The debate is raging about whether or not enslaved people accrued some benefit from having learned skills during slavery. There’s little question that Black people did all kinds of work while enslaved. They were mechanics, carpenters, blacksmiths, domestic workers, and tailors, as well as doing agricultural work. The State of Florida points this out to us in their State Academic Standards, suggesting some benefitted from the training they received as slaves. It should be pointed out that African enslaved people brought some of their own expertise to America, especially in agriculture, music, and art.

SS.68.AA.2.3 Examine the various duties and trades performed by slaves (e.g., agricultural work, painting, carpentry, tailoring, domestic service, blacksmithing, transportation). Benchmark Clarifications:

Clarification 1: Instruction includes how slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.

Depending on where they were, formerly enslaved people could indeed utilize those skills, but it rarely worked out well for even the most skilled among them. Freedom came to one group of enslaved people in the nation’s capitol via the DC Compensated Emancipation Act of 1862. Three thousand one hundred slaves were freed and released, among them a mix of all the skills listed above. Their white owners were given reparations, and some freed people took the compensation offered if they agreed to be exported to Liberia. President Abraham Lincoln hoped to export almost all formerly enslaved people, but Frederick Douglass and others convinced him otherwise — only after he tried it and failed, however, on Cow Island off the coast of Haiti.

Almost thirty years earlier, in 1835, free entrepreneur Beverly Snow owned an Epicurean Eating House that had gotten too successful. Anti-abolition forces looted his restaurant and destroyed other Black businesses during the Snow Riot (it wasn’t a riot). Washington, DC, had been experiencing labor issues, including the 1835 Washington Navy Yard labor strike. In addition to discontent with hours worked and limited lunch privileges, white caulkers were upset about free Black caulkers, who they felt were taking jobs they were entitled to. There was a rumor that Snow made a comment about a white mechanic’s wife; the mechanics destroyed Snow’s restaurant, drinking all the liquor while they were there. Mobs of white men attacked the remaining Black-owned businesses, churches, and schools. Snow and other Black businessmen were forced to flee. Being a free skilled Black person was no advantage in Washington, DC.

Then came the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. The Proclamation didn’t exactly free Black people. It said that anyone who escaped from the Confederacy and made their way to free territory would be free unless Union troops had already arrived where they were. Many enslaved people made their way to freedom; a high percentage of them headed for Washington, DC, which had nowhere to put them.

DC set up contraband (refugee) camps where freed enslaved people, skilled or not, were literally starving, with many succumbing to disease in unsanitary conditions. Formerly enslaved people not otherwise employed were put to work on abandoned farms, including Robert E. Lee’s estate, to raise money for the Union.

A portion of the contrabands at present at the Contraband Camp in Washington are to be immediately employed in cultivating General Robert E. Lee’s estate, at Arlington, and other abandoned farms in the vicinity, in Virginia, for the purpose of raising forage. All of the contrabands who are able to work and not otherwise employed will be at once put to work for this purpose. —The Alexandria Gazette

The Union had, in effect, returned free people to slave labor, having nothing else to do with them. This would be a precursor to what would happen at the war’s end.

Within eight months, between April and December of 1865, America experienced the end of the Civil War, Juneteenth, and the passage of the 13th Amendment, effectively freeing almost all enslaved people in America. All four million of them. They generally didn’t own land, had little or no money, and nowhere to go. In General Order 3, read to the enslaved people in Galveston, Texas, on Juneteenth, Union Major General Gordon Granger told the formerly enslaved:

The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.

In other words, “You’re free but don’t expect any help from the U.S. Government. Go back to your plantations and hope your former owners will now pay you for the same work.” There were no special provisions or benefits for skilled workers. Ron DeSantis was formerly a history teacher and might be expected to know that. Ask DeSantis how many Black businesses there are with signs in their window, “Established in 1865.”

Those four million formerly enslaved people wandered away from their former circumstances; many ended up wandering back. Some were forced back by the new Black Codes, enacted in the Southern States that had seceded from the nation. Among the provisions included were that Black people had to have work contracts or be forced to return to their plantations. They couldn’t enter into professions without approval from white officials. Black people couldn’t marry, vote, serve on juries, or travel freely. Skilled Black workers had few options that didn’t involve working for their old masters, other than heading West or North or forming their own communities.

The Black Codes are mentioned three times in Florida’s guidelines, so we know Florida is aware of them. For the first two years after the Civil War, those codes did everything they could to reinstitute enslavement. The Republican Congress noticed and, to their credit, instituted measures to protect the newly freed, including leaving federal troops in place to protect Black people and enforcing the Freedmen’s Bureau Acts passed in 1865 and 1866.

The government, on the one hand, provided protection, offered limited jobs, and built schools. Some skilled domestic workers worked as cooks and maids for the Union troops. On the other hand, those same troops assaulted and raped Black women in the same way as they continued to be treated on plantations after the war. Those domestic skills placed Black women directly in the line of fire.

