I want to believe I grew up in an unprejudiced family, but I know it’s not true. My mother and aunts, when they spoke about Black people at all, tried to be charitable, but they also were patronizing. “They’re good people,” they’d say, or, “The ones we knew in Arkansas were always good to us.”

On the other hand, their brother, my Uncle John, probably would be called a white supremacist today. The language he used about Black people was disgusting, but it wasn’t uncommon on St. Louis’s South Side, which, unlike North St. Louis, remained overwhelmingly white until the 1970s and 1980s.

I also want to believe my mom and dad left North St. Louis for reasons other than the white flight that accelerated in the early 1950s. When I was five, we bought a home in Soulard, an old South St. Louis neighborhood that only decades later became gentrified. It was the location of our family’s grocery store.

The restrictions on my movement around St. Louis bore the greatest witness to the racism in my family. When I was young, using city buses to get around town, or when I was older and started driving, my mother forbade me from venturing into North St. Louis and even more strongly into East St. Louis, across the river. “Stray into the wrong neighborhood, and you could be beaten up or killed,” she warned.

I suspect Black kids heard similar warnings about venturing into South St. Louis or the wealthy West County suburbs. That’s how racial distrust gets passed down from generation to generation. And maybe, as they create fear, some of these warnings become self-fulfilling prophecies as people pervert the Golden Rule into “Do unto others before they do unto you.”

