Letter from the Editor

June has been a little crazy. Way too many mass shootings, even as we continue to parse Buffalo and Uvalde, and debate gun laws for the thousandth time. Dead grandparents and dead children haunt my dreams. On the opposite end, we have Pride Month . . . Father’s Day . . . Juneteenth. Sometimes it’s too much, too quickly, and too many directions to reconcile. Sometimes I have to turn off the TV and shut down social for a bit while I find my equilibrium again; I imagine we all do, these days.

Somewhere along the way, though, I saw a brief mention of Black Music Appreciation Month. I hadn’t heard of it before (or in the two weeks since, for that matter). I wondered if President Obama had initiated it, as I’ve enjoyed his periodic playlists on several occasions, but it was in fact President Carter back in 1979. The current White House did apparently offer a nice acknowledgment on May 31st. Conveniently, Queen Bey released a single from her upcoming album just this week.

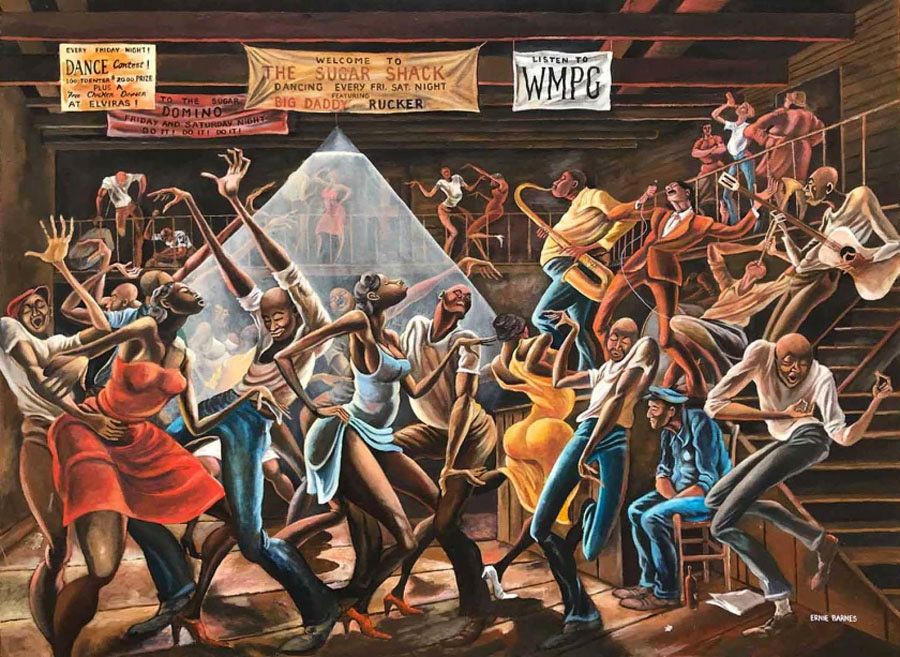

I’ll warn you right now that I’m no history expert, like William Spivey, or a music buff like Jesse Wilson or Tre Loadholt. But I do love a wide variety of great music, from Jazz and the Rhythm and Blues to Rock, Rap, Hip Hop, and more–and I know there are a whole lot of brilliant Black musicians at the root of each. As the Smithsonian states in its Spotlight on African American Music, “African American influences are so fundamental to American music that there would be no American music without them.”

There are a lot of depictions of Black folks singing across the long centuries of enslavement, and I’ve heard tell that plantation owners and such would claim that the singing was a sign of good cheer. Of course, more honest folk know these songs represented a whole wide range of emotions, along with a way to preserve history and heritage, express spirituality, release their sorrows, and provide some healing to survive the most horrid of circumstances. It’s also been suggested that it was sometimes a mechanism for sharing secret information in public situations as a sort of code.

In any case, music was an important part of Black culture long before then in Africa and it continues to be today as it’s stretched across the continents. To hear Gospel music from a Black church choir is to get a glimpse of heaven. Whitney Houston is the gold standard for the national anthem. And everyone’s personal opinions aside, Aretha Franklin is considered by many to be the greatest singer ever.

As the Smithsonian quote suggests, all American music—and its influence across the world—is founded on one form of Black music or another, a relationship that began uneasily with minstrels and has not been adequately acknowledged by the broader white population or sometimes even the white musicians who benefited most from it. Several sprang immediately to my mind, so I did a little research to see if there was attribution.

It would be impossible to deny how much Elvis Presley was influenced by the plethora of popular Black singers of his time—from Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington to Sam Cooke, Otis Redding, Ben E. King, and many, many more. Elvis himself talked about it, saying:

A lot of people seem to think I started this business. But rock ’n’ roll was here a long time before I came along. Nobody can sing that kind of music like coloured people. Let’s face it: I can’t sing like Fats Domino can. I know that. (Newsweek)

Elvis was very popular among Black audiences, and obviously the 1950s were long before the term “cultural appropriation” existed, but Elvis—and many other white musicians before and after him—made their name and a ton of money on the talents of Black musicians who couldn’t even get airtime.

The Righteous Brothers were literally referred to as “blue-eyed soul” (allmusic.com). Bill Medley, the remaining “brother,” commented that they sang “Black music” and were grateful for Black music stations bringing them to prominence, calling it “a great honor.” When he went to replace his dead partner, however, the “only” person he could find was another white man.

