There was a time when bipartisanship was the rule on Capitol Hill. Famously, Democratic Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill protected his drinking buddy, Republican Silvio Conte, from redistricting efforts that would turn Massachusetts’s sole Republican district into a Democratic, or at least a competitive, one. To O’Neill, whose autobiography was titled Man of the House, relationships were more important than partisan affiliation.

Since O’Neill and Conte’s deaths, by the way, that district has become solidly Democratic. No longer was O’Neill there to protect his buddy’s political base.

President Lyndon Johnson, a Democrat who was revered for his legislative deal-making ability, relied upon Republicans to help him pass his signature legislation: the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Indeed, a higher percentage of Republicans voted for the bill than Democrats, and in the House, a Republican Congressman representing a conservative Ohio district, William McCulloch, took the lead. It’s ironic indeed that civil rights has become the issue Republicans have since used to wrestle power from the Democrats, a shift Johnson predicted when he lamented that the Democratic Party may “have lost the South for a generation.”

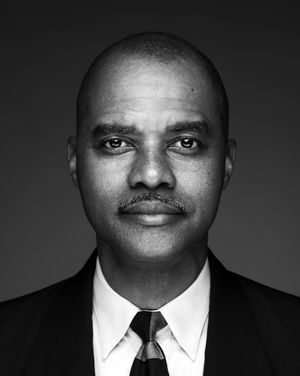

As a young legislative staffer on Capitol Hill in the early 1990s, I often griped to my friends about the gutless Democrats who were far too cozy with Republicans. I was particularly outraged as I watched many Democrats turn their backs on the testimony of Anita Hill and vote in favor of Clarence Thomas’ nomination to the Supreme Court. Eleven Democratic senators supported the nomination, which only passed by a fifty-two to forty-eight margin. Although then Senate Judiciary Committee chairman Joe Biden ultimately voted against the nomination, his aggressive stonewalling of witnesses backing Hill’s accusations gave political cover to those Democrats who wanted to vote yes. Had Biden allowed a more thorough vetting of Hill’s accusations, Thomas’ nomination would have been further sullied, likely embarrassing Democrats and Republicans who were committed to supporting him. Apparently, Biden did not want to embarrass these colleagues from both sides of the aisle.

. . . bipartisanship is not a cause in and of itself. Bipartisanship is an outcome resulting from issues achieving broad support among decision makers.

Biden has stated that he missed those days, acknowledging that he could work with “old fashioned Democratic segregationists.” “You’d get up and you’d argue like the devil with them,” Biden recalled, “then you’d go down and have lunch or dinner together.” Biden’s evocation of that period made many progressives, like myself, nervous about his candidacy.

Much to our surprise—and gratification—Biden appears to have jettisoned his longing for bipartisanship, instead aiming to accomplish big things. But whenever Democrats push to achieve important legislation that the Republicans often oppose, the handwringing over the loss of bipartisanship reappears in the comments of Republican leaders.

To be sure, such arguments for bipartisanship are very convenient. Republicans ignored process as well as budget implications when they pushed through their tax giveaway to the rich. Nevertheless, despite the obvious hypocrisy of those arguments, some in the media repeat them as if they are legitimate political discourse.

Certainly Congress was a more pleasant place to work when there was greater comity among members, and the rancor between the political parties was mitigated. But bipartisanship is not a cause in and of itself. Bipartisanship is an outcome resulting from issues achieving broad support among decision makers.

A recent—and rare—example of bipartisanship would be the original coronavirus relief bill passed in March 2020. Passing the House with a nearly unanimous voice vote, the bill was widely supported due to the crisis that the pandemic represented. For once, as Democratic Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi pointed out, legislators negotiated in good faith, and “Many of the provisions in there have been greatly improved because of negotiation.” Such crises pushing legislators to work cooperatively, however, are few and far between these days.

On a longer-term basis, how could Congress achieve widespread agreement on policy despite America’s diversity? By excluding voices that disagree with the consensus. When there was bipartisanship, the internet did not exist, and cable was in its infancy. As a result, it was expensive to communicate to large numbers of people, and the media was truly a mass media, with the discourse in each metro area controlled by just a couple of newspapers and a few broadcast television stations. The Equal Time rule under which the Federal Communications Commission mandated that radio stations grant opposing views equal time for debate still existed, ensuring that alternative voices, those located outside the mainstream both on the right and the left, were disregarded. Almost everyone worked from the same basic sources of information.

