White people may never know what it’s like to be Black, but I do. And as long as I have breath in my body I will talk about the impact of racism, white supremacy, and microaggressions on Black people. White people believe we are in the early phases of a race war here in America. For Black people and many People of Color, every day is a race war. It’s the war we can’t seem to win. As long as there has been an America, there have been problems surrounding race. We can put men on the moon, but we can’t put an end to racism and white supremacy?

Microaggressions are the crimes, impediments, and abuses committed by white people and People of Color because they dislike the color of a person’s skin or they’ve deemed certain racial and ethnic groups inferior to their own. Microaggressions help keep racism alive and thriving by maintaining the white supremacist social order that allows all white people and white-passing People of Color to practice racism regardless of their socioeconomic status.

Most people are aware of the blatant racism Black people experience on a daily basis, like egregious police killings, incidents of police brutality, and the idiotic, racist things average Karens or Chads say and do that make the news.

But microaggressions are more subtle and a lot harder to detect. I’ve experienced countless microaggressions during my lifetime. I wanted to share a couple of them to help white people understand how racism works and what it looks like. Trust me. Racism is more than wearing Klan robes or saying the N-word.

My Experience with Microaggressions

A few years ago . . . I’m standing in line to buy my groceries. There is a white female customer in front of me and one behind me. The white cashier smiles as she checks out the female customer. The two white women exchange pleasantries as the transaction nears completion. The cashier gives the customer her tally; the customer gives her cash. The cashier accepts the cash and places the customer’s change on the palm of her hand. The white cashier wishes the white female customer a wonderful day as the woman pushes her grocery cart away.

When it’s my turn, the once-jovial white cashier doesn’t make eye contact with me, nor does she give me the same friendly greeting she gave the white customer before me. After the cashier rings up my order and gives me my total, I hand her my cash. She pulls out her pen and marks my money to make sure it’s not counterfeit. She even holds it up to the light to look for signs that the money isn’t counterfeit. She puts the money in the drawer, and pulls out my change. I extend my hand to receive it, and she puts my money on the counter so she doesn’t have to touch me.

I tell her I didn’t give her the money on the counter, and I want her to give it to me the same way she gave it to the white lady who was ahead of me in line. She digs in. I dig in, too. The white customer behind me sees the entire incident and says nothing. It’s my word against the cashier’s. I take my money and leave.

I filed a complaint with the store. They called and apologized, but that was no remedy for the humiliation and disrespect I received. It was another in the hundreds of scars I’ve received stemming from racism.

I never went to that store again.

This is not an isolated incident. Cashiers and service people intentionally treating Black people differently than they treat white customers happens all the time. The grocery store cashier used her minor cashier powers to show her distrust of my Black skin, all the while knowing nothing about me. That cashier treated me as if I was a criminal who came into the store to commit a crime. It’s one of thousands of humiliating memories I’m forced to live with.

Throughout my sons’ public school education, they’ve always experienced problems with their white female teachers and coaches. Most of the teachers had preconceived stereotypes about Black males and would speak to them—and me — in ways that led us to believe no one cared about the education they received because they were Black. The educators would say all sorts of negative things to my sons, even asking them how they could get into the classes with the smart white kids. The inference was that Black people aren’t supposed to be smart. They ignored the fact that institutional racism was too busy blocking access, under-funding our schools, and making sure Black people weren’t in their spaces.

There were several times over the years when my sons were in public school that I had to take off from work to defend them. I don’t pretend my kids were perfect because they were kids, but in elementary school my kids were coming home crying because white teachers were belittling or singling them out for mistreatment in front of their white classmates. My sons held it together so as not to show emotions in front of their peers because it appeared their white classmates did not have empathy for kids with Black skin. Teachers also flippantly tossed around negative Black student-athlete stereotypes. Those tropes harmed my children’s psyche and self-esteem for a season. I eventually had to complain to the principal, who basically did nothing. Why do white people take jobs to help kids only to tear them down?

Another microaggression my children and I experienced took place when a white high school guidance counselor told me they had filled certain advanced classes when my kids were trying to get into them. Each year my kids and I sat down and mapped out classes based on their individual career paths (Dentistry and Business/Hospitality Management) and attempted to align those paths with the proper high school courses in order to prepare them for transition into college. Each year my kids never got the class they wanted. My kids started telling me all the white kids got into all the good classes, leaving our kids with the scraps.

I marched up to the school like the protective mama bear that I am, and I called a meeting with the white principal and the white female guidance counselor to complain about the process and how the guidance counselor appeared to be excluding qualified minority and non-white children from advanced-level learning which hurts their high school transcripts and prevents them from getting into the colleges of their choice. I threatened to call the U.S. Department of Education if they did not fix the problem, and I let them know that I knew people who worked in Washington, D.C. at the Department of Education. They knew I traveled to D.C. on business frequently; now they learned why.

After that, things changed for my sons.

My sons finally got into advanced-level classes, but they missed a full year of advanced learning and dual credit-opportunities because a white woman decided she was the God of Education and only white kids should have advanced courses. It taught me to stay on top of the things white people do, and I informed my Black friends who were having similar problems. The superintendent got rid of the counselor. We all liked her, but she was nice and wicked at the same time. And still, white people don’t quite understand how they can be nice to us and evil at the same time.

I later joined the school improvement council, the district’s accreditation board, and district strategic planning to make my face known. I also shared my views with the superintendent regularly.

White people often wonder why we don’t perform better, but they fail to recognize their active role in withholding education privileges so that only white people can access the good shit. I had to work on soothing my sons’ wounded souls because to them it seemed we were always fighting with white people about something they believed only white people were entitled to.

