Over this past year, there has been an uptick in hate crimes perpetrated against the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community. Unfortunately, many of these attacks have come at the hands of African Americans. This has prompted many in the media and online platforms to push the narrative that there are heated tensions between the Asian and African American communities. And some imply that all xenophobic incidents are originating solely from the Black community. This narrative is an age-old tactic of white supremacy to keep these communities at odds with each other.

While there are elements of anti-Black sentiment among older generations in the Asian community, others are working toward allyship. History shows that these two groups have not only existed peacefully with each other but have in fact thrived by joining forces to fight the oppression they both faced under white supremacy.

How It All Began

The narrative of tension between the two communities began after World War II. The rise in African Americans asserting their claims for the same rights as their white counterparts led to the Asian and other communities of color banding together in support. As a method of pushback, the media began asserting the narrative of the model minority. Its purpose was twofold: first to create a wedge between the two communities, and second to cast doubt on the fact that racism had impacted Black progress.

According to Harvard’s online publication The Practice, “the term model minority has often been used to refer to a minority group perceived as particularly successful, especially in a manner that contrasts with other minority groups.” The classification gave Asians and Asian Americans a certain level of privilege and access under the white supremacy framework, as well as a reason to distance themselves from African Americans who were stereotyped as lazy and criminal. Suddenly, everyone was making comparisons between Asians and African Americans.

As it is with many older people in the AAPI community, many African Americans only have interactions with people of Asian descent when they are patronizing their businesses.

The most popular at the time was a story by sociologist William Petersen in 1966 titled “Success Story, Japanese-American Style.” His highly influential piece implied that while Japanese Americans had been placed in internment camps and faced other forms of discrimination, they could still overcome those obstacles and rise to success by being industrious and law-abiding citizens.

Describing African Americans, he says that when faced with opportunities to succeed, “the minority’s reaction to them is likely to be negative—either self-defeating apathy or a hatred so all-consuming as to be self-destructive.”

Still today many in the AAPI community have internalized the model minority myth and believe that if only Black people worked harder or obeyed the law, they wouldn’t be so far behind. However, scholars have argued that it was not merely hard work that allowed some Asians to thrive, and discrimination was not as prevalent as it is for African Americans and opportunities were more plentiful for them. Nathaniel Hilgers, an economist at Brown University, wanted to get to the truth of why some Asians were closing the racial wealth gap between them and white individuals. So he analyzed past census records to track the incomes of Black, white, and American-born Asian people during the early to mid-20th century.

The level of education gained by Asian Americans had no tremendous impact on their ability to close the income gap with white workers. Hilger’s research suggests that “society simply became less racist towards Asians.” He found that contrary to the idea that Asians came here poor and unskilled and could then pull themselves up by the bootstraps to become successful, by 1965, “changing laws ushered in a surge of high-skilled, high-earning Asian workers, who now account for most of the Asians living in the United States today.”

Another interesting tidbit is that Asians with the same amount of education as their white workers were paid less than their white counterparts in 1940, but by 1980 the pay rates were almost the same. Hilger says, “Asians used to be paid like Blacks. But between 1940 and 1970, they started to get paid like Whites.” They did not give African Americans that luxury, even though they had the same education as both Asian and white Americans, and worked just as hard. Hilger’s research shows that “the greatest thing that ever happened to them [Asian Americans] wasn’t that they studied hard, or that they benefited from tiger moms or Confucian values. It’s that other Americans started treating them with a little more respect.” People seem to thrive when we remove the shackles of white supremacy.

This internalization of the model minority myth, combined with the fact that many older Asian people who have had limited or no interactions with individuals from the Black community are forming their opinions based on their own biases and the media images that they consume, much like many white people, leads to the way AAPI react to Black people. We see this in the way they interact with African Americans when they open up businesses in our communities. A chief complaint of African Americans with the AAPI community is the disrespect and blatant disregard for the communities they are setting up shop in.