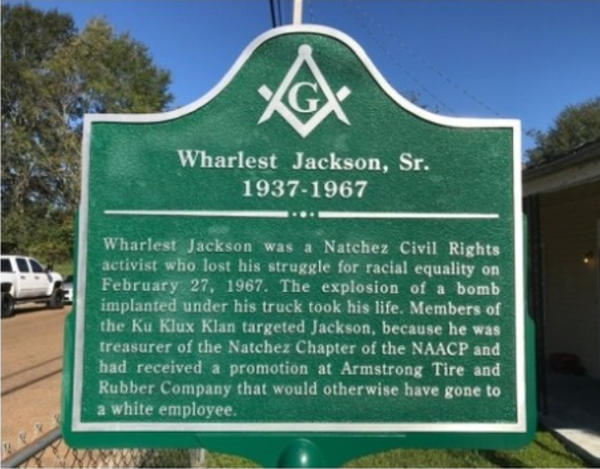

The period immediately after the war also saw the rise of the Ku Klux Klan, which spread violence and terror. Lynchings increased in the South, especially in Florida, which led the nation in per capita lynchings. Do you suppose Florida teaches that? Among those targeted were Black leaders and business owners. Congress beat back the Klan with the KKK Acts of 1870 and 1871. Like the South, they eventually rose again and again.

I don’t intend to leave out Reconstruction. After the passage of the 15th Amendment in 1869 giving Black men the right to vote, what Southerners feared most came to pass, given that in many areas they were vastly outnumbered by Black people. Black people began electing their own to state government and to Congress; in a few cases, they held statewide offices. In Florida, Jonathan Clarkson Gibbs became Secretary of State and Superintendent of Public Instruction of Florida. Gibbs is included in the curriculum in Florida; Gibbs died in office and was rumored to have been poisoned. Do you suppose Florida will teach that part?

Under Reconstruction there was progress; America was on a path to where integration and equality were at least imaginable. But the North got tired of protecting Black people, and with the associated expense, the South relentlessly pursued the return of their way of life in which white men controlled all. A contested Presidential election in 1876 led to the Compromise of 1877, in which Republicans got a President but Southerners won the removal of the federal troops. The following year, the Republican President signed the Posse Comitatus Act, ensuring those troops would never return to protect Black Americans.

After Reconstruction came The Nadir, which is considered the post-slavery low point in race relations. Florida teaches about The Nadir; in some ways, Ron DeSantis is correct when he says Florida’s curriculum is more comprehensive than in many states. Florida covers a lot of ground, never failing to put its own spin on history.

The Florida curriculum browbeats children into accepting how badly America wanted to end slavery from the beginning. It often speaks of the growth in numbers of enslaved people as “natural reproduction” instead of the actual means, which were forced breeding and rape. You can’t teach the true history of slavery without mentioning those terms, but that might make white children feel bad, so Florida omits that part.