As a mother, I was emotionally drained from the realization that someone wakes up every day and comes to their job, a place meant to help kids learn, with intentions to harm them. And she got away with it for a long time because she deemed our kids inferior. That white counselor decided that only white children should have access and better opportunities. Had I not been the fighter I am, my kids might not be where they are today. It’s taxing being a Black man, woman, or child in America.

Invisible to the Naked Eye

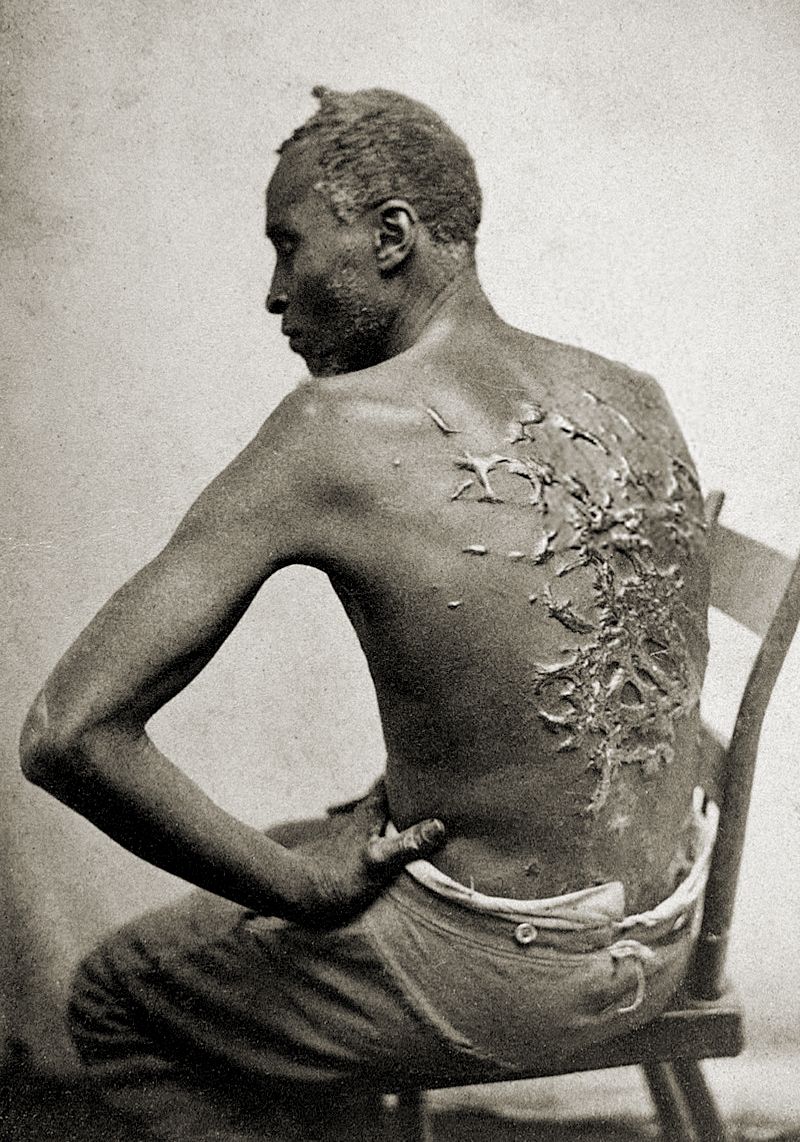

Today’s microaggressions have the same effect on Black people for trying to live their lives as whippings did on enslaved people for trying to escape to freedom. They serve to remind Black people where some white people think our place is in American society. Microaggressions leave scars, just as those whippings left scars. Today’s scars are underneath our clothes and our skin, invisible to the naked eye. While scabs may grow over our old wounds, we never forget the person or incident that caused our injuries.

It took seeing the photo for Northerners to see that slavery was wrong and to end it. The same problem exists with microaggressions. It takes white people so long to see, and it takes so much evidence, usually evidence that we’ve physically experienced, before they believe us. White people need to begin assessing their own roles in acts of microaggression against Black people. They should also ask themselves why they require so much evidence—so much violence, so many injuries to Black people — before they believe they are harming Black people? That in itself is a specific form of microaggression.

Is it because you subconsciously think we really are subhuman?

Is it because you need for all doubt to be removed before you’ll believe us?

Start believing Black people the first time we tell you something.

Look at yourselves and stop asking us to prove what you already know is true.

Allowing evil and racist white people to get away with harming us is a microaggression, so call out white people committing racist acts. Report them, tell crime reporters, make anonymous tips, file workplace grievance on employer biases and discrimination, and stop people from physically injuring us. Racism thrives when white people remain silent and ignorant.

White people asking Black people and People of Color to be patient and kind as we experience racism every single day is insane and another type of microaggression. Stop focusing on your feelings and start worrying about how we feel. We don’t feel good. Asking us to be patient while we’re being abused with microaggressions is disrespectful and lacks empathy. Center us; we’re the people who need your attention the most.

Also, white people expecting demonstrations against police brutality and standing up for equal treatment to be over soon because you want things to get back to normal is a microaggression because it says to us your comfort is a higher priority than addressing systemic racism, so learn how to be uncomfortable. Black folks always have been uncomfortable in America.When you’re uncomfortable, things get better for us. We make progress. Black people can finally see change.

If you want to help Black people, help us by educating yourselves on all the ways white supremacy ruins Black lives. Figure out how to deconstruct and remove the systemic racism that exists in America.