Zora Neale Hurston brought the Black experience alive. She wove stories that spoke to us in stark fashion about our history. Her last published novel, Barracoon: The Story of the Last Black Cargo, does exactly this. Although published ninety years after she wrote it, Barracoon is one of Ms. Hurston’s earliest works. Nothing prepares you for the story of Oluale Kossula — who was given the slave name of Cudjo Lewis. Cudjo was previously thought to be the last-known survivor of the slave ship the Clotilda. Later, another survivor, Redoshi (Sally Smith) was located and deemed the last survivor.

Ms. Hurston studied cultural anthropology before she decided to write novels. It is the reason she was so adept at writing dialogue, which reflected the time period of her characters. She strove to be historically accurate, and because of that, she faced criticism from contemporaries such as Richard Wright, author of Native Son, who claimed she perpetuated stereotypes about Black people by writing characters as if they were minstrels.

She didn’t let this criticism deter her. Instead, she continued to write prose that brought her characters to life in a way that informed us about their culture and history. This is one of the many reasons her novels are still discussed, critiqued and praised. Her words live on because she helps us understand our ancestors when they are no longer here to tell their own stories.

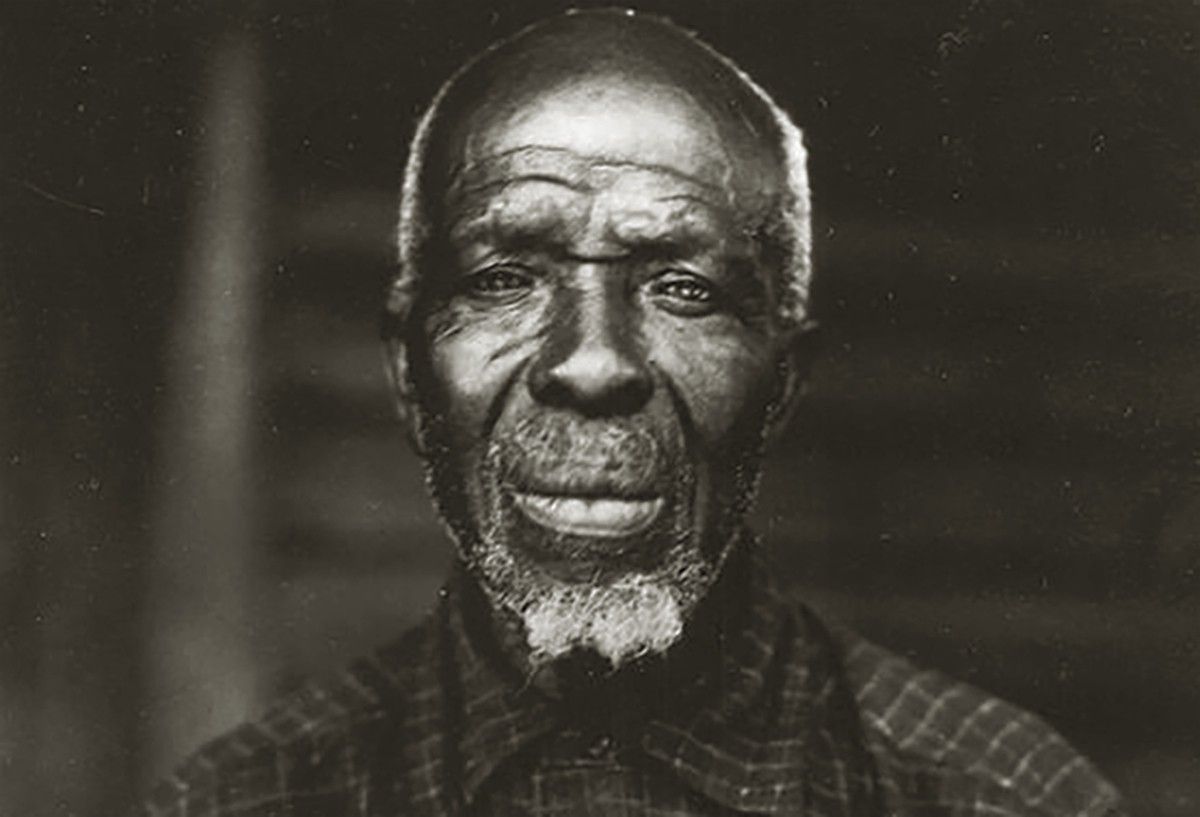

In Barracoon, Ms. Hurston conveys Cudjo’s words in his own dialect. She conducted a series of interviews with him, and what came out of these interviews was a heartbreaking story of a young man kidnapped from Africa who survived the Middle Passage and lived to see the enaction of the Emancipation Proclamation. His lined face tells us of the harsh life he survived. His words cut deep as his story unfolds.

