I’ve long thought that white privilege is an unfortunate choice of words.

Of course, it’s accurate to anyone who understands the term—which is to say, mostly Black people. For the average white person, which is to say many, the word “privilege” conjures up the Kardashians. Paris Hilton. Yachts and gold fixtures and the Amalfi coast. Perhaps that’s a bit extreme but suffice to say most of us white folks don’t feel “privileged.” We’re often so busy looking up, though, and being envious of what we don’t have, we fail to look around at what others don’t have. And we’re so self-centered, so quick to deny, that we fail to realize white privilege very rarely has anything to do with money.

To my fellow white readers, a quick quiz:

Have you ever been followed around in an average store because the clerk was sure you were going to shoplift—not because you ever have, or aren’t dressed well, or act suspicious in any way, but just because you’re white?

Have you ever had to sit through a job interview where everyone else in the company was Black, knowing that they were all wondering how you could ever fit in and quite possibly looking for a way to disqualify you, but having to act as “normal” as you can?

Were you ever pulled over for a busted turn signal (or nothing at all), then told to get out . . . had your trunk searched . . . handcuffed while you waited, wondering if you’d survive if you moved even slightly? (I’ve been pulled for speeding several times, but—none of that.)

Did you work your butt off to earn great grades and get accepted into a top college, only to have most of the other kids assume that you got in solely because of your race?

. . . white privilege very rarely has anything to do with money

Then there’s the realtor in Detroit who was recently handcuffed along with his client and his client’s kid, because the neighbor thought surely they were breaking and entering. Has that ever happened to you while house hunting? And were you then offered a subprime mortgage loan despite a solid credit rating?

Been arrested for not ordering quickly enough at a Starbucks?

Worried every single time your child walked out the door that he might not make it back in?

Have you ever been in a room full of Black people (rare for too many of us white folks) and felt like you had to worry about how they perceive you because you’re white—as if everything you said and did could affect their opinion of all white people?

Now, one of us white folks might have had that one weird incident that one time, or we know someone who had one, but they’re certainly not the norm. We might worry about someone else’s race, but we never worry about our own or even give it a second thought.