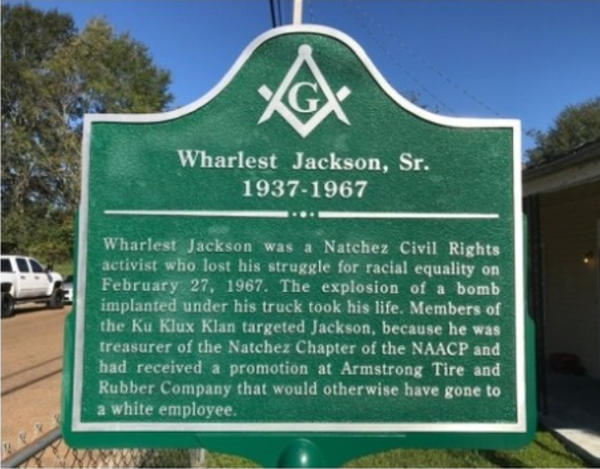

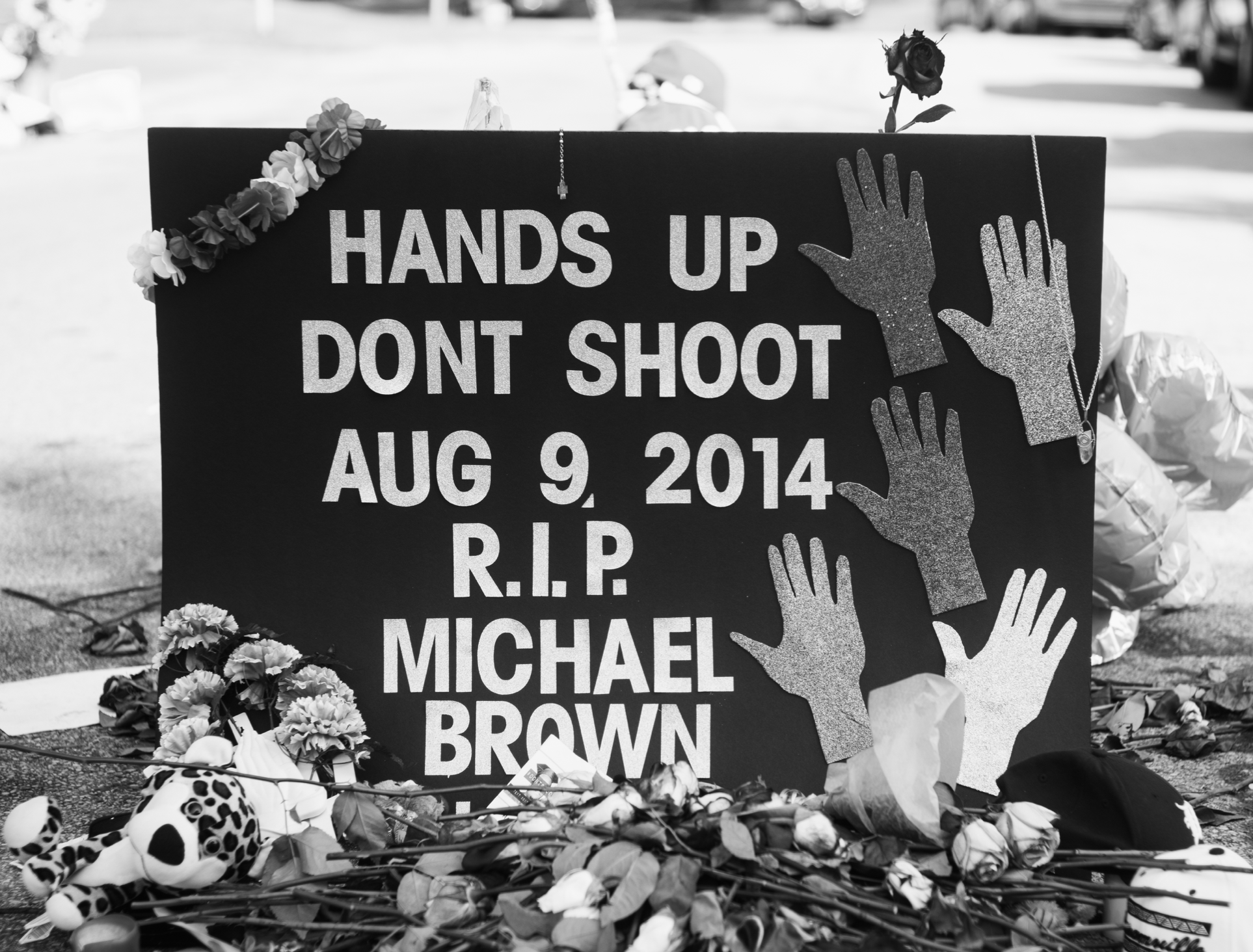

Most recently, St. Louis put its racial tension on display in 2014, when the pressure cooker blew its lid in Ferguson. People still debate whether white Officer Darren Wilson, 28, was acting in self-defense when he shot and killed Michael Brown, an 18-year-old Black man. The incident sparked riots and months of protest.

I’m a product of the school system created by The Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod, a denomination based in St. Louis but operating throughout the world. Its founders came to Missouri from Germany in the late 1830s.

In grade school, when my teachers discussed racial and ethnic prejudice, they spoke about slavery and the Civil War but even more about World War I and American prejudice toward Germans. Specifically, they talked about how vandals threw bricks through the beautiful, stained-glass windows of Gothicchurches built by Germans in both North St. Louis and South St. Louis.

As early as 1877, the denomination initiated an active ministry to Black Americans. Shortly thereafter, St. Paul’s Colored Lutheran Church opened in Little Rock.

By the 1920s, the Synod was operating Alabama Lutheran Academy in Selma and Immanuel Lutheran College in Greensboro, North Carolina. Both schools trained Black teachers for Missouri Synod schools, and Immanuel also served as a seminary for Black pastors. I can’t say whether this was an extension of the “separate but equal” mindset, but as Martin Luther King, Jr. once observed, 11:00 a.m. Sunday morning may be the most segregated time in all Christian America. I know that, growing up, I never attended church with a Black family.

At Lutheran High School South, my high school, we had only two Black students during my four years there. One graduated, but the other left after only a year. Black students comprised about a quarter of the student body at our sister school, Lutheran North. Chuck Berry sent some of his children there.

In the fall of 1967, I entered Concordia Teachers College in River Forest, a wealthy Chicago suburb. A small contingent of Black, synodically trained students had made their way there, as well as a young Black English professor, Thomas Penn Johnson. We were just six-and-a-half years apart in age, and we became good friends.

