As a Black Britain growing up in the 1980s, I can confidently say microaggressions were and still are accepted today as a way of life. In some respects, I am thankful they are not an overt or physical demonstration of racism. But in other ways, those aggressions can be just as damaging — they are a constant hurtful reminder of how I am viewed despite my character and all I’ve achieved.

It is a sad indictment to say that because of where I lived. Growing up with racism is something that you, and sadly also those who are not directly affected, accept for what it is. It is an even greater tragedy to say that today, in 2020. There is still a need to write about a problem that affects so many globally.

A burden that can be shared

My heart is heavy and full of mixed emotions, and I am burdened to recount one experience that I had buried within an unfortunate vast catalogue of racial encounters.

I have mixed feelings because I know to dwell on racial experiences I’ve come up against serves me no good. But over the past few weeks, I have devoured numerous accounts from highly accomplished writers who are brave enough to share what they think and who have poured their hearts out to the world. I would be a hypocrite if I applauded their bravery but avoided sharing my own story. I am especially moved to tell my story because I share the same anger at the blatant injustices and brazen hypocrisy in a supposedly “free” world.

But still, I am reluctant. Perhaps that is because the root of my mixed feelings arises from the consideration of my experiences. I know they would rightfully appear trivial against the backdrop of what many People of Colour endure each day. But I now appreciate such dismissal of my experiences as a misguided point. We are wrong to trivialise any form of racism. We shouldn’t scale what is right and what is wrong; there is no competition. An injustice is an injustice!

I now recognise the years of suppressing, of disregarding how I feel and of taking on the burden of keeping the peace, are part of the problem. While ignoring encounters provides a path of least resistance and a way to function unnoticed, such a way of survival ultimately robs us all of a chance of dialogue, a chance to change.

A chance encounter

It all started back in the mid-90s with a chance encounter in a local supermarket with parents of a school friend.

For a time while growing up the parents were our neighbours until they moved to a different house. I was fortunate enough to remain school friends with their daughter. In meeting many years later after graduating from university it was a pleasure to be able to reminisce over being one-time neighbours.

As we swapped stories about family, my friend’s parents made a kind offer by outlining an opportunity to earn an income even as I was applying for my main job. It merely required me to attend an evening of drinks, find out what was involved, and then decide whether to become involved. How could I refuse? I had nothing to lose, and besides, I had trusted and known my friend’s parents for a while.

The prelude

The evening started pleasantly, with drinks, snacks, and polite, relaxing conversation. Our hosts were our former neighbours’ recently married daughter and son-in-law. They did a fantastic job to make each of us feel welcome. The room was filled with parents’ pride over their daughter’s recent marriage and excitement over the opportunity we were about to discuss.

I remember feeling honoured to be invited and amongst a group of people who were about to positively change their lives. Despite my nervousness at meeting new people in an unfamiliar setting, it never really occurred to me that I would need to be on my guard. My focus was on the possible income stream.

The microaggression

It was after the presentation, of which I can’t remember the details, that the evening took a disappointing turn. The presenter, an older, well-respected gentleman, started the conversation with me and several others on why he thought Black sportspeople dominated certain sports. The topic of athletics and sprinting, both close to my heart, became examples. Immediately I thought about why this subject, why now?

He reasoned it was because of Black physiology — Black people had a distinct athletic advantage. In his words, which I am paraphrasing, enslavement was the cause for a natural selection of the strongest and fittest which gave today’s Black athletes, descendants of the enslaved, an unfair genetic advantage.

It was because of the physiology of Black people they had a distinct athletic advantage

I grew uncomfortable with the conversation. I remember looking around, seeing the agreeing faces, and hearing the agreeable comments. The presenter put across his convincing thoughts using recent sporting events as evidence. I could understand his argument, but I immediately recognised why we were having this conversation. I didn’t like it, and I didn’t like the situation.

The subtlety that breeds doubt

Unfortunately, as I look back now, I conclude it was a mistake to say nothing. At the time, I didn’t feel confident and well-enough equipped to push against the implied racism. Instead, I doubted my own concerns and thought it was easier to be quiet and give the presenter the benefit of the doubt.

Microaggressions are an unfortunate dynamic of moving in white spaces; your radar is always on alert for disappointment and potential aggravation. But at the same time, you live by the unwritten rules of wanting to be accepted and not bring further judgement on the space you rightfully occupy.

Whether you notice it or not, as a Black person moving in a white space a part of you will always be on your guard when meeting new people and in unfamiliar places. It takes longer if you ever do decide to trust.

