Editor’s Letter

In the past couple months I was near a couple of racist incidents involving Black women I know, and the incidents made me angry but also got me thinking about anger and how we deal with it.

The first was while shopping with Aisha, my Brazilian daughter, a former exchange student who’s now at Wellesley College on full scholarship but comes home to us for the breaks. She is very smart, as you might guess, with excellent English skills (she actually contributed an essay to Our Human Family’s Fieldnotes on Allyship when she was just seventeen!), and hopes to be a doctor someday. She’s also super kind, sweet, and bubbly.

Our whole family was shopping at a little boutique near my sister’s house in Illinois, each of us wandering around in different areas, and Aisha was bopping between us, looking at this and that. The store has a wide range of unique offerings, and I typically spend several hundred dollars there when we visit. I was already holding several shirts when my husband informed me that Aisha had left to sit outside and wait for us. It seemed a clerk was following her every step and glaring.

We have four Black Brazilian daughters we’ve gone various places with, and while I’ve seen hints of racism I hadn’t seen anything that overt. I think sometimes our white privilege extends to them, but in this case the woman saw her with us, referring to us as Mama and Dad, as she does, and it didn’t matter to the clerk.

We were furious. We dropped our potential purchases and walked out. Aisha, who has twenty-one years of experiencing racism, didn’t seem as upset as I was, but her sense was that the woman didn’t want her in the store.

We wrote a letter, and we won’t going be back.

The second incident was much scarier, although I wasn’t present. For some background, Earnest M. Lee was a Black folk art painter who grew up near Raleigh, North Carolina (where I live) and worked toward an art degree at St. Augustine’s University, an HBCU in town, until the grant program was pulled. He then moved to Florida where he died relatively young. His widow is friends with one of my besties and I also love folk art, so when she came to town to show his work at St. Augustine’s I had to check it out.

Choosing prints to purchase was difficult as Earnest had been very prolific, and many of them reflected sites in the Raleigh-Durham area, including families, farms, houses, forests, streams, and more. I narrowed my options down to a couple of prints and went up to pay, chatting with his wife Gloria, when I spotted a print that was unlike the others: a building and several Black folks engulfed in flames.

She said it was painted from an old article about the 1923 Black massacre in Rosewood, Florida. I assured her that I knew about Rosewood and asked her if she’d had any issues at showings around Florida. Just one, she said, her eyes turning dark and her voice trembling. Some men in one town told her “She’d better stop showing that painting” . . . and then that night, in 2023, someone burned a cross in the lawn of where she was staying!

The news is pocked with examples of racism, but I hadn’t heard of a cross burning any time recently—and I’ve never talked directly to a victim of something so heinous. It had obviously affected her deeply and she was still hurt and seething. What does one even say, besides “I’m so sorry”?

