I haven’t missed voting in an election in over forty-five years. Voting isn’t just a right; it’s a responsibility. One that my ancestors fought and died for. I voted when well off, when broke, sick and healthy, tired and rested. Before the pandemic, I almost always voted in person. I liked standing in line (short lines anyway), inserting the ballot, and getting the sticker saying I voted and wearing it all day at work.

Although I’m Black, I have never had a problem being able to vote. Voter suppression in modern times isn’t about stopping all minorities from voting. It’s about trimming voters from the herd, making it harder or impossible for some minorities, and convincing others that voting is futile and meaningless. I have been fortunate enough to have lived in precincts where voting hasn’t been discouraged. They didn’t move the polling places to inconvenient locations, the lines weren’t long, I had jobs where I could vote any time of day without penalty. But I’m reminded I live less than ten miles from Ocoee, Florida, which is in Orange County along with Orlando, where I live. Voting was once a life and death proposition there for Black people. It has been that way during much of America’s history. Let’s revisit some of that history lest we forget what it took to get where we are and why we’re still fighting for the right to vote.

A Brief History

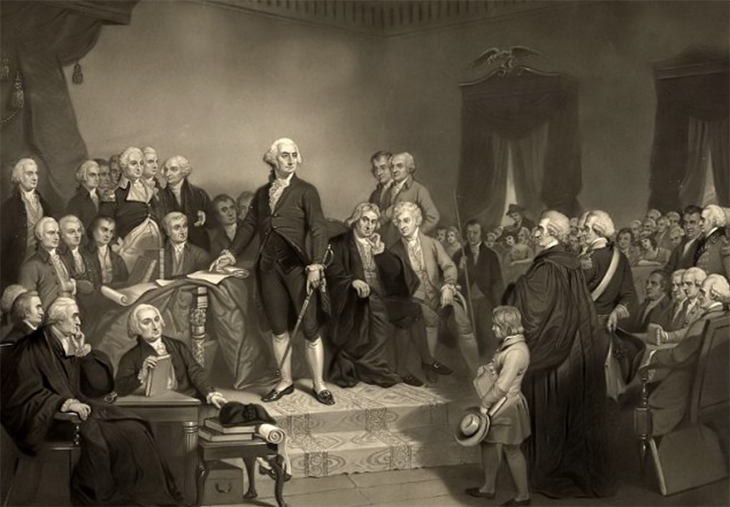

America’s first presidential election was held on January 7, 1789. The Electoral College had been put in place via the Constitution as a safeguard against the people making decisions the politicians disagreed with. The key issue was the enslavement of Black people, which the South wanted to continue indefinitely, and many in the North benefited. The Electoral College gave the less populated southern states more voting strength, especially when combined with the Constitution’s three-fifths clause. Article 1, Section 2, Clause 3 gave white Southerners additional voting strength by allowing states to include three-fifths of their enslaved population, thus increasing their representation in Congress and insuring enslavement could not be voted out.

When Americans give credit to the Founders as being all-wise and prescient, remember, the only ones allowed to vote were white men who owned land. This is who the system was set up to reward, and while much has changed, much has stayed the same.

Eighty-one years later in Salt Lake City, Utah, which was then a territory, the first woman cast a vote. Utah passed a law two days earlier giving women the right to vote. Seraph Young Ford, a grandniece of Mormon leader Brigham Young, was the first of about twenty-five women to vote that day. Ford eventually moved to Baltimore, Maryland, and when she died, was buried in Arlington Cemetery.

As you might have suspected, giving women the right to vote in Utah wasn’t simply related to women’s suffrage or equal rights. Two sides hoped to control the women’s vote after the passage of the 15th Amendment which gave Black men the right to vote (theoretically). Congress turned its focus to eliminating polygamy, the practice of allowing men to have more than one living wife, which some saw as another form of slavery. Many hoped that women would vote to end the practice. The Church of Latter-Day Saints or Mormons hoped to use women to defend the practice. The Mormon women generally did as their church (or husbands) asked and didn’t end the practice of polygamy. Congress, being Congress, ended the right of women to vote in 1887 because women weren’t voting the way they wanted.

Ramifications of the 15th Amendment

While a woman technically voted first on February 14, 1870, Black men received the right to vote with the Fifteenth Amendment, and Thomas Mundy Peterson cast the first Black vote on March 31, 1870, in Perth Amboy, New Jersey. Peterson was a janitor and active in both the Republican Party and Prohibition Party. He was also the first Black man in town to serve on a jury. The Fifteenth Amendment that allowed Peterson to vote was never undone. Still, various voter suppression methods arose to keep Black people in particular and minorities in general from maximizing their voting strength.

