“If a race has no history, it has no worthwhile tradition, it becomes a negligible factor in the thought of the world, and it stands in danger of being exterminated.”

—Dr. Carter G. Woodson,

Historian and inventor of what has become Black History Month

If there’s one thing the people of this country hold sacrosanct, it’s commemorating the sacrifice and service of our fallen military. Be it the site where American servicemen and women laid down their lives or the memorials erected to honor them, these grounds are set apart and designated holy. Who doesn’t tear up in the solitude of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C.? Millions pilgrimage to the Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial in northern France and are caught up in the solemnity of perfectly aligned crosses spread out over rolling fields bordered by windswept trees. (These are the same grounds featured in Stephen Spielberg’s epic, Saving Private Ryan.) What about the Pearl Harbor National Memorial in Hawai’i, where the Japanese sank the USS Oklahoma, and 429 souls perished? Or the granddaddy of them all, Arlington National Cemetery, the final resting place for over 14,000 veterans, dubbed our nation’s most hallowed ground.

It is impossible to visit these or other memorials and not be deeply moved to consider the lives of the deceased and the import of those lives upon a society as well as its legacy. Cemeteries and memorials record heroic events of the past. They tell of specific moments and the people who lived and died during that time. Inarguably, it’s the history of who we are.

Until it’s forgotten.

January 2020. Groveland, Florida, a small rural town about thirty miles due west on State Road 50 of Orlando and its attractions, announced Kevin Carroll as the new fire chief to replace the retiring fire chief of forty-five years. Chief Carroll had been with the neighboring Hernando County fire service for twenty-six years and served as deputy fire chief. The affable Carroll seemed an unusual choice given Groveland’s longstanding reputation of unassuming hamlet by day and sundown town by night.

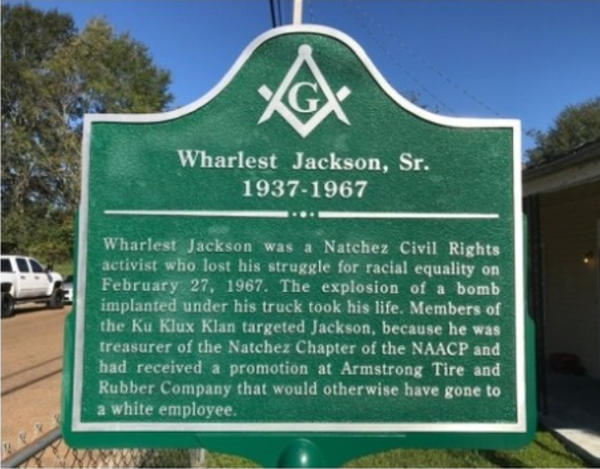

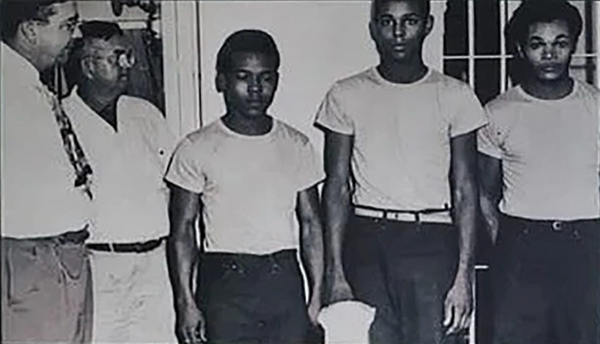

In its glory days, the town was known for its turpentine distillery, lumber production, and where, in 1950, a white woman falsely accused four Black men—Mr. Charles L. Greenlee, Mr. Walter Irvin, Mr. Samuel Shepherd, and Mr. Ernest Thomas—collectively referred to as the Groveland Four, of rape. Mr. Thomas was murdered while trying to evade capture. The remaining three were arrested, charged, tried, and convicted by all-white juries, despite no evidence the alleged attack took place.