Cudjo was born in what is now the country of Benin in West Africa. He was kidnapped at age nineteen by a neighboring tribe and sold into slavery. It wasn’t uncommon for Africans to sell other Africans to white slavers. His harrowing account of the Middle Passage is a grim tale of inhumanity and physical abuse. His terror and uncertainty are made even more horrific for the reader because, unlike Cudjo, we know what awaits him in America.

Reading his story in Barracoon gives us a rare, firsthand account of the Middle Passage. The stories we do know tell us of the brutality of this voyage. Cudjo himself speaks of wanting to die on more than one occasion during his passage on the Clotilda, the last slave ship to dock on U.S. soil. The sights, the smells, the tastes are described in explicit detail from the surviving stories of enslaved Africans who made the trip.

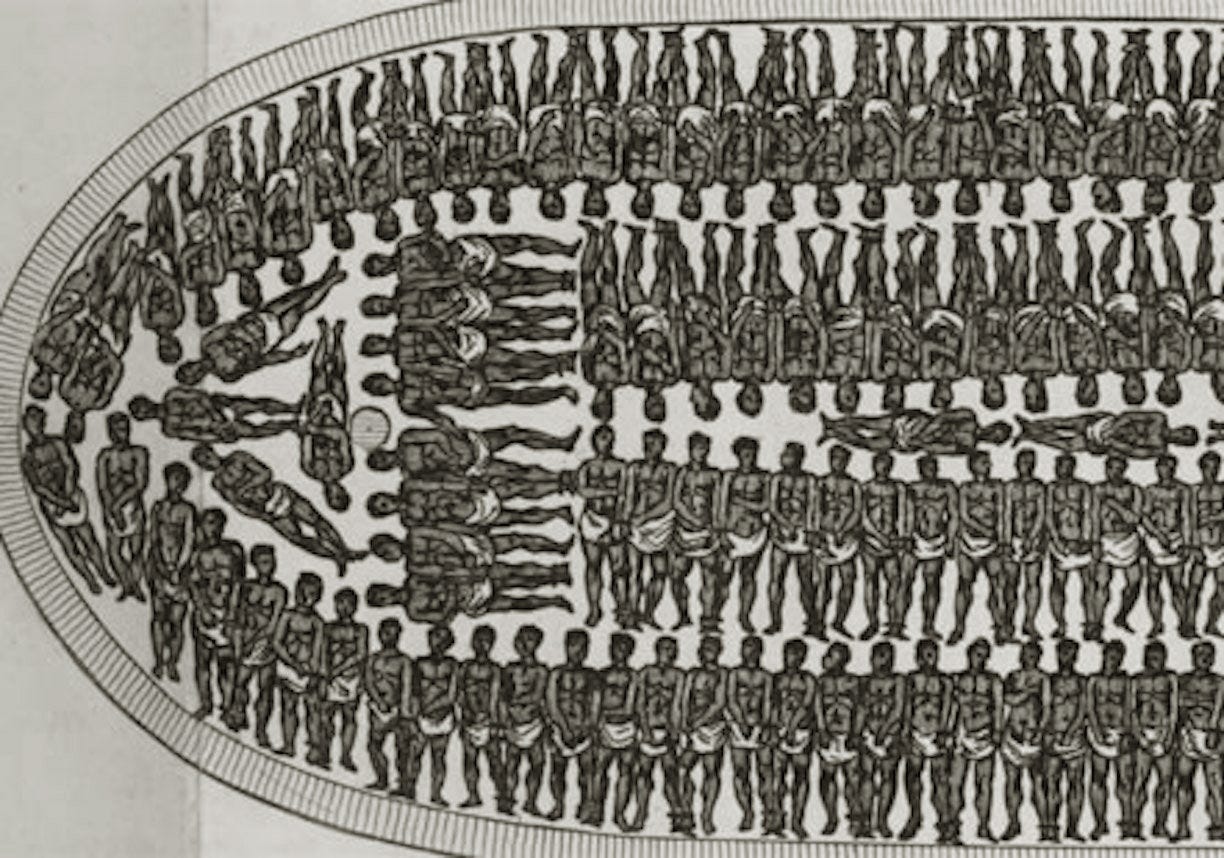

As I read Cudjo’s account, the illustration I have seen of Africans packed into a ship’s hold flashed through my mind. I remembered the other accounts of the Middle Passage I read. None of the Africans had been on such a ship before. Many became seasick during the voyage. They also were sick with worry, wondering about their families and the uncertainty of what lay ahead for them. Many died, and it wasn’t uncommon to be chained for days to someone who had died until a crew member came down to remove the body and unceremoniously toss it over the side.

The kidnapped Africans were given meager rations. Even if the captain lost some cargo, he could still make a profit when he sold the Africans at auction. Imagine day in and day out hearing the sounds of retching, the moans of agony, the cries of loneliness. Imagine enduring the smells of unwashed bodies, urine, and vomit permeating the small space with nowhere to go to breathe in fresh air. These voyages were not a matter of weeks but a matter of months. Cudjo’s voyage took seventy days. During this time, the stolen Africans were starved, beaten, and raped. There was no escape unless they jumped overboard or died by some other means.

Cudjo is the face we needed to complete the picture of these brutal voyages that brought our ancestors to this country. His story makes me think about my ancestors, whose journey is lost to me. I wonder if they endured the same thing. I wonder how many of my ancestors didn’t survive. I think about the strength it must have taken to fight to live. I wonder how the ones who knew they were dying felt when they realized they would never see their loved ones again. I wonder about the ones who did survive the journey and came to the same realization, that their families were lost to them.