The immediate impact of the Fifteenth Amendment took place in the South. The Black population was much larger than the white one in many areas, and Black people started electing politicians. There were many forces marshaled against them. Cities, states, and counties passed the Black Codes after the war, which reinstituted slavery as best they could. These included many special laws for Black people, including curfews and vagrancy laws that if broken landed you in jail. Then you might be sentenced to the same plantation you were once freed from.

When Black people started getting elected, that was unacceptable, so Democratic party-led voter suppression kicked in. These included literacy tests, providing incorrect information about voting times and locations (kind of like modern-day robocalls), and, if those didn’t work, making an example of some would-be voters by beating or lynching them. According to one report in the Smithsonian, over 6,500 Black people were lynched during Reconstruction, the supposed Golden Age for Black Americans. Yeah, that could tend to discourage voting.

The only thing that somewhat protected the rights of Black voters in the South was the presence of federal troops who remained after the war to protect the newly freed. Black people started electing Black men to state legislatures and Congress. When Hiram Revels, a newly-elected Representative from Mississippi, attempted to take his seat in Congress, Democrats tried to block him.

After the contested presidential election of 1876, Republicans and Democrats conspired to let Republicans have the presidency and remove the federal troops from the South.

They argued the 1857 Dred Scott decision ruled that Black people weren’t citizens and had no rights the court was bound to recognize. Some Democrats said that Hiram Revels had not been a citizen of the United States for the nine years required by the Constitution and was thus ineligible. They maintained he became a citizen with the 1866 Civil Rights Act and thus had only been a citizen for four years. Revels and his counterparts from the 1870 election were later seated but definitely unwelcome.

I probably should have mentioned earlier that the end of the Civil War inspired the founding of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). They were a major force behind the threats against and murders of Black people trying to vote. In 1871, Congress did then what they are unwilling/unable to do now by enacting the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871, which was used for crushing the Klan, though Redshirts and White Leagues replaced them, along with White Councils (the Chamber of Commerce approved versions of the Klan).

Federal troops still kept most of the violence at bay though seven Black legislators were killed during Reconstruction and many others threatened or injured. After the contested presidential election of 1876, Republicans and Democrats conspired to let Republicans have the presidency and remove the federal troops from the South. Republican President Rutherford B. Hayes became President as a result of the Compromise of 1877. The next year he implemented Posse Comitatus, which ensured those troops would never return.

The removal of troops meant things could immediately go back to the way they were before. The modern-day equivalent would be in 2013 when the Supreme Court gutted the enforcement and preclearance provisions of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Those provisions required states and some municipalities to get permission first before enacting unconstitutional measures. The very next day, several states started enacting voter suppression bills, some of which have been found unconstitutional. Many are still winding their way through the court system. The 2013 Supreme Court decision paved the way for many of the forty-seven states currently trying to suppress minority and youth voters through laws that previously would have required the permission of the Supreme Court.

The impact of removing those troops in 1877 was the beginning of the Jim Crow era that would last until the mid-1960s.

Women’s Suffrage . . . vs the Black Male Vote

While women who sought the right to vote universally were on a different path than Black people with the same goal, the paths of both often intersected. There were two prominent women’s groups: the National Woman Suffrage Association, formed in 1869, and the American Woman Suffrage Association, founded the same year. Some of them saw their chance during the battle over the Fifteenth Amendment and insisted on an Amendment giving women the right to vote as well as Black men. Some aligned themselves with racist Southern groups in trying to block the Fifteenth Amendment. To their thinking, if women couldn’t get their rights, neither could Black men. By this time in America, even the poorest white man could vote, but women and Black people could not. Eventually, the Fifteenth Amendment passed, and in 1890 the two women’s groups reconciled.

White women weren’t the only ones interested in women getting the vote. Ida B. Wells, perhaps best known for her activism against lynching, began forming women’s clubs, including the Alpha Suffrage Club, to further voting rights for all women and teach Black women how to engage in politics. The leaders of the white groups wanted the support of Ida B. Wells and her organization but wanted nothing to do with her anti-lynching cause. The purported defense of the honor of white women was a factor in many lynchings, and Wells kept saying so. They wanted Wells’s support until they no longer needed it; the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified in 1920, giving women the right to vote. Once ratified, white groups distanced themselves from Wells, leaving her and her anti-lynching efforts to fend for themselves.

