I first learned about the racial caste system created by Jim Crow laws during the late 1950s. I spent most of my young life in my hometown, St. Louis, but each summer, my younger sister, Joan, and I would travel to tiny Cash, Arkansas — Population 141, according to the signs posted at each edge of the town’s only paved road.

As one family member or another drove us south into Arkansas, our surroundings changed from substantial brick homes, well-stocked grocery stores, the massive Anheuser-Busch brewery, and a world-famous zoo to dilapidated clapboard shacks, rundown general stores, grain elevators, and cotton fields. St. Louis’s oppressive heat and humidity came along with us, and as soon as we arrived, a horde of Cash’s town mascot, the mosquito, started sucking our blood as enthusiastically as a wine connoisseur samples a fine Merlot.

We went to visit my Aunt Ruth and my country-doctor grandfather, J. H. McCurry, who practiced medicine until he was 94 years old and lived to be 106. We enjoyed their company well enough, but before long, we city kids would go stir crazy.

To give us a brief respite from the agonies of small-town living, our much older cousin, Jack, drove us once each summer to Memphis, about eighty-five miles southeast of Cash. He had become one of several surrogate fathers to Joan and me after our dad died in 1957, and he knew how to entertain little kids.

On our day trips, Jack would treat us with a visit to Lakeland, a small amusement park where I had my first corn dog. We’d go by Elvis Presley’s home, Graceland. Members of the singer’s Memphis Mafia sometimes handed out autographed photos at the mansion’s gate, which featured two stylized, wrought-iron likenesses of a hip-wiggling Elvis, holding a guitar. And, when I was nine or ten, Jack took us to a downtown Woolworths.

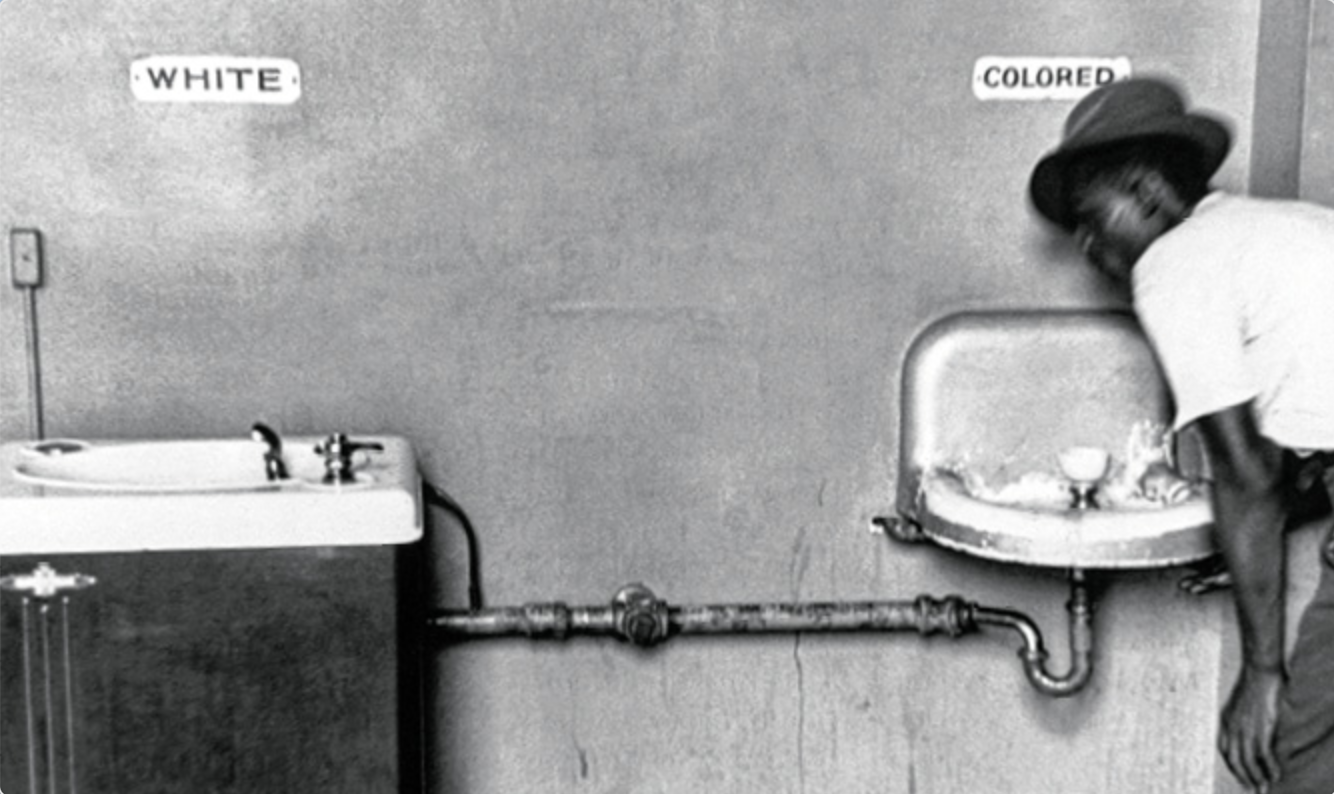

The store felt familiar. Just like the Woolworths stores I knew in St. Louis, this one had racks of toys, display cases of costume jewelry, ceiling fans, and a lunch counter with red vinyl, steel-backed swivel seats bolted into the floor. Everything was the same as in St. Louis, until Joan and I sought out a drinking fountain. We eventually found two fountains, each made of porcelain, situated side by side, but separated by several feet. Scrawled in soap on the mirror that spanned the wall above them were two words: “White” and “Colored.”