The second trial is especially noteworthy as a young Thurgood Marshall, who would later become the nation’s first Black Supreme Court Justice, served as defense counsel for the remaining three men. Despite the U.S. Supreme Court overturning the convictions and ordering a fair retrial, another all-white jury handed down a second conviction. Irvin was shot and killed purportedly while trying to escape. Numerous incidents of racial terror against Black people garnered Groveland and its environs as openly hostile to Black people. Ultimately, Greenlee and Irvin were paroled and died with their respective families. In 2016, the city of Groveland and Lake County apologized to the descendants of the Groveland Four. And in 2019, the state of Florida posthumously pardoned them.

Chief Carroll, originally from Queens, New York, and of Irish descent, moved to Hernando County in 1977 at six years of age with his mother. One of his earliest memories in the sunshine state occurred during a routine trip to downtown Spring Hill in which his panic-stricken mother frantically warned the young Carroll to Get down! Stay down, and don’t look at them! Carroll, utterly bewildered, did as he was told and heard the approaching clip-clop of horseshoes parading down the middle of Spring Hill Drive.

As the hubbub subsided, Carroll stole a glance at the men in white robes and pointed white hats riding on horseback. Later, his mother explained the men were with the Ku Klux Klan. She emphatically told him he was to have nothing to do with them as they hated Black people, Jews, and Catholics—the faith the Carrolls practiced. Kevin wondered what kind of place his family had moved to. Spring Hill became a sharp contrast to his old neighborhood in Queens, where people of all ethnicities and faiths intermingled openly, and how his parents and family instilled in him to treat people equally and to always do the right thing.

Carroll never forgot the parade.

September 2021. The Groveland city manager emailed employees in search of volunteers to work on yet another attempt to refurbish the town’s old cemetery. Over the years, the city council members and several residents had unsuccessfully attempted to renovate the neglected “colored” cemetery. Due to the scope of the project and insufficient funding, prior attempts only brought about short-term results. Chief Carroll, an avid fan of history and experienced practitioner of community service, signed up within minutes to head the latest effort, with Mr. Deo Persaud, Groveland Human Resources Manager as his right-hand man.