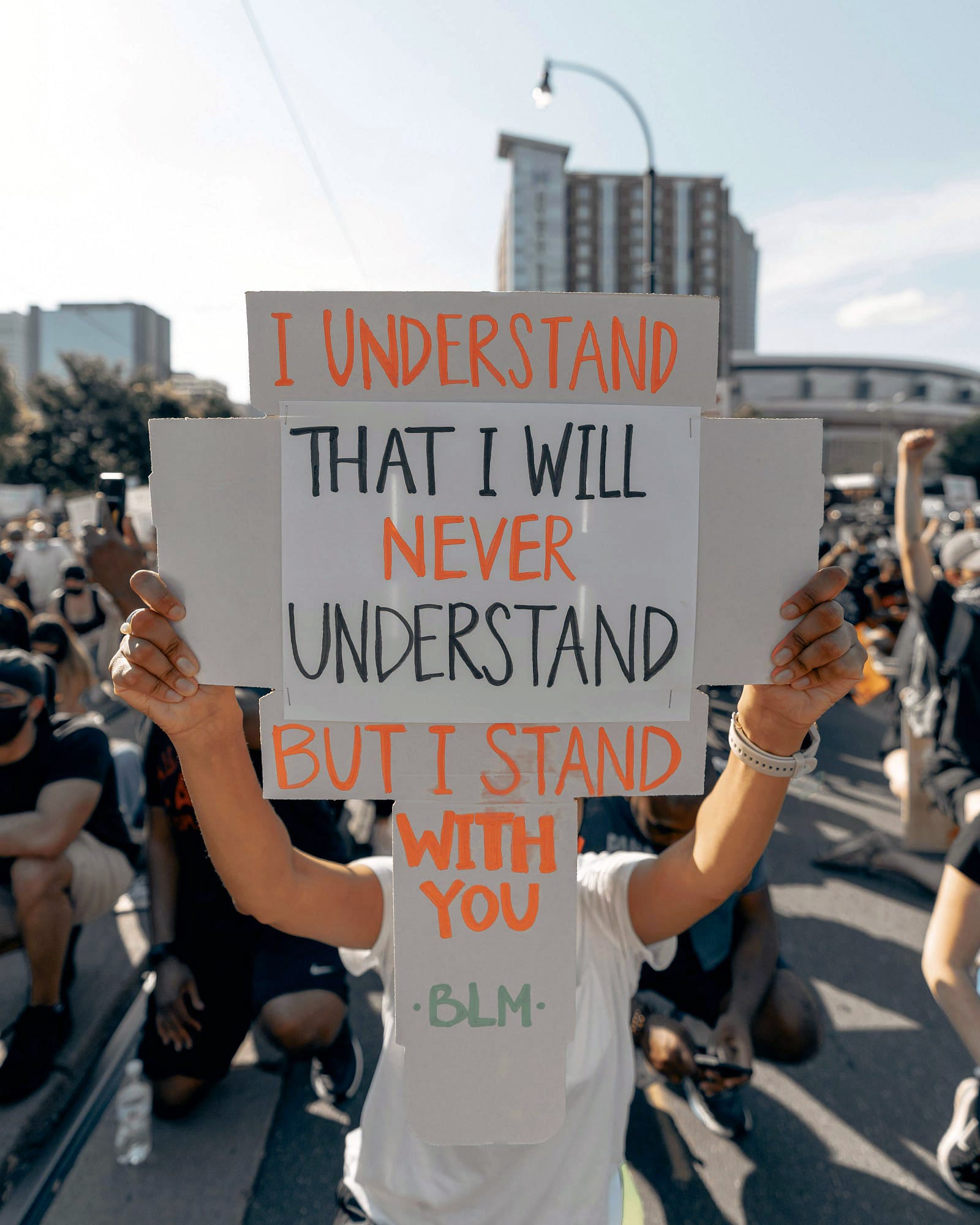

There’s always been a question of how, or if, even typically decent people understand empathy and others’ pain. Black people often ask why more white people can’t understand how they feel. We’ve all been angry! We’ve all felt pain!

If you’ve only read my essays here in OHF Weekly, you know I feel very strongly about human equity and equality. I will say that seeing racism directed at my daughter, and hearing from a victim like Gloria, really drove it home.

When I get angry, however, whether it’s about racism, misogyny, homophobia, or any other injustice, the response from many people has been, “I can’t listen when you talk that way.”

Why is that?

When a man gets mad, a white man, people stop and listen. The higher his perceived social standing, the more seriously we take his anger. He is passionate! He is earnest! He’s saying something important! Of course, men without the same social clout don’t get quite the same level of due, but particularly men of color. White people tend to have an unjustified fear of Black men in general, and when Black men are angry we tend to get scared. There are racist tropes about angry Black men–Black people, really–dating back to the first days of enslavement.

I know anyone who’s not a white man is typically considered much less influential when angry; I have observed this many times over the years, but studies such as this one from Harvard also confirm it. Black people’s anger is dismissed as “violent” or “uncivilized,” and irate women are considered “emotional” or “hormonal,” but the goal and the end result is the same—to dismiss the person and the reason they’re upset.

Think about the emotional constraints faced by Kamala Harris, Hillary Clinton, or Barack Obama when debating or campaigning. Think about how many Black men have been killed by police because the officers claim to have “feared for their lives.” Think about how feminists have been called “angry lesbians” for several decades. (And yes, the derogatory use of “lesbian” is a whole other level of misappropriated insult.) Think about the fact that there are so many Americans who are dismissive about what happened to Aisha, to Gloria, and to my response.

We all have the right to express our anger. We all deserve to be taken seriously when we are. And we all have the most basic right to express our feelings and perceptions—but then, that means others might have to acknowledge that the injustices that upset us have validity. Maybe Black people and women do have a right to equal pay . . . equal housing . . . bodily autonomy . . . not being followed in a store or facing a burning cross in the middle of the night.

Nobody knows this better than Black women, who are on the receiving end of the obvious double whammy that has arbitrarily placed them at the bottom of the social heap, making “angry Black women” such a common trope it almost sounds redundant. After racist incidents like the ones above, however, white people should all be angry for them instead of at them. Because make no mistake: the people committing those racist and sexist acts are often our friends, neighbors, and family.

Black women in my experience have been nicer and kinder than many people I know, despite the extra burden they carry. So let’s speak up when we hear people perpetuating well-worn tropes, and speak up even more loudly when we see racist incidents.

Sherry Kappel

OHF Weekly Managing Editor

IN HONOR OF BLACK HISTORY MONTH