Women voted in their first presidential election in 1920. Apparently, for white men in the South, the prospect of Black men and all women voting at the same time was too much to bear. They had to live with white women, so they redoubled their efforts to stop the Black vote.

Ocoee: A Deadly Example of Voter Suppression

In Florida, where I live, there was a statewide conspiracy to keep Black people away from the polls. Not just the nibbling around the edges ways of today but the by-all-means-necessary approach. The effort was coordinated and involved Governor Sidney Johnston Catts, who refused to speak out against the frequent lynching of Black citizens in Florida. After leaving office, Catts was indicted for forcing two Black men to provide involuntary service (slavery) on his plantation. He was later found innocent by an all-white jury.

“Your Race is always harping on the disgrace it brings to the state by a concourse of white people taking revenge for the dishonoring of a white woman, when if you would . . . . teach your people not to kill our white officers and disgrace our white women, you would keep down a thousand times greater disgrace.” —Governor Sidney Johnston Catts

The Governor, state officials, local law enforcement, and the revitalized KKK that included many of the above planned to keep Black people from voting. In direct opposition to their efforts were Republicans attempting to organize Black voters to come to the polls in Ocoee, Florida, less than ten miles from my home.

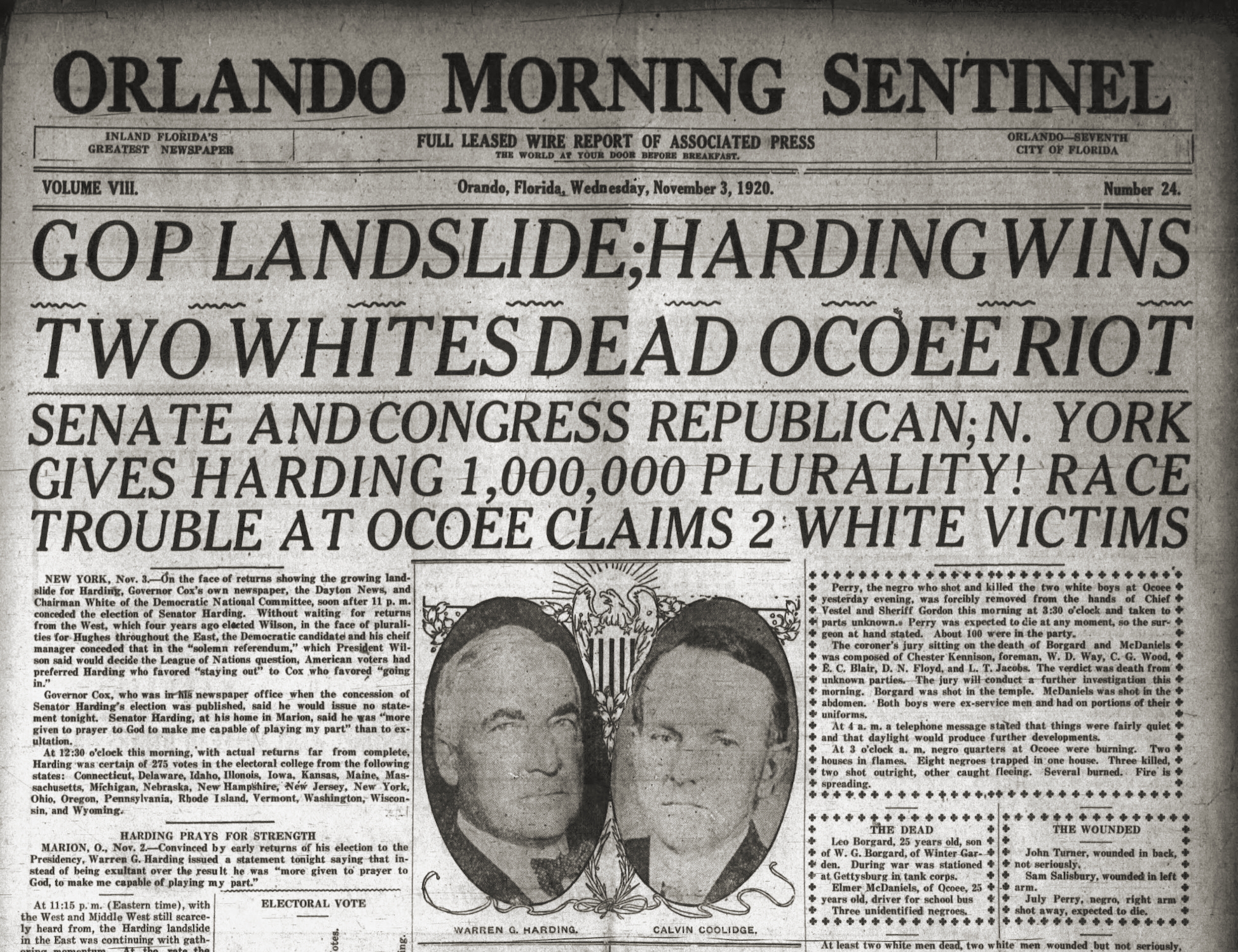

Moses Norman went to the polls on November 2, 1920, to cast his vote. He was turned away by white poll workers who said he hadn’t paid his $2 poll tax. He later returned to a car and was turned away again; it was “reported” he had a gun in the car. A white mob formed, led by a former City of Orlando police chief and future two-term Ocoee mayor, Samuel T. Salisbury. The mob went to the home of Norman’s friend July Perry to look for Norman. They tried forcing themselves into Perry’s home and were met by Black people standing their ground. A gunshot wounded Salisbury to his arm, and two white men were killed while attacking the Perry home.

July Perry was wounded and tried to escape while the posse regrouped, calling for reinforcements from nearby Winter Garden and Orlando. Perry was caught in a sugar cane patch and taken to a downtown Orlando jail. A new mob removed Perry from custody, brutalized and lynched him, hanging his body near the home of the white Judge John M. Cheney, who had been advising Norman and Perry about voting in Ocoee. Cheney had been warned two months earlier about the “consequences” of interfering with white supremacy. Norman escaped and was believed to have moved to New York City.