. . . we still see the media actively seeking to create or emphasize tensions between the AAPI and African American communities.

As it is with many older people in the AAPI community, many African Americans only have interactions with people of Asian descent when they are patronizing their businesses. Often, these experiences are not positive. I have visited several beauty supply stores in various cities in various neighborhoods, and in the vast majority of those instances, they followed me around the store as if they were certain I was only in there to rob them blind. These store owners were often rude, and out of all my experiences, I have rarely seen an African American employed by the businesses. I found one who worked as a security guard. Once I became a hijab wearer, my experiences changed. I can only surmise this is because I am often perceived as something other than African American.

Experiences like mine are not unique. Members of the AAPI community come into African American communities to set up their business and do not give back to the communities that have received them and are spending their money in their shops. Nor do they hire African American workers from the communities they are in. These issues create resentment that can have catastrophic effects when efforts to overcome them are lacking.

Same Story, Different Day

In addition to those biases, we still see the media actively seeking to create or emphasize tensions between the AAPI and African American communities. The AAPI community has been subject to an increase in racially motivated assaults, and African American individuals have perpetrated many of these incidents. But these individuals’ actions are not representative of the Black community.

Even though a white male targeted and murdered six Asian women (of eight victims), the media and online platforms are not pushing the narrative that there is tension between the AAPI and white communities. Even though white individuals perpetrated many of the almost 3,000 incidents to which the AAPI community has been subjected. Why is that? Why is footage from that horrible incident not included in the loop of assault footage that we see come across our screens daily?

It seems there is a conscious effort to prevent any attempts at allyship between these two communities that are both impacted by white supremacy. There are groups within both the Black and AAPI communities out there advocating for unity and doing the work necessary to foster unity, but these actions do not receive nearly as much coverage in the media.

Overcoming the Narrative

All we have to do when seeking solutions to the issues these two communities face is look to our shared history. Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, notable Black people used their influence to speak against racism and racial violence directed toward the AAPI community.