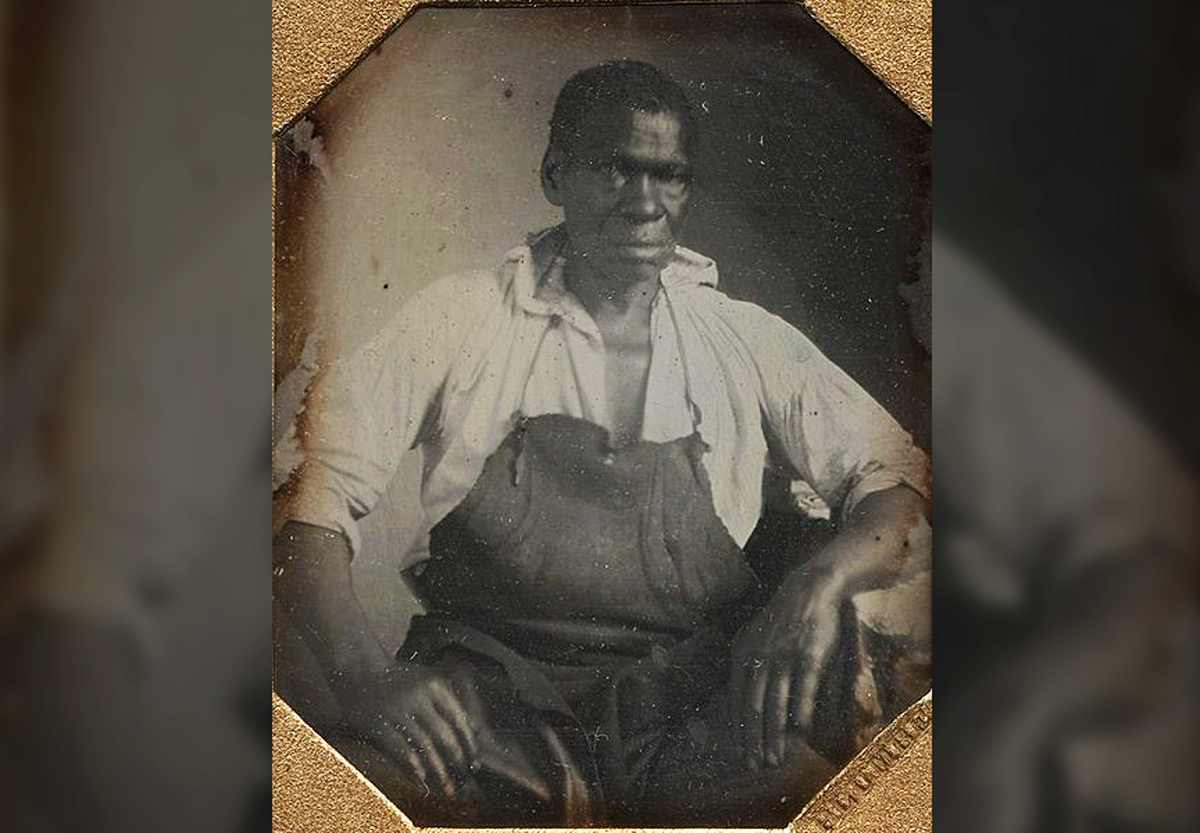

I can think of two cases where skilled enslaved people arguably made a better life for themselves once free. The cover photo is Isaac Granger, who was at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello. His extended family were enslaved there. His mother and father were purchased by Jefferson in 1773. George and Ursula worked as overseer and head cook, respectively. Their three sons, including Isaac, the youngest, were skilled laborers. Isaac spent time working in the nailery at Monticello. Perhaps he avoided the beatings that were given to teen boys in the nailery to increase productivity because he was a good worker. Historian Edwin Betts covered up the beatings he discovered in a letter because he didn’t want to spoil Jefferson’s image.

Isaac went on to become a blacksmith in Monticello’s stables; he was also a tinsmith, another valuable skill. In 1797, Jefferson gave Isaac and his wife and children to his daughter as part of their marriage settlement. Isaac was later leased out to Thomas Randolph Jefferson, who needed a blacksmith, so Granger’s family was moved again. At some point, Granger moved back to Monticello and was there for the last years of Jefferson’s life. At some point, he ran away from Monticello and found work as a blacksmith in Petersburg, Virgina, until age seventy-two. He had little to fear from slave patrols looking for fugitive slaves because he was old. He was unable to visit his family members remaining at Monticello, however, because he had escaped. I’m not sure his skills were of great benefit when measured against the cost.

Nathan Green was born into enslavement in 1820. Green was owned by a firm, Landis & Green, that leased him out to Tennessee preacher and distiller Dan Call. Green didn’t escape to the North after the Emancipation Proclamation, instead staying on as the head distiller for Call. He was introduced to an eight-year-old Jack Daniel and told to take him under his wing.

“I want [Jack] to become the world’s best whiskey distiller — if he wants to be. You help me teach him.” —Dan Call

In 1865, Nathan Green, known as “Uncle Nearest,” gained his freedom after the Civil War ended. The following year, Jack Daniel opened his distillery. Daniel immediately hired “Uncle Nearest” and two of his sons. Eventually, Jack Daniel employed another son and several grandchildren and has employed seven straight generations of Nearest Green’s descendants. Nathan Green created the famous Jack Daniel’s Tennessee Whiskey, yet his name is nowhere to be found in modern company records, and he never owned any stock. Years later, author Fawn Weaver presented documentation to the owners of Jack Daniel’s, who publicly acknowledged his role in 2016. You can make the case that Green was highly skilled, but what did it get him in the end? There is no knowledge of what happened to Green after 1884; his gravesite location is unknown.

I won’t disagree with Florida that many enslaved Black people were skilled. Some were great artisans when they arrived. The presumption that slavery improved their lot is ridiculous on its face; they survived because of their skills and rarely prospered. Even when they did attain success, it was easily and often taken away.

The Greenwood District of Tulsa (Black Wall Street) had many Black businesses and skilled workers, yet the community was burned out and bombed from the air after a false claim of assault of a white woman in an elevator. The Black residents of Ocoee, Florida, were burned out, those who weren’t killed, after two men tried to vote. The residents of the Black community of Rosewood, Florida, were shot or chased away after a false accusation of rape. It took next to nothing for any modicum of success to be wiped out, especially in the sunshine state.

I originally intended to include stories about three grocers lynched in Memphis, four miners in Virginia, and a soldier in Mississippi, but I think the point has been made. Having a skill may or may not have increased chances for survival, but it did not equate to success simply because the State of Florida said it. The powers-that-be in Florida can’t admit to the accidental or intentional misrepresentation of enslavement and its aftermath. Another generation will get the impression that enslavement benefitted Black people. They really should do better.