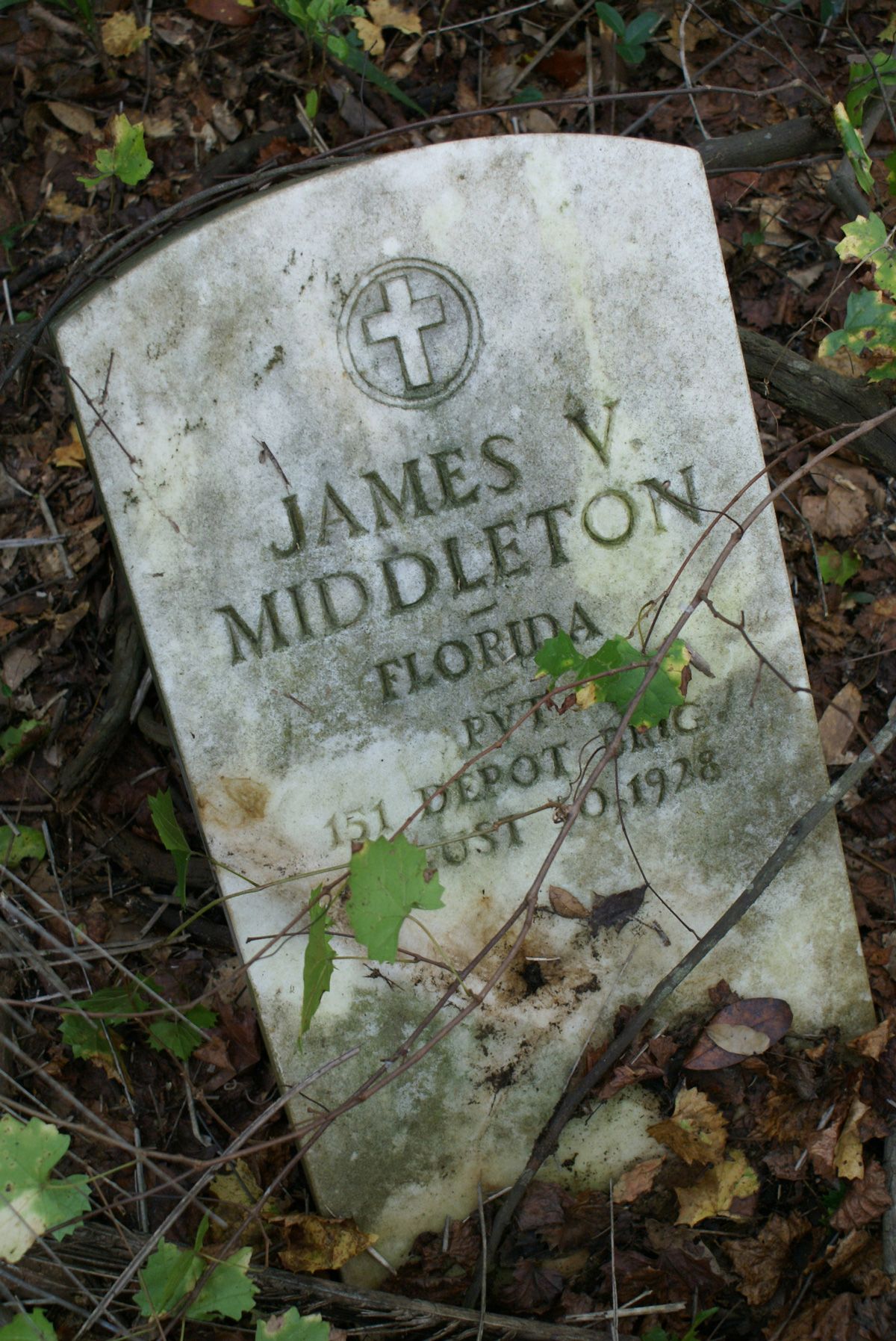

On their first trip, Carroll met a disheartening sight: a desecrated and long-forgotten graveyard, a little over an acre in size, walled in by houses on three sides and a church on the fourth, and thick with decades of unattended foliage growing wild. According to the Chief, it looked like the Amazon. Once inside, evidence of repeated acts of vandalism over the years was apparent. Massive, well-crafted headstones, some weighing well over a hundred pounds, had been knocked over and broken, with pieces strewn all over the ground. In one spot, a giant earpod (or elephant ear) tree, invasive in Florida, had grown with a grave marker embedded in its trunk. Some headstones identified World War I veterans. The project took on a sense of urgency.

Carroll and Persaud called on the community, first responders, former military personnel, and any and every person who’d listen—from anthropologists and archaeologists at nearby universities to the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs in Washington, D.C., and just about everywhere in between—to help determine the cemetery’s historic authenticity. The most help came from two sources close to home: 1) Groveland residents who had previously worked on the project, and volunteers from surrounding areas who learned of the latest attempt on the news. Both groups supplied death certificates that identified who was interred and when—between 1920 and 1950, and 2) a nearby imaging company that donated drones and LiDAR (light detection and ranging) imaging technology that revealed where the deceased had been buried.

As death certificates poured in, LiDAR imaging data, preliminary GPR (ground penetrating radar) data, and the final GPR data revealed where the deceased had been buried. This ground penetrating radar was the same technology used to map the location of several hundred bodies in Clearwater and Tampa, Florida, which the cities promised to move to make way for a parking lot, a school, and other facilities, but instead left deceased where they were only to be paved over. This wave of technical data boosted the estimated number of bodies interred from 70 to 229. Plus, according to archaeologists, potentially, there could be an additional twenty percent—an increase of 46 more people—who had not been buried in pine boxes.

Black residents, native Grovelanders, were intimately familiar with their forebears’ oral history of the town that had been passed down to them. These eyewitness accounts provided clues that would be corroborated by seemingly disparate facts and documents that, in all likelihood, would have been lost forever if not retrieved at that time time. Such was the case in determining the cemetery’s name and locating its rightful owner. In a conversation with Chief Carroll, Linda Charlton, a longtime Groveland resident, revealed that the cemetery had been called the “colored cemetery” by locals for as long as she could remember.

To better understand the cemetery’s importance, we have to examine how it came to be.

The Groveland of today was originally named Taylorville, after brothers C. C. and B. M. Taylor who started their turpentine distillery business on the land that would become Groveland. The Taylors chose the location because they essentially had no choice; the surrounding towns wouldn’t allow them to build their distillery and employ Black laborers within their borders because of . . . take a guess . . . their hatred of Black people, also known as racism.