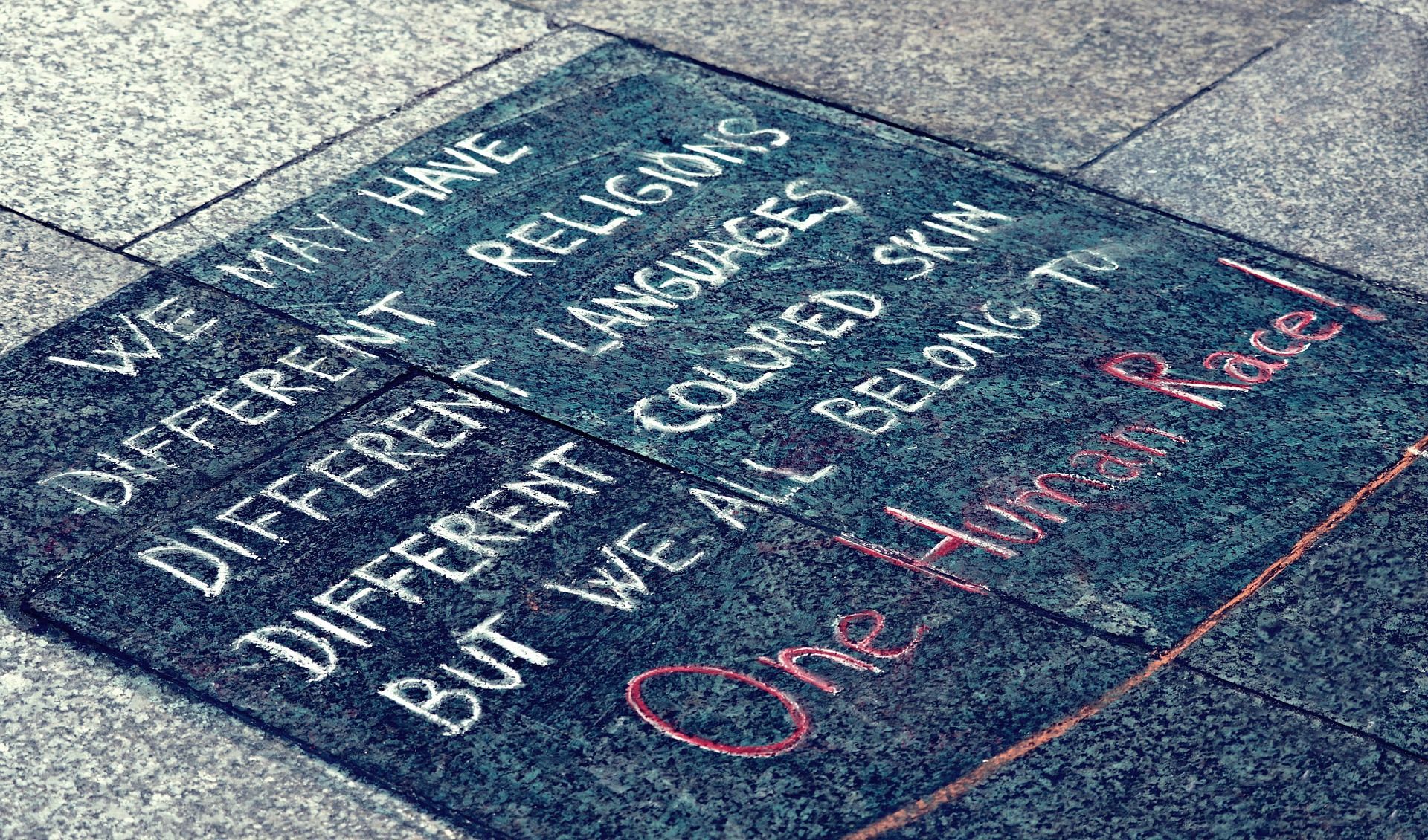

White is simply invisible. We don’t actively think of ourselves as white; we don’t even use the adjective. We refer to “the man,” or “the Black man,” or “the brown man.” See how that works? The fact of the matter is, whether you’re rich or whether you’re poor, regardless of what else you have to worry about, the white person will never have to worry about their race being a factor—and that, in a nutshell, is white privilege. You might not have that yacht, but everything else being equal, you still have it better than the Black man standing next to you who has to worry about all of those things simply because he was born Black.

Then, because we can ignore our own race, we white folks tend to make all sorts of assumptions about other people as if their situation is similar. Why doesn’t he just get a job? Why didn’t she just do what the cops told her to do? Why don’t they try in school? Why why why . . . and then because we can’t understand our white privilege, we decry them “making it about race”—in essence, us then making it about race. And so racism perpetuates, even among the best of white people.

These moments I refer to, which we white folks might remember that one time about, is the reality every single day for our Black friends. They must always carry that awareness with them, they must constantly be reading the thoughts and movements of the white folks around them because things can change in a moment. Any moment, the other shoe can fall . . .

If this is the every-day-life of a Black person in America, what must an extreme look like? How are Black and white America responding differently to the pandemic?

Certainly, there is what we see in the news, which is mostly about white people often acting, well, stupid in the face of a highly contagious and deadly virus. A large percentage of us are living our best lives as if the dear lord will surely protect us because—well—he always has. At least that would be the way we see it. Roughly half of us, maybe more, are okay with skipping the vaccine, asserting our right to go without masks, attending weddings en masse, and insisting that the bars remain open. Diseases are for other people and capitalism must carry on, yes?

This isn’t to be flip or say that none of us has suffered (and certainly quite a few of us have died), but the government and our ecosystem have surrounded white people with the same giant safety net and aura of invincibility that it typically does in times of crisis—work from home, learn from home, don’t worry about eviction, get your food delivered, count on the healthcare system to save us. We are not grateful for this support, we expect it. Imagine our great surprise when people we know actually get sick. When people we know die. The news and the ICUs are filled with white people on ventilators saying, “If only I’d known it was real.”

My Black friends have been a lot more circumspect.

Black people, who have gone from enslavement to Jim Crow to systemic racism and for many of them poverty, have few expectations of a giant, warm, fuzzy safety net. That safety net is essentially a giant, warm, fuzzy piece of white privilege. Black folks are far less cavalier about their chances of survival, far more willing to wear a mask, hunker down to the greatest extent possible, and support each other. Unfortunately, white privilege steps in to make all of that more difficult, as well.

The average Black family has a net worth—savings for a rainy day, or easter egg, if you will—just ten percent that of the average white family. Part of that is due to less generational wealth (think lack of reparations); another big part is the systemic racism that makes it harder to own a home, which is the biggest way in which most Americans accumulate savings. All of this means that most Black people must work if they wish to eat, and they’re more likely to have jobs that can’t be done from the home. These jobs are also more likely to be considered “essential” in a pandemic—think grocery clerks and Amazon workers—and more likely to require interaction with others.

. . . the government and our ecosystem have surrounded white people with the same giant safety net and aura of invincibility that it typically does in times of crisis

Beyond that, while most of us white folks are grousing about the difficulty of watching our kids in remote learning while we try to work from home, having to go to work means that Black parents often cannot be home with their kids. Cannot ensure that the kids log on, cannot help with technical difficulties, cannot provide the extra support kids need to keep them from falling even further behind.

In single-parent homes, it’s even more difficult. In 2019, this was sixty-four percent of Black families, as opposed to twenty-four percent of white families.

White people also assume some level of healthcare support while a Black person’s relationship with healthcare is more fraught. Obviously less net worth and lower-paying jobs make it less accessible, but beyond that, there is a history across the United States of medical experimentation and sterilization on Black people that has left many wary and unsure of vaccines. And, medical professionals are less likely to take a Black person’s health concerns seriously—particularly a Black woman’s—or provide the same level of care. Even worse, poverty and racism create higher levels of the pre-existing conditions that exacerbate Covid.

As such, a deadly disease becomes deadlier. According to CDC statistics, Black folks are only slightly more likely to contract Covid but twice as likely to die from it.

Think about all that in combination. White people are busy attending weddings and fighting over their right to go maskless and unvaccinated, while Black people are being more careful and yet they’re twice as likely to die. That is white privilege: not private jets, not gold fixtures, but life or death.

Even some of the most progressive white people I know have been known to scoff at white privilege on occasion. “Yeah, I’m just sooo privileged.” (Cue eye roll.) Yes, we are, and we can do better. We must do better. Ironically, our failure to vaccinate ourselves, as well as support impoverished nations, will continue to extend the pandemic and lead to still more variants. So open up your hearts, listen to your Black friends, hear their concerns, understand the downsides of white privilege, and how we can each play a part in building a more equal world. The world is depending on it.