Perhaps the group that has received the most—and the most conflicted—press for the influence of Black music is The Rolling Stones, named by Muddy Waters, no less. Guitarist Keith Richards said that Black music is “The reason I'm here.” Speaking to Rolling Stone magazine, he acknowledged the debt that the Stones owed to Blues and R&B artists, particularly Chuck Berry: “Nobody could write them like that, man. I mean, you want Rock & Roll? There it is.”

More controversially, however, this same man is quoted on loudersound.com as saying, “‘work songs’ and slavery have been around since the beginning of time”—and that the genre should not be defined by “race” and “I’m as Black as the ace of spades.” In another twist, the Stones supposedly helped promote numerous Black artists and have also paid for all of their funerals but have tried to keep it quiet.

It seems that white artists were aware of and thankful for the benefits they received from their Black counterparts, but were perhaps unwilling or unable to share the spotlight. Cultural appropriation was a thing long before it was a phrase. While white artists don’t deserve the credit some people give them for “popularizing” Black music, though, they have at least, by the mere fact of their own popularity, helped clear the way for a lot of today’s Black artists. It’s a convoluted and fascinating topic that in many ways surfaces the issues around racism in our broader culture; consider googling it for a deeper read.

The good news is that Black music dominates the charts today—whether Rap, Hip-Hop, or even the growing group of Black artists who perform Country music—and they’re finally earning their due. I’ve long realized that my Spotify playlist is almost 50/50 Black and white artists. I planned to include a personal “Top 10” for this article. Sadly, I was unable. There is just so much wonderful music out there, and how do you compare Thelonius Monk to, say, Leon Bridges or Macy Gray?!

I can say that Whitney Houston’s “I Will Always Love You” stops me absolutely dead in my tracks. Her depth and breadth, her clarity, her vocal and emotional range . . . it just blows me away Every. Single. Time. Repeat. Repeat.

Literally everything by Prince. After forty years of hearing some of his songs, I still sigh in the presence of his genius. Or H.E.R., singing “I Can’t Breathe”; if you can get through that one while still questioning why Black Lives Matter, you need to get your heart checked. And Tina Turner, the only person I’ve ever paid to see multiple times in person. Or . . . or . . . or . . .

So I made a Spotify playlist of my, you know, hundred or so favorites. Okay, maybe only fifty—I haven’t counted. I’ve been very arbitrary, so I know there are many holes. Point is, it’s fun to see other people’s favorites and debate them. Or add to them! Feel free to make suggestions in the Comments section. And whether you listen to mine or not, take a few minutes this last week of Black Music Appreciation Month to enjoy some of the most beautiful and heartbreaking music on planet earth.

Love one another.

Sherry Kappel

OHF Weekly Managing Editor

New This Week

Provincetown: Built by and for the LGBTQ Community

By Glenn Rocess

A week ago as of this writing (June 1), I’d never heard of Provincetown, Massachusetts (so much for my self-assumed Jeopardy-level knowledge of history and geography, right?). It turns out that, like most cisgender people, there’s a whole lot I don’t know about the LGBTQ community—not only its history or preferred destinations but also about the people themselves. Even for those of us who have close family members who are gay, love them, and happily accept them for who they are (as I do my brother-in-law and nephews), much of what we straight, cisgender people consider to be knowledge is often mainly assumption and conjecture.

My wife and I are given to spontaneity when it comes to traveling. On Wednesday of last week, we decided to fly to Boston for a few days, just to check things out, and fortunately, the nature of our work allows us to do so on short notice. The next day, we landed, got our bearings, and began to explore the city. Our first impressions were quite positive: it was cleaner than and as modern as Seattle.

As we walked along Boston’s waterfront, we discovered that there was a ferry to the tip of the Cape Cod peninsula. We were eager to check it out, if for no other reason than to traverse the waters the Kennedy family had sailed so often and to see what was so special about Cape Cod itself. So we bought tickets and boarded the passenger-only ferry at 9:00 on Saturday morning. We arrived at the Provincetown Marina about ninety minutes later, and as we walked down the long pier to the waterfront, it didn’t take long to see things were a little different here in what the locals call “P-Town.” Read the full story.

More from Our Writers

Pride and the “T” in LGBTQ

By Brian Mack

I walked throughout our local Target, searching high and low for this year’s Pride display. To my disappointment, I realized that I’d passed it on the way in. The bare, small display stood right by the little nook claimed by Starbucks. It had maybe four or five different shirts that I can only assume were unisex. I shouldn’t care much, considering that to countless companies Pride Month is just another political cash grab. However, it’s my wife and stepchildren’s first Pride as a family and I wanted something special to mark the occasion.

Pride Month is a celebration in memory of the Stonewall Riots of 1969 and in recognition of the humanity of LGBTQ people. It wasn’t always like that, and for me, it still takes a conscious effort to think of it that way. In 2020, more than one in three LGBTQ Americans faced discrimination. On any given day, one of us might be killed, beaten, raped, or put in countless dangerous situations simply because of who we are. Things like jobs, housing, and healthcare are harder for us to gain access to. Read the full story.

Giving

Please give. We cannot do the work of racial equity without the support of people like you. In the same way that it takes a village to raise a child, it will take all of us to end racism and create a more equitable world. Racism does just harm its victims; it harms its perpetrators and bystanders. Racism harms everyone.

Your tax-deductible donations will help us continue our anti-racism work. No donation is too small, be it one time or monthly. Thank you for your support.

Final Thoughts