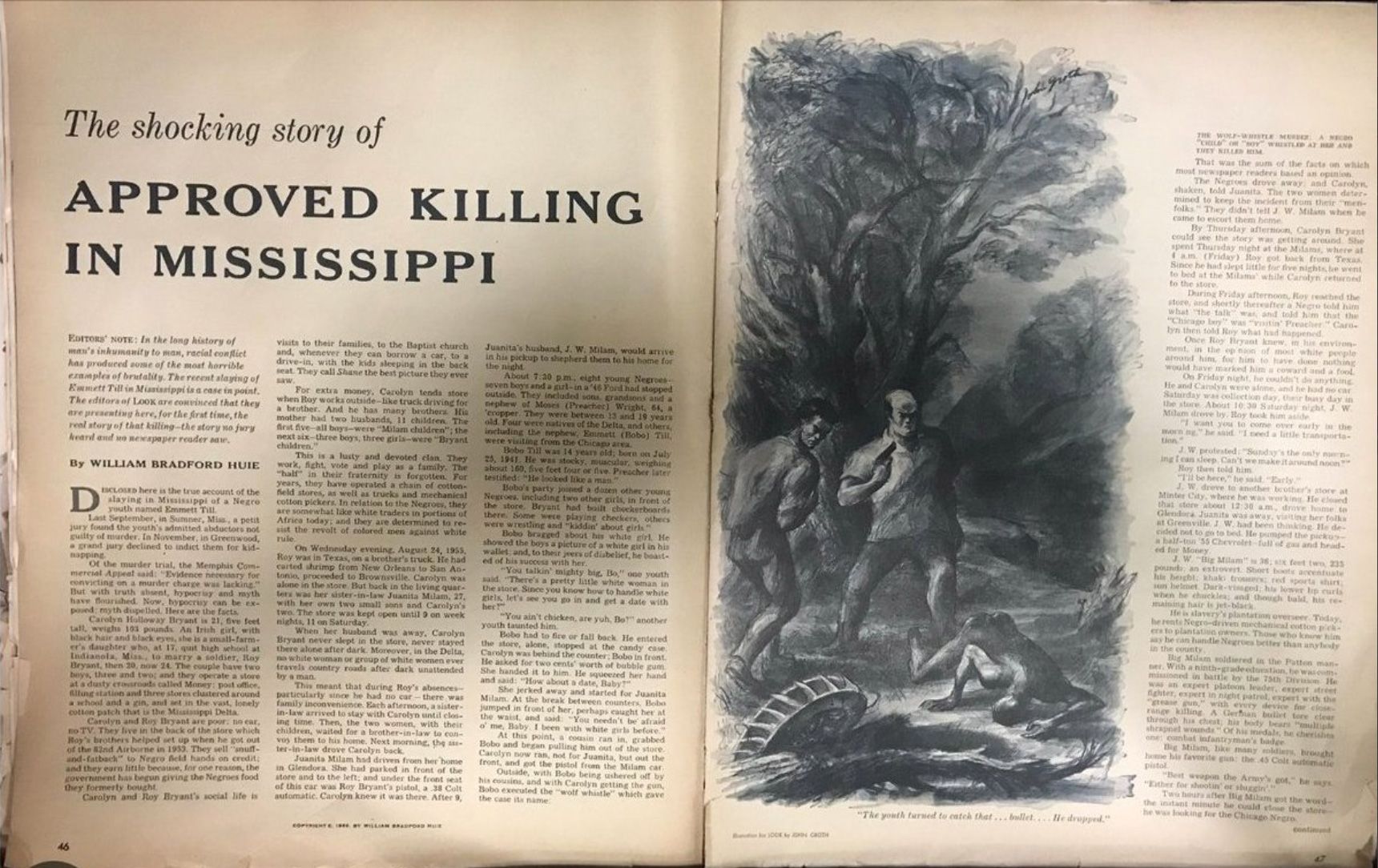

Less than a month after their trial, Look magazine paid Bryant and Milan $4,000 for their murder stories, published in its January 1956 edition. In “The Shocking Story of Approved Killing in Mississippi,” the men explained in graphic detail how they kidnapped, beat, and killed Emmett Till, before dumping his body. Why? Because local Black residents had already forced the families into unsustainable poverty since Till’s death.

Despite reopening the family business immediately after their verdicts, Bryant and Milan could not even make $100 after as long as three weeks. That is because Black residents refused to frequent their store, choking off almost all of their income.