Between 1895 and 1900, Elliott Erastus Edge moved to Taylorville, bought out the Taylor brothers, and brought Black families to town to work in the turpentine distillery, lumber mill, and citrus industries. The work of Black citizens in Taylorville put the industries on the map and was a boon to the city’s economy. With citrus, the economic impact was so great the town was dubbed “Groveland” because of the sprawling citrus groves in the area.

Between 1895 and 1900, Edge purchased and donated a 1.25-acre of land for the Oak Hill Union Colored Church of Taylorville’s graveyard. He did this because he’d brought a sizable number of Black people to town to work and live in Taylorville, and they needed a place to bury their loved ones. While it was a ways from the town’s only Black church, it was only natural for people to associate the town’s only Black cemetery with the town’s only Black church, Oak Hill Church. Charlton also spoke of the cemetery’s “big oak tree,” which explained why people started calling the burial ground the Oak Tree Union Colored Cemetery of Taylorville.

One problem: there was no oak tree visible.

The death certificates offered up other details about the people buried in the cemetery. Some were World War I veterans, others were members of the Order of the Knights of Pythias, the first fraternal order to be chartered by an act of Congress, a few were members of the International Order of Odd Fellows, some were clergy, and sadly there were even children.

While studying the growing number of death certificates, something unusual caught Carroll’s attention: a pattern of entries in one particular field on the death certificates proved troubling: Principal Cause of Death—

- Burned up in a house fire while intoxicated.

- Accidentally crushed to death by a fallen log.

- Injury to head and face by a piece of lumber.

- Beat to death with an axe handle.

- And multiple drownings.

To Carroll, these causes of death seemed suspicious. Were they plausible? Sure, but considering their number, the period in which these deaths occurred, and the well-documented racist sentiment of the time, it seemed highly unlikely that all those deaths of Black men in their late teens and early twenties were “accidental.” The bald-faced racism Black residents of Groveland endured because of the color of their skin awakened Chief Carroll many a night. But he channeled those emotions into a commitment to help the community restore dignity and honor to those who died and their descendants.

April 2022. Eight months after signing on to head the project, Chief Carroll and Mr. Persaud presented a proposal to the Florida Department of State for a $499,000 African-American Cultural and Historical Grant to finance the cemetery’s restoration. Despite being one of if not the oldest projects vying for funds, the state denied Groveland’s application. But two months later, the Fire Chief and Mr. Persaud were notified that the city’s application had been approved thanks to additional money allocated by the State of Florida.

September 2022. A year after Chief Carroll and Mr. Persaud answered the call to restore the old Groveland cemetery, a multiracial, multigenerational, cross-cultural alliance of residents reflective of the current Groveland, including archaeologists, anthropologists, first responders, and former military personnel, began clearing away seventy years of overgrowth and hate. For four months, eight hours every Friday, a rotation of people removed thirty-five truckloads of trees, weeds, and refuse. In return, the burial grounds surrendered headstones, some whole, shattered, some still presumably sunken into the ground below the surface, an undetermined number missing due to vandalism and theft . . . and to everyone’s astonishment, the petrified remains of an enormous white oak tree.

Plans for the cemetery include . . . an informational kiosk, a pavilion with markers listing those interred, an area paying homage to interred veterans, an area to honor the children interred, and more. And only hours ago, Chief Carroll informed me that the state approved granite markers for each person interred. Currently, part of the grant’s terms stipulate the project must be completed by June 2023. That’s not going to happen, but Chief Carroll can and will apply for a six-month extension on Groveland’s behalf.

“A people without knowledge of their past history, origin, and culture is like a tree without roots.”

—Marcus Garvey

Of late, there’s been a concerted effort to silence any discussion of Black history or even acknowledge Black people’s contributions to the American adventure. The trend now is to erase those accomplishments en masse from this country’s collective memory. This is nothing new, but yet another high tide of this nation’s ebb and flow dalliance with white supremacy. Dr. Henry Louis Gates in his book The Stony Road refers to the period after Reconstruction as the former Confederacy’s “Redemption,” “when the gains of Reconstruction were systematically erased and the country witnessed the rise of a white supremacist ideology that, we might say, went rogue.”