Even when you do decide to trust as a form of self-protection, you are constantly fine-tuning and adjusting your radar so you can detect who and what may be becoming your way. It may be their wry smile, reduced eye contact, or one of the various body language signals you become accustomed to detecting. It can all be exhausting, but you know the consequences of getting it wrong can range from a personal verbal or physical attack to exclusion or the injustices we far too often see.

Now for those of you in doubt as to why the conversation was problematic — or who may be questioning why I chose to share a debatable microaggression — let me break it down for you. On the surface, it may seem the gentleman in question had put forward a reasoned argument to solicit debate, but truth is in the timing, and the context told me otherwise.

The gentleman’s conversation highlights the difficulty of navigating white space. Was this a form of covert racism? Was his opinion ignorance on his part? After all, there is no real scientific evidence to back up his line of thinking. Or was this curiosity honestly expressed to extract my perspective as the sole representative of the Black race? I don’t know the answer, but I know the indignation I subsequently felt after hearing the classic example of biology as the reason for Black success.

Microaggressions are an unfortunate dynamic of moving in white spaces; your radar is always on alert for disappointment and potential aggravation.

As far as I am aware, People of Colour do not have a gene or genetic advantage. Yet there are those in and outside the scientific community who have concluded because it serves them well to dismiss any understanding of the circumstances as to why there appears to be dominance. There are many factors at play, such as motivation and belief; success breeds success. People want to be like their idols, the people they see, and so on. Fundamentally as any elite athlete knows, it takes determination and hard work.

In case you are wondering, I said no to the income opportunity!

Personal reflection

On the surface, microaggressions may seem harmless when compared to the violent acts of racism we sadly have become accustomed to seeing. Because of their nature as small and often unnoticed digs, it is all too easy to dismiss them, but they are a hidden precursor to a slow and premature death.

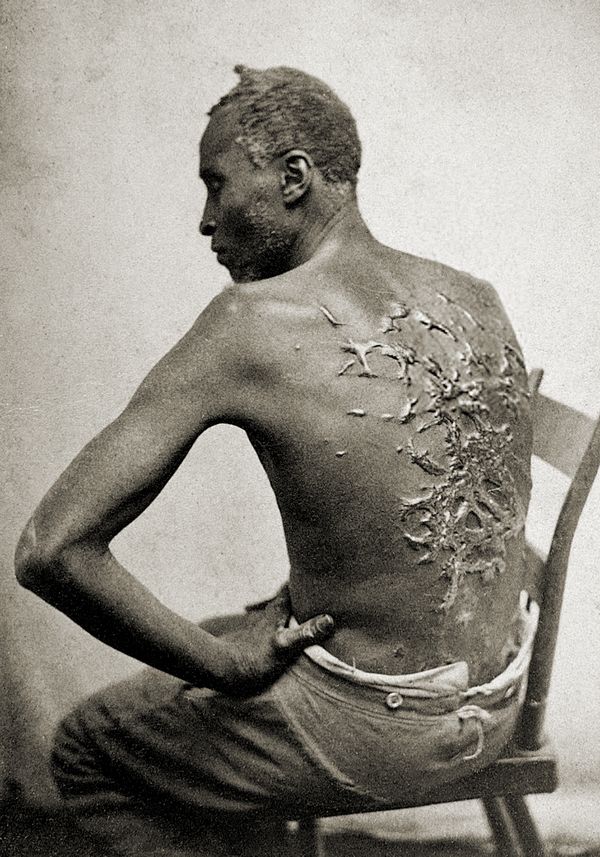

Each microaggression may go unnoticed to the aggressor or mean nothing more than an opportunity to reveal misguided and deep-rooted thinking. But to us, as People of Colour, we feel every one of them as if we are compelled to endure death by a thousand cuts. It’s not the first, second or tenth cut that kills you. It’s the accumulation of the wounds and weight of the uncertainty you carry over time that does.

Older and wiser now, I am less tolerant of any form of bigotry. I understand we all have a part to play. Speaking up is important not just for ourselves but for all parties involved. When I think of my parents who immigrated to Britain in the late 1960s and the first-generation racism they endured, I recognise it is incumbent on me to speak for my own generation as well as future generations. Because just like my parents experienced and navigated a path so that I may have opportunities, I know I should do the same for my sons and sons’ generation.

The demonstrations, protests and conversations following the death of George Floyd have further opened my eyes to how little I know about social change, history and the inequalities many People of Colour face. I thought my first-hand experiences were enough! But sadly, no; I need to continue educating myself and adjust to what I hope will become a new and better normal.

It’s in the difficult conversations where truths from all sides are revealed. If that means educating and supporting each other, then we must do so; otherwise, we will all continue to walk the tightrope between how we feel, what we do and what we know is right.

No one has all the answers, but I believe if we start with sensible conversations together, we can find them.