The local white community also financially starved Milan and Bryant, almost before the end of their trial. Friends who had contributed to their defense funds financially cut off both men. Banks also refused to grant loans to the Bryants to seed and manage key crops.

Both men expected their tell-all to improve their existence. It did not. It expedited their disassembling.

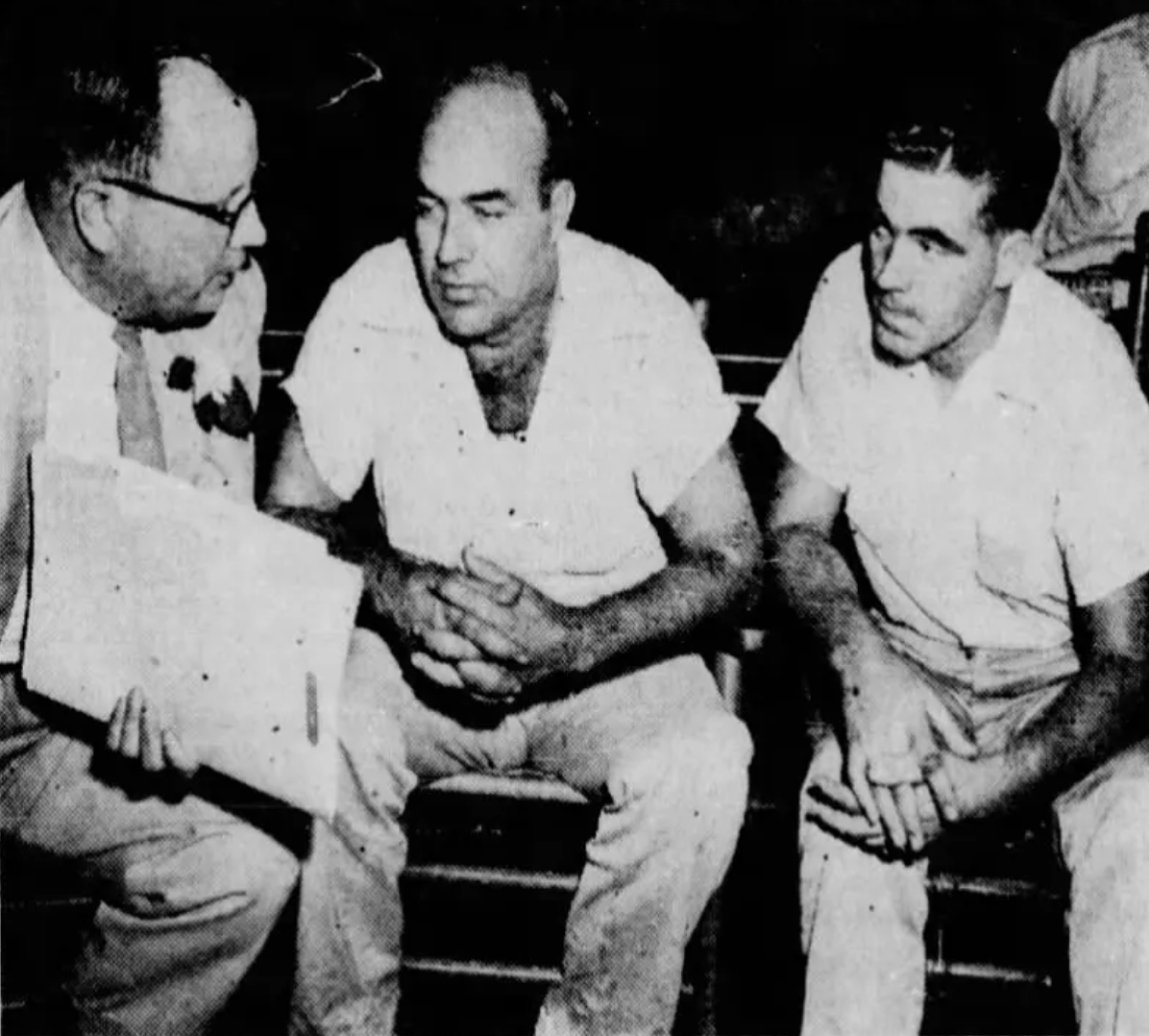

Look interviewed Milam and Bryant again in 1957. Though they smiled for photos, Look said both men clearly suffered from “disillusionment, ingratitude, resentment, misfortune.”

Despite no outward collusion, the combined rejection of the families by the Black and white communities delivered Bryant and Milam their ousters. They forced the families into bankruptcy, into shuttering their businesses, and ultimately out of the state.