This current era—following the Civil Rights era, with its hallmark legislation that ushered in unparalleled social, economic, and political advances for Black Americans, and culminated with the election of Barack Obama, America’s first Black president—can be viewed as another “Redemption” for white supremacy, marked by methodical rollbacks of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

It’s history. Now.

Past events, if left unexamined will catapult us down the same predictable road to ignorance, fear, and loathing that will in every case and instance rob us of a brighter future that is well within this country’s grasp, kill our potential to become the best versions of our united Black, white, and citizenry of radiant color, and destroy the promise of freedom and equality as set forth in our Constitution.

Eschewing the facts of America’s past doesn’t return the powerful to a former glory. It willfully turns back the hands of time to a distorted fun-house mirror depiction of an Age of Ignorance. Only deep and truthful analyses of past actions—noble and dishonorable—can heal the wounds of both the victim and perpetrator. As Bishop Desmond Tutu wrote, “My humanity is bound up in yours, for we can only be human together.”

Our Human Family is founded on hopefulness and confidence about the future, grounded in visible acts of empathy. What’s taking place in Groveland is testament to the notion that people, even a community, can affect change when they bring their whole selves to a cause, treat one another with care and respect, and listen with the intention of learning and growing. Anyone who still doubts that change is possible, isn’t paying attention.

One need only speak with seventy-seven-year-old Groveland native Mr. Sam Griffin, who was born four years before the Groveland Four tragedy. He’s witnessed more injustice than most in his hometown. Mr. Griffin also has an uncle interred in the cemetery. From his vantage point, this project is healing the relationships between Blacks and whites in Taylorville. They are working side by side to restore history, and in so doing are creating a newer, healthier legacy. He holds no grudge against the people who’ve done his ancestors wrong and says this project inspires him to be a better person. “I’ve seen this cemetery tear down walls between people. I’ve seen it tear down my own silly thoughts about the division between Blacks and whites.”

Today, Groveland is one of the most ethnically diverse and fastest growing towns in Florida. New residents are attracted to Groveland’s low cost of living. The bedroom community boasts reasonable prices for first time homeowners, quality schools, and homey small-town charm. People are looking for space, they want to build a new sense of community. One that is open and accepting of everyone.

When asked about his motivation for working on the cemetery, Mr. Persaud responded, “It’s my role as a civil servant. It’s the right thing to do for the community. Our lives are all intertwined. It’s not just fixing things up and making them right. It’s about taking care of the people in the community; the people who served and sacrificed themselves on a higher level. They gave everything. As a city employee, you can’t help but ask yourself if you were in the shoes of the descendants, why haven’t they done better by us? I’m doing this because it’s the right thing to do.”

Chief Carroll wonders why he hadn’t heard about what happened in Groveland before he became involved with the project. “It’s disturbing how things went down. I can only imagine the fear those poor folks lived with everyday, especially considering they were the workers for the town’s industries.”

Some would have everyone believe that learning about Black history will divide people and make matters worse. Carroll has a different opinion. “This project has unified so many people in the community.” He says of their community meetings about the cemetery, “Everyone leaves their political affiliations at the door. The main purpose is to restore dignity, respect, and honor to the civilians and World War I veterans who were forgotten about in the cemetery. A person’s skin color should never play a part in stopping someone from doing the right thing. It shouldn’t play a part in anything. It’s kinda easy: do what’s right. Treat people like you want to be treated.”

To many in America, imaging this country’s past without acknowledging Europeans’ contributions would be impossible. Let’s apply the same standard be applied to the accomplishments of Black people, brought here enslaved and whose blood, sweat, and tears built this country.

Since learning of the Oak Tree Hill Union Colored Cemetery of Taylorville almost a month ago, this nonfiction story takes on significant meaning for me personally. I say that because in the middle of preparing this article, I learned from one of my cousins that we have relatives going back four generations buried in the segregated Black cemetery in Webster, Florida, minutes from Groveland. City officials are currently being challenged in their decision to sell the town’s Black cemetery to a developer.

Black cemeteries across the country are sacred.

Even after they’re valuable.

Love one another.

Member discussion