Ms. Hurston shares this story so vividly, that we can picture a young Cudjo in our minds. We see a nineteen-year-old young African man chained and naked as he’s marched from his village to an awaiting ship. His terror of the unknown must have been unbearable. Although Cudjo came to America with no family, many slaves were kidnapped along with relatives, only to see them sold off and separated at auction. Cudjo mentioned he was kept in a barracoon (or barracks) until he was sold. He must have been there long enough to see the suffering of his fellow Africans. Perhaps that was the first time his eyes took in the overseer’s whips and the auctioneer chanting as white men competed for the strongest bucks and most fertile wenches. Cudjo doesn’t go into detail about what it was like to be bought, but it must have felt like a nightmare that would never end.

We know much about the lives of enslaved people on plantations. They worked sunup to sundown, and overseers were not lenient with their whips. Cudjo talks about the ever-present threat of whippings. So while there may not regularly have been physical violence, the threat of a beating was enough to keep them performing the backbreaking labor until they stumbled to their shacks each evening.

In Barracoon, Ms. Hurston told how she waited for Cudjo to convey his stories. She seemed to understand the pain that reliving these experiences caused him, so she relayed afternoons they spent eating watermelon under a tree outside of his shack or just sitting together listening to the silence. Ms. Hurston must have been astounded by what she heard as she listened to this man telling story after story of his life — a life that profoundly changed Ms. Hurston and influenced how she viewed the Black experience in her later writings.

The interviews captured in the book took place over a series of several meetings, and Cudjo seemed at times happy to see Ms. Hurston and other times resentful. While he wanted to tell his story, reliving it brought him pain. Cudjo was an old man by the time they started. In addition to recounting his Middle Passage and slavery, Cudjo told Ms. Hurston of happier times, in particular, his marriage to his wife in 1888 and the six children they produced.

Cudjo also gave an account of the deaths of his children and his wife. One son disappeared and was assumed killed. Another son was murdered by a police officer. His wife and the remaining four children died from illnesses. So just as he was alone when he boarded that slave ship, he was alone again in a tiny shack telling his story to a young woman who persistently, yet gently, nudged him to relive these tragic events. Cudjo’s life is one of so much loss, but it is also one of survival.

Cudjo died at age ninety-four. He held on to his story until someone came along who wanted to not only hear it but preserve it. It’s obvious that he and Ms. Hurston forged a strong bond during their meetings. Cudjo gave her a firsthand account of his life’s story, which not only forged a strong bond between them but also reverberated in her later writings. In return, Ms. Hurston gave him a sense of peace in knowing that his story — the story of an enslaved African becoming an emancipated American — would not be forgotten.

Top image: Cudjo Lewis (Erik Overbey Collection, The Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of South Alabama)