J. W. Milam

After Till, the Milam family received little pity. J. W. owned no land. He had no support among his former backers. No one would rent to him. It took a year for the Milam family to find a new farm and for J. W. to secure a loan. He did so only after getting help from one of his former defense attorneys—John Whitten—who sat on a loan committee.

That was not enough to save the Milam family. Local Black labor still refused to work for J. W. He had to then turn to white laborers, who did the same work, but for higher pay.

J. W. Milam was . . . acquitted in the trial, but he was not acquitted by the people of this area. —Mike Studivant, Landowner, Glendora, Mississippi

Milam’s bottom eventually fell out. Quite deliciously, Milam finally was reduced to working for three years effectively as an enslaved laborer doing menial jobs on local plantations. He eventually got heavy equipment work but that, too, was short-lived.

Milam remained intimately connected to the court, going from conviction to conviction for writing bad checks, committing assault and battery, and using stolen credit cards.

Milam never recovered from his Till haunting. When doctors diagnosed Milam with spinal cancer, he was forced into early retirement. Spine cancer is a rare, aggressive, painful, and severely debilitating disease, and it lived up to all of that for Milam. He suffered that way until he finally fell to his disease at the close of 1981.

On December 31, to be precise.

Because God did not want J. W. Milam to sully even a second of the new and beautiful year.

Carolyn and Roy Bryant

After the collapse of the family business and their shunning by Tallahatchie County, the Bryants moved to Texas. Once there, the family could barely survive on Roy’s odd jobs, where he cleared a scant seventy-five cents a day. Roy would later commit—then get caught at—welfare fraud to survive.

Emmett Till haunted the Bryant family even in Texas. Roy tells the story of a time he saw a fellow former Mississippi resident, having recognized his Tallahatchie County license plates. Roy waved and called out. On hearing Roy’s name, the person drove away without so much as speaking to him.

Roy lived in increasing hermitage and fear. Despite publicly confessing his murder in gruesome detail, Roy suddenly began denying he even knew of the Till slaying. His voice would become a growl at the mention of Emmett Till’s name. “He’s been dead 30 years and I can’t see why it can’t stay dead,” he would say.

Claiming he was afraid of physical violence, Roy took pains to live obscurely. “This new generation is different and I don’t want to worry about a bullet some dark night,” he said.

But not ironically.

In Texas, Roy worked as a boilermaker, which he claims cost him his vision. Roy slowly lost his sight until he finally crossed over into legal blindness.

Carolyn and Roy Bryant had four children. Three of those children were ill, impaired, and/or died. One son died of complications from cystic fibrosis. Another died of heart failure. Their youngest child—a girl—was born deaf.

Carolyn remained America’s consummate Karen prototype. She quite literally — and again without the slightest of irony — saw herself as among the Till victims.

Roy and Carolyn eventually divorced.

Roy Bryant died in September of 1994. Like Milam, Bryant died of cancer. Not for any particular reason, Roy Bryant Sr.’s remains are interred at the Lehrton Cemetery in Ruleville, Sunflower County, Mississippi, USA, coordinates: 33.72500, -90.58170.

Following Till’s murder, Carolyn suggested she never felt anything but harassed. In that vein, and last year, the New Black Panther Party kindly visited Carolyn at her North Carolina and Kentucky addresses. They were there to serve unofficial “warrants” for her arrest and trial.

Carolyn remained America’s consummate Karen prototype. She quite literally — and again without the slightest of irony — saw herself as among the Till victims. In fact, Carolyn wrote a memoir to tell her “side” of the Emmett Till story. The idea was for Roy and Carolyn’s daughter to publish Carolyn’s ninety-nine-page memoir—“I Am More than a Wolf Whistle: The Story of Carolyn Bryant Donham”—in 2036, posthumously.

Historian Timothy Tyson leaked it to the public in 2022 instead. In this way, he positioned Carolyn to be a firsthand witness to its overwhelming scorn and derision.

Carolyn Bryant died in hospice care on Thursday, April 27, after finally succumbing to her battle with — won’t he do it? — cancer.

Catherine Pugh is an Attorney at Law and former Adjunct Professor at the Temple University, Japan. She developed and taught Race and the Law for its undergraduate program, and Evidence, Criminal Law, and Criminal and Civil Procedure for its law program. She has worked for the Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division, Special Litigation Section, and was a Public Defender for the State of Maryland. View her Race and Profiling Lecture Series appearance here. The view expressed here are personal. Nothing in this or any OHF Weekly writing is a legal recommendation, legal advice, or a legal opinion.