One might think after July Perry’s lynching, that would be the end of the matter. The Orlando Morning Sentinel headline featured in all caps, “TWO WHITES DEAD OCOEE RIOT.” The newspaper also ran ads encouraging World War I veterans to come to Ocoee to ensure “no more violence.” The violence didn’t end until the Black population in Ocoee were no more. An unknown number of Black people were killed; the official estimate was thirty-five to fifty but the likely number was in the hundreds. The rest were burned out, forced to leave their land and most of their belongings. Some of the Black residents were able to sell their land at a deeply discounted price. Others got nothing at all. A new ad began running in the Orlando Morning Sentinel, placed by the former Confederate soldier charged with redistributing the land.

“SPECIAL BARGAINS: Several beautiful little groves belonging to the Negroes that just left Ocoee. Must be sold — See B.M. Sims, Ocoee.”

Former Captain Bluford Sims had an orange grove that included most of downtown Ocoee and July Perry’s land. Black people lost an estimated nine million dollars in property after the Ocoee Massacre because a man tried to vote.

The New Jim Crow

Over a hundred years later, many things changed while others stayed the same. Jim Crow was finally eliminated on paper with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Federal Housing Act of 1968. As has always been true, new laws have popped up to accomplish the same thing. Current mass incarceration looks like the mass arrests of Black people during the Black Codes. Stop and Frisk practices in minority communities has mostly ended, but the over-policing of them has not. Poll taxes that were declared unconstitutional in the 24th Amendment have found their way into the Voter ID laws.

Florida voters expressed their will by passing a Constitutional Amendment restoring the right of non-violent felons to vote. The Florida legislature and governor nullified the voters by denying that right to felons who still owed fines to the state. Yet Florida can neither tell ex-felons if they owe money or how much.

Florida is but a microcosm of the voting story in America. What is true in the South is also true in the North. In addition to the thirteen states where the 1965 Voting Rights Act required preclearance for changing in voting policies, many municipalities also face that requirement based on their history. They included decidedly non-Southern locations like Bronx County, New York, and jurisdictions in South Dakota, Alaska, and Michigan. What the Supreme Court got right in their 2013 decision is that it wasn’t fair to single out Southern states for preclearance. Based on what’s happening in forty-seven states, the whole country needs to ask first before enacting racist laws.

America could and should do better about voting rights. We started by allowing only rich white men, eventually allowing most other adults while making some in particular fight each step of the way. Any of us could write a fair law, but Congress has no present will to enact one. Our current selection process leads to Supreme Court Justices who would later find it unconstitutional. I blame the entitlement and influence of rich white men who never truly ceded control in the first place. The remaining question is whether Americans will come together to impose their collective will and make a change. The jury is out on that one, but hope remains eternal.