Now, with the internet, cable and the elimination of the Equal Time rule, media has become splintered. No longer do Americans of all stripes listen to the nightly news delivered by Walter Cronkite or Dan Rather. No longer do we all read the same newspapers dropped on our front porches every morning. Those news sources were read by broad swaths of Americans, resulting both in all Americans having a common understanding of the facts, and in the news sources being scrubbed of anything really controversial. In contrast, now media thrives by targeting a narrow ideological niche and exploiting it. While this change allows previously silent (or silenced) voices to be heard, such as LGBTQIA or Black Lives Matter, it also results in a lack of agreement over basic facts, as we sort ourselves into MSNBC or Fox News viewers.

In addition to broad agreement on the issues, stakes were low pre-internet. In the post-World War II period, and especially since the election of Jimmy Carter in the 1970s, America has had a dominant ideology. Sometimes called “neo-liberalism,” that ideology had classical economics as its doctrine, idealizing open markets, free trade, limited taxes and deficits, and placed America, particularly white, straight male America, on a pedestal.

Fundamentally, America is changing from a majority white patriarchal society to a majority minority society.

During this time, Congress was made up almost exclusively of straight white men, as was the leadership in the media and in business. As a result, the issues that were debated were those that came to the attention of a relatively narrow, monolithic group. Since this group generally shared the same perspective, and since they were the establishment, issues that would change the system were not even considered.

That all changed with the election of Barack Obama. Even though ideologically he fit very well with those who came before him, he violated a basic tenet of the prior social contract: he was Black. This shock to the system opened the door to overt racism and the election of Donald Trump who completely abandoned the prior orthodoxy.

More important than the ability of alternative voices to publicize their views now is the nature of the change we are undergoing. Fundamentally, America is changing from a majority white patriarchal society to a majority minority society. This demographic change is what is driving all the political and social disruption we are experiencing, whether it be experienced as the increasingly virulent racism we see displayed in citizen-recorded videos, the election of Donald Trump, or the passionate antagonism the two parties direct at each other.

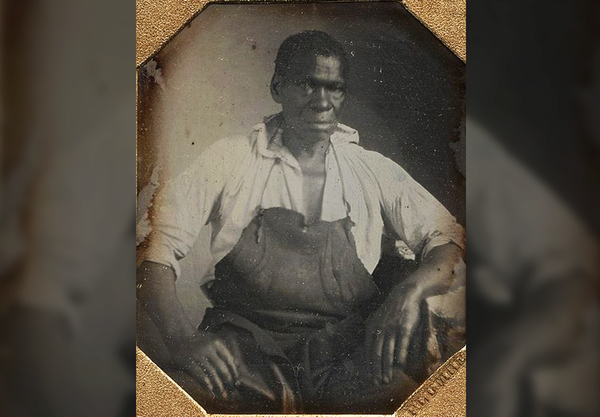

We cannot underestimate the foundational nature of this change. Reconstruction in the wake of the Civil War failed to end the institutional racism of slavery largely because of the fact that the United States was still entirely ruled by white males. The visionaries behind Reconstruction, led by former General and Republican President Ulysses S. Grant, envisioned it as a movement to redefine the role of Black people in American society. Southern resistance to that effort proved more unyielding than expected, and after awhile, the American electorate of the era, dominated as it was by white men, tired of the effort and pushed political leaders to end it prematurely. One wonders if women, people of color, and other marginalized groups had made up the majority then whether America’s leaders would have been so quick to abandon that policy.

But now, as Yoni Appelbaum stated in The Atlantic, “The United States is undergoing a transition perhaps no rich and stable democracy has ever experienced: its historically dominant group is on its way to becoming a political minority—and its minority groups are asserting their co-equal rights and interests.”

The last time America wrestled with such fundamental issues, our nation ended up nearly destroying itself through civil war. During the period preceding that conflict, bipartisanship was non-existent in Congress. Indeed, relations between the parties are downright chummy now compared to then. After all, we haven’t seen the kind of violence in Congress that we saw in 1856 when pro-slavery Democrat Preston Brooks beat nearly to death abolitionist Republican Charles Sumner on the Senate floor. That said, the attack on the Capitol building on January 6 was without precedent.

Any call for a return to the days of bipartisanship, therefore, is a call for us to return to the days when a small group of white men decided everything, and the voices of anybody different could be ignored. Truthfully, the white men would have continued their dominance if not for the fact that demographic change is making it impossible for them in a democratic republic. In effect, until recently, the marginalization of people who were not white males was simply assumed. Until we can complete the transition from a society defined by its white patriarchy to a diverse society in which people of different backgrounds wield real political power, any calls for bipartisanship are veiled calls for a return to that constrained past.

Member discussion