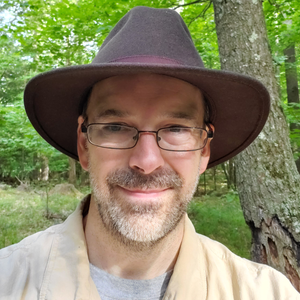

I remember having a conversation a decade or so ago with a teacher at a private school near the liberal hotbed of Northampton, Massachusetts. He told me that all the white teachers at his school supported affirmative action, until their kids applied to college. His comment reflected a society-wide trend. We support justice in the abstract, but not if it hinders our family’s odds of getting into the right college or being hired for the perfect job. That has now changed with Justice Roberts and his six-justice majority striking down affirmative action in Students for Fair Admissions, Inc, v. The Trustees and Fellows of Harvard University. Claiming that Harvard and the University of North Carolina’s affirmative action programs violated the equal protection clause of the fourteenth amendment. Colleges may still “consider an applicant’s account of how race impacted his or her life. . . .” [1]

Affirmative action as federal policy had its roots in the 1960s. Lyndon Johnson issued Executive Order №11246 which required contractors to “take affirmative action to ensure that applicants are employed, or that employees are treated during employment, without regard to the race, color, sex, or national origin.” The Johnson administration expanded the list in 1967 to include “sex.” The following year the Department of Labor required contractors to establish “goals and timetables for the prompt achievement of full and equal employment opportunities. Targeted groups included Black, Asian, American Indians, and Hispanics. While Johnson had not established “quotas,” the government was clearly strengthening policies which aimed to undo the legacies of discrimination in the workforce. [2]

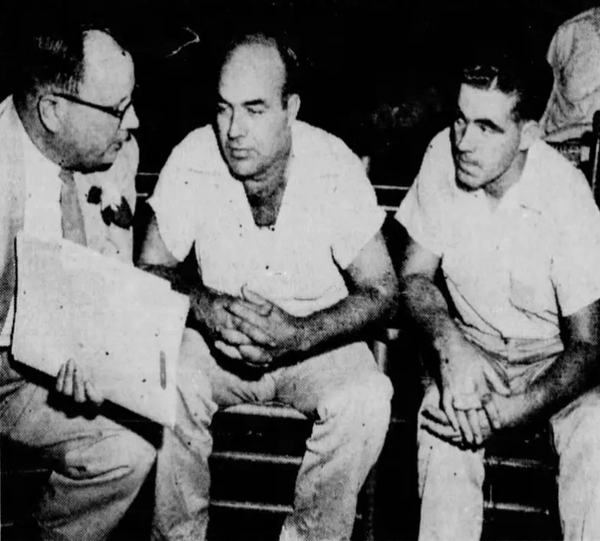

George Shultz, who served as Secretary of Labor for the Nixon administration, further strengthened affirmative action. He proposed, with Nixon’s support, the Philadelphia Plan, which required government contractors to establish “goals and timetables” to hire Black apprentices for their businesses. By 1970 the Nixon administration applied this policy to all hiring and contracting by the federal government. No longer would civil rights laws in employment to be based on merit alone and color blind, now they would consider past discrimination in American life and establish quotas to remedy past wrongs. Almost immediately, corporations, universities, and unions were put on notice that they needed to change their practice. [3]

Historians primarily remember Nixon’s civil rights policies based on his Southern Strategy, which sought to enlist the support and votes of white Southerners who had previously been Democratic but resented the parties aggressive support for Civil Rights. Nevertheless, Nixon strongly supported the Black community on affirmative action and judicial nominees. Nixon appointee and new Chief Justice Warren Burger wrote the 1971 decision Griggs v. Duke Power Co., which ruled that employment tests with discriminatory effect, but not discriminatory intent violated Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. When Nixon’s efforts to appoint a Southerner to the high court were thwarted, he went on to name Harry Blackmun. Blackmun later wrote the crucial 1978 decision Regents of the University of California v.Bakke. In his conclusion Blackmun asserted, “In order to get beyond racism, we must first take account of race.” [4]

Blackmun’s quotation asserted that affirmative action policies were meant to be temporary until we had gotten past racism. How long would affirmative action policies need to remain in place? Sandra Day O’Connor famously wrote in her 2003 concurring opinion in Gratz v. Bollinger that affirmative action programs would no longer be necessary in twenty-five years. While the court beat her suggested timetable by five years, we have clearly not gotten past racism. Just three weeks ago the Court struck down a voting map in Alabama for diluting the Black vote and ordering a new map be created in which at least two districts would have a majority of Black voters. Any glance at the headlines over the past fifteen or more years reveals the myriad of ways that America is still mired in racism.

But if race-based affirmative action has been blocked by the high court maybe a new approach is needed. David Brooks recently editorialized in the New York Times about the need to move to affirmative action based on class.

As class happens to be a pretty good proxy for race in the United States, such class-conscious policies would continue to benefit racial minorities. Furthermore, by giving a leg up to poorer whites, it would expand economic and experiential perspectives on college campuses.

I had several students complete projects on the continuing debates about affirmative action in American life. My Chinese American students were very interested in the outcome of the case, especially since they will be applying to college this fall and do not want to have their race used against them in admission decisions. While they celebrate that an obstacle to their achievement has been removed, I am certain that the decision bodes poorly for the admission of Black and Hispanic students.

When California voters rejected affirmative action in admission decisions to their state colleges and universities. As Zachary Bleemer explained during a recent interview for NPR’s Morning Edition, “Berkeley and UCLA, the most selective public universities in the state, saw a declines in Black and Hispanic enrollment of about 40% immediately the year after the Proposition was implemented.” He later explained the longer-term impact of the change,

[Blacks, Hispanics, and Native Americans were] less likely to earn graduate degrees. Among lower-testing students, they’re less likely to ever earn an undergraduate degree at all. They’re less likely to earn degrees in lucrative STEM fields. And if you follow them into the labor market, for the subsequent 15 or 20 years, they’re earning about 5% lower wages than they would have earned if they’d had access to more selective universities under affirmative action.

We will all have to act to be sure that the United States does not see a similar decline. Continuing to support and fund high quality public education across the country is essential. The work of community groups, private charity, and individual volunteers will also be important. We must not allow the educational gap between all ethnic groups to grow. Otherwise, our economic divisions, social, and cultural divisions will only widen.

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/06/29/us/affirmative-action-decision-document-supreme-court.html

[2] Quotations and additional information from James T. Patterson, Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945–1974 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 642.

[3] Patterson, 723.

[4] Penda Hair, “Eloquent voice for the oppressed: Harry A. Blackmun 1908–1999” Harvard Law Bulletin Summer (1999) Accessed at < https://hls.harvard.edu/today/eloquent-voice-for-the-oppressed/> June 29, 2023.