In the mirror, I could see Joan looked as puzzled as I felt. I also saw Jack standing behind us, thinking over how to give us some direction. Finally, he said: “Just drink from the one on the left.” We did, and then we walked out of the store.

On the drive back to Cash, Jack told us a lot of white people in the South looked down on Black people, not wanting even to touch them or anything they touched. “We don’t believe that,” he said. “Granddad treats all his patients the same, whether they’re Black or white or whatever color. They’re all people just like us.”

Other than to say we thought it was stupid, Joan and I didn’t pursue what we had seen. But with as much smugness as a young boy could muster, I remember thinking St. Louis was so much better than Memphis when it came to treating people right. I hadn’t really been aware of racism before, but once I was, I believed my hometown had avoided it. We, after all, didn’t have separate drinking fountains in our stores.

I hadn’t yet learned that enslaved people had been auctioned less than a hundred years earlier at the Old Courthouse, just two and a half miles from my boyhood home. Or that, in the same building, in 1846, the enslaved Black man Dred Scott launched his bid for freedom, taking his case all the way to the United States Supreme Court — where he lost. Or that, in 1917, just across the Mississippi River in East St. Louis, mobs of armed, white, striking factory workers, concerned that their jobs were being stolen, burned the homes of an estimated 300 Black families and beat, lynched, and shot Black residents, killing an estimated one hundred of them. Or that, both in my boyhood and now, St. Louis can be a racial pressure cooker, and people shouldn’t be surprised when the lid blows.

By 1949, St. Louis’s Black and white residents sat next to each other at baseball games, in streetcars, and at the Municipal Opera, a large, outdoor amphitheater that produces Broadway-style musical theater. In most ways, however, the city reflected the realities of America, struggling with the increasing pressures of the Civil Rights Movement, which was picking up steam.

Statewide, Missouri still segregated its schools and prohibited interracial marriage. For the most part, Black and white customers ate at separate restaurants and slept in separate hotels. And in St. Louis, they swam in separate pools.

The city’s Fairground Park, in the summer of 1949, contained what may have been the nation’s largest public pool, bigger than a football field and capable of accommodating more than 10,000 swimmers a day — 25,000, by some accounts. The pool took sixteen lifeguards to patrol it.

On June 19, 1949, a St. Louis suburb, Webster Groves, opened a new public pool and denied entry to Black residents. A reporter asked John J. O’Toole, St. Louis’s director of public welfare, whether Black residents would continue to be barred from the city’s traditionally whites-only pools when they opened two days later. He responded that all the city’s pools would be open to all comers.

O’Toole’s intentions were noble, but his planning and execution fell woefully short. He appeared to assume integration would be accepted matter-of-factly and without incident.