Thomas, who grew up in Greensboro, had been on a path to become a Lutheran pastor before he came to teach at Concordia. Immanuel had closed by the time he began ministerial studies. Thomas started at Concordia Seminary in St. Louis in September 1967, the day after he completed the oral defense of his thesis for a Masters in English degree from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

The congregation’s leaders . . . in effect were saying, “Communion wafers touched by Black hands will never touch our lips.”

When he came to Concordia-River Forest, he had suspended his studies at the St. Louis seminary. He never returned. I didn’t learn why until he told me the whole story some years later.

As part of their training, the seminary assigned students to do field work at congregations throughout the St. Louis region. Thomas was sent to Peace Lutheran Church, an all-white congregation in the South St. Louis suburbs. He was not greeted with open arms.

The congregation’s leaders told the seminary they would accept Thomas, but he wouldn’t be allowed to help administer communion. In effect, they were saying, “Communion wafers touched by Black hands will never touch our lips.”

Concordia hid the congregation’s reason for its actions from Thomas until one professor, ashamed of both the congregation and the seminary, informed him of what had happened. At that point, Thomas needed time to assess whether he wanted to serve as a pastor in such a church body, and Concordia-River Forest gave him some shelter while he thought things over. Ultimately, he remained Christian but left the Missouri Synod. He had a long, successful career teaching at a community college in Fort Myers, Florida.

Later, I also left the Missouri Synod, which grew increasingly narrow-minded after a group of conservatives took it over in the late 1960s.

I enjoyed a good, cordial relationship with the Black students at Concordia-River Forest. My senior year, when several of them wanted to go the Black Panther headquarters on Chicago’s South Side, they asked me to drive them. Once inside, some of the members frisked me, and they kept an eye on me, but I never felt uneasy. My fellow Concordians vouched for me, so there were no real issues.

In 1973, a faculty member invited a couple of Black students and me to his home for lunch. During the meal, we enjoyed a platter of sandwiches, some potato chips, and good conversation. Afterward, one of the Black students, Oliver, noticed a checkerboard and invited me to play.

I truly respected Oliver. He was an outgoing and excellent pianist, and, I discovered, an accomplished checkers player.

It seemed like no big deal. I’d played the game since I was a kid, usually against my sister, and I thought I understood it well.

It soon became apparent that there was more to checkers than I imagined. After not too many turns, Oliver converted several of his pieces into kings and wiped me out in front of our host and our friends.

These things happen, I thought, and I asked him to play a second game. Again, Oliver slid a piece here, jumped a piece of mine there, and wiped the board with me.

I asked for another game, doing my best not to show I was seething inside. The third game unfolded like the first two. When I was near my third loss, I thought:

“My god, I’m being humiliated by this . . .”

That hateful word, the “n” word, the word that so disgusted me when my uncle used it, came bubbling up in my brain. I never voiced it, but I immediately learned something ugly about myself. My lid had blown, and I felt ashamed.

I often replayed this moment in my head for weeks after it happened. Nearly fifty years later, it still haunts me. It keeps me humble, and it makes me realize how racism can assert its hold on me, even when I believe I’m free of it.

Few of us, regardless of our background, have reason to feel smug about our understanding of racial issues. If we believe we are free of prejudice, I think we’re not being honest with ourselves.

Confronting our prejudices and our fears means listening in our heads for knee-jerk stereotypes to bubble up, and then resolving to reduce our tendency to let them influence our actions. It means expanding the kinds of artists and writers we pay attention to — in my case, not just F. Scott Fitzgerald but also James Baldwin, not just C. S. Lewis but also Cornel West, not just Harper Lee but also Maya Angelou, not just Paul Simon but also Jay-Z. It means being more vocal in challenging friends who casually spout off misinformation about how Muslims are overrunning Europe and illegal immigrants are destroying America. Also in my case, it means stepping out of my bubble-wrapped neighborhood, my bubble-wrapped church, and my bubble-wrapped friendships to a broader, more expansive world.

I know how ignorant I am on this issue, but I have a hope, in St. Louis and elsewhere, that we can acknowledge our prejudices and fears, talk about them, and take a few steps toward one another. If we don’t, the lid will blow, again and again, and why should we be satisfied with such a mess?