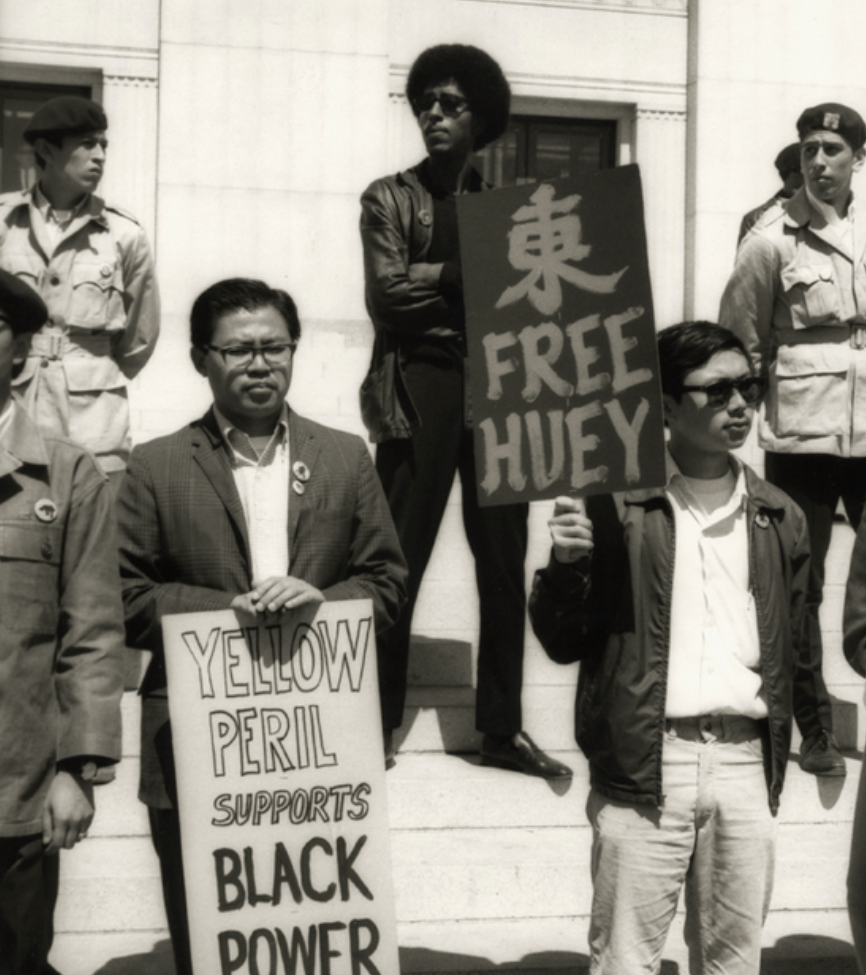

In 1869, Frederick Douglass spoke out against America’s attempts to severely limit Chinese immigrants’ ability to enter the country. Throughout the twentieth century, Black activists aligned themselves with their AAPI brothers and sisters to demand basic human rights for all people. They spoke out against acts of racial violence perpetrated against Asians and were not in favor of going to war against the Vietnamese. In 1982, after the murder of Asian American Vincent Chin, Jesse Jackson and other Black activists took part in the movement to get justice for his family.

W. E. B. Du Bois also believed that the AAPI and Black communities should be allies, speaking out against prejudice suffered by Asians at the hands of white supremacy. On the flip side, there were members of the AAPI community actively fighting against anti-Black racism alongside their Black brothers and sisters. H.G. Mudgal, the Indian immigrant editor of Marcus Garvey’s newspaper The Negro World and fixture in Harlem’s political scene, advocated for Marcus Garvey’s views on helping African Americans fight white supremacy. Yuri Kochiyama was another AAPI ally who fought alongside Black activists like Malcolm X, who inspired her to join the cause. Minority students at the University of California at Berkeley formed the Third World Liberation Front, comprised of Asian, Black, Native American, and Hispanic groups to push for ethnic studies at the university.

Asian people need to explore their history to understand how some of those anti-Black sentiments came to be and try to understand and appreciate the shared experiences of racism both communities have faced to shed the biases they carry. And Black people need to do the same, recognizing that together we are stronger and we need to unite to dismantle the system of white supremacy. Even though we don’t see it as often as we do the visuals of the Black and AAPI communities at odds, there are activists and regular people in both communities having the necessary conversations and taking actions to dispel the hurtful narratives, replacing them with one that reflects the unity our communities once shared, and continue to work toward shared goals.

. . . twenty-five years ago, we learned a lesson in what the lack of political power and cultural misunderstandings between minority groups can do, it can destroy us.

Proof that out of tragedy can come understanding, allyship occurred after the 1992 Los Angeles riots. During the riots, African Americans burned stores in the Korean area of LA over anger at the acquittal of the four officers who pulverized Rodney King and the murder of Latasha Harlins, a fifteen-year-old killed by Korean liquor store owner Soon Ja Du. Du served no time for the crime, and that, along with the Black community’s resentment over the Korea business owners’ disrespect toward their community, was the breaking point. But the aftermath forced the Korean community to look at their anti-Black sentiments and work towards understanding it and work toward building unity with the African American community.

Chang Lee, a Korean American who defended his store during the riots, came to realize that “twenty-five years ago, we learned a lesson in what the lack of political power and cultural misunderstandings between minority groups can do, it can destroy us.”

The Korean American Council, a nonprofit, formed the Alternative Dispute Resolution Center to bring the two communities together after the riots. Andy Yoo, who was the son of one of the store owners, believes that “we, the Black and Korean communities, were pitted against each other without understanding each other. We have to engage each other. I learned that the powers that be will try to divide and conquer.” We can change biases as long as we are all willing to get to know each other and respect each other. African American and AAPI unity can then be the prevailing narrative.

For more information on supporting the Asian American Pacific Islander community or to report an incident visit: https://stopaapihate.org.