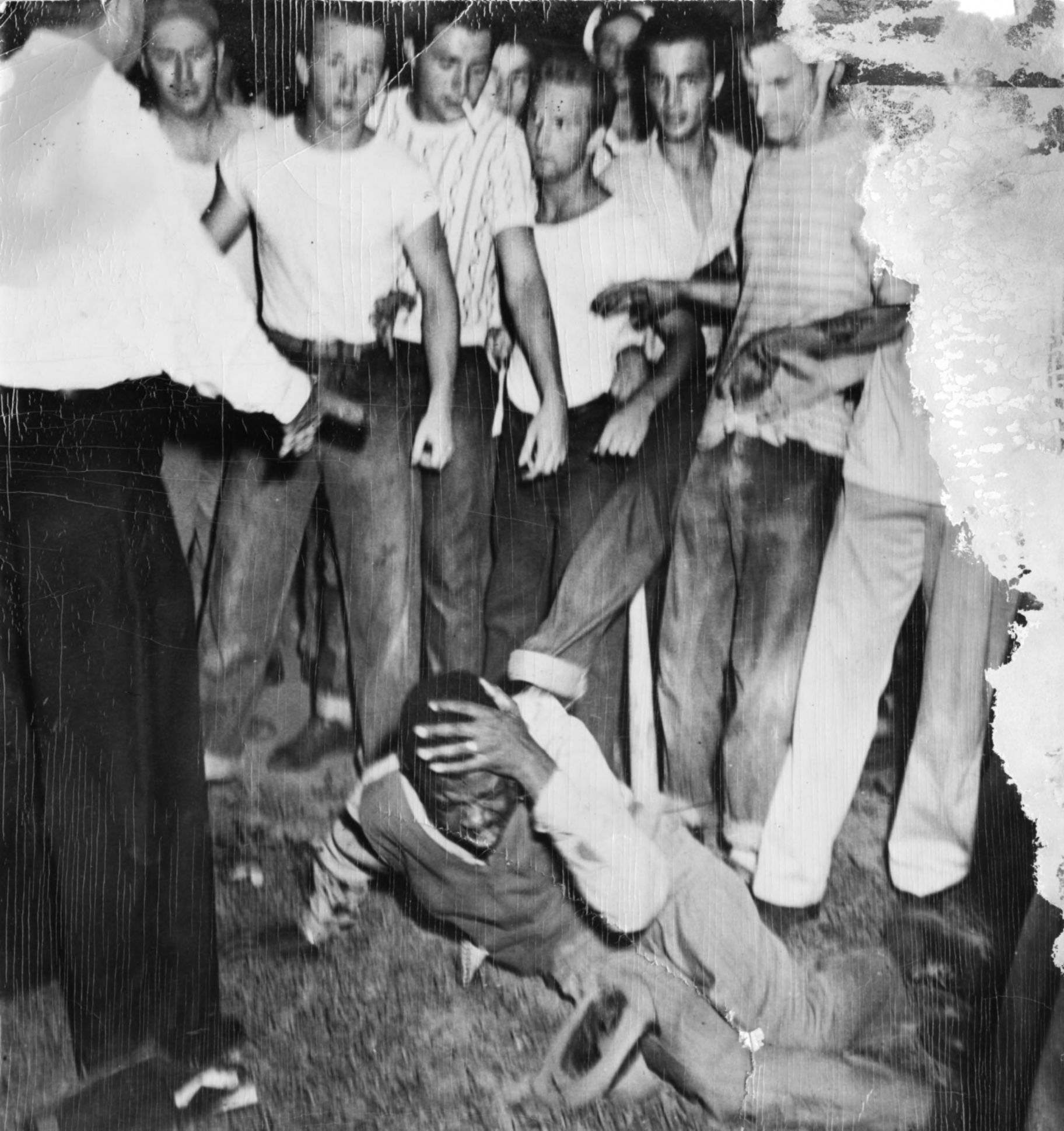

On June 21, several hundred youths came to swim at the Fairground Park pool, and thirty to forty were Black residents, according to media reports. The swimming went smoothly enough, but outside the pool, about 200 white teenagers gathered at the fence and shouted threats at the Black swimmers. White adults soon joined them. When the first swim session ended at 3:00 p.m., a custodian led the Black swimmers to a dressing room, and a police escort was arranged for them.

Sixty years later, Robert Gammon, one of the Black swimmers, recalled the white crowd’s pounding on the dressing room door. As the police led the Black youths away from the pool, some members of the white crowd struck some of the Black swimmers. The police reportedly did nothing to stop them. Gammon recalled being spit on by a white woman, and he said a friend of his was hit on the head by a brick thrown as they ran away.

By dark, the crowd had grown to about 5,000, and more than a few white people carried broomsticks, baseball bats, bricks, pipes, or knives. Media reports indicated at least fifteen people were injured, including two with stab wounds. Ten of the fifteen were Black. It took more than twelve hours and more than 400 police officers to restore order.

The mayor of St. Louis immediately declared the pool segregated once again, but the courts eventually ordered it and other St. Louis pools integrated. In 1956, the pool closed after attendance plummeted. For the most part, white swimmers had stopped coming.

When the Fairground Park riot happened, my mother was pregnant with me. I was born in December 1949, and I was brought home to a four-family flat less than two miles from the pool. Surely my folks knew all about this, and knowing my mother, she had to have been afraid with so much calamity occurring nearby. The crowd noise probably wafted over to our home. But I never heard a word about it from her or anyone else.

The St. Louisans I grew up with revel in the past, which I think indicates they believe the city’s glory days are behind it. The stories they tell are about the launch of the Lewis and Clark expedition from St. Louis; the building of the innovative Eads Bridge, which opened in 1874 and still stands today; the creation of the Anheuser-Busch brewing empire; the glories of the St. Louis Zoo; the incredible engineering of the Arch; the storied history of the baseball Cardinals; and, the Greatest St. Louis Story Ever Told, the wonders of the 1904 World’s Fair.

My white St. Louis friends rarely talk about the future, and they almost never talk about race issues. When I informally polled my St. Louis Facebook friends about whether they knew about the Fairground Park incident, thirteen said they never heard of it, three said it vaguely rang a bell, and one said she learned about it only as an adult. Almost everyone who answered was white; one Black woman was among those who were unaware. I myself knew nothing about the Fairground Park riot until recently.

St. Louis, to this day, is one of the most segregated cities in the United States. I suspect the Black residents of St. Louis talk much more about race than my white friends and I do. Their lives are defined and delineated by the racism they experience; ours are not.

On second thought, that’s not true. Our lives are defined and delineated by the white privilege we enjoy. We just don’t realize it. And we fail to see what it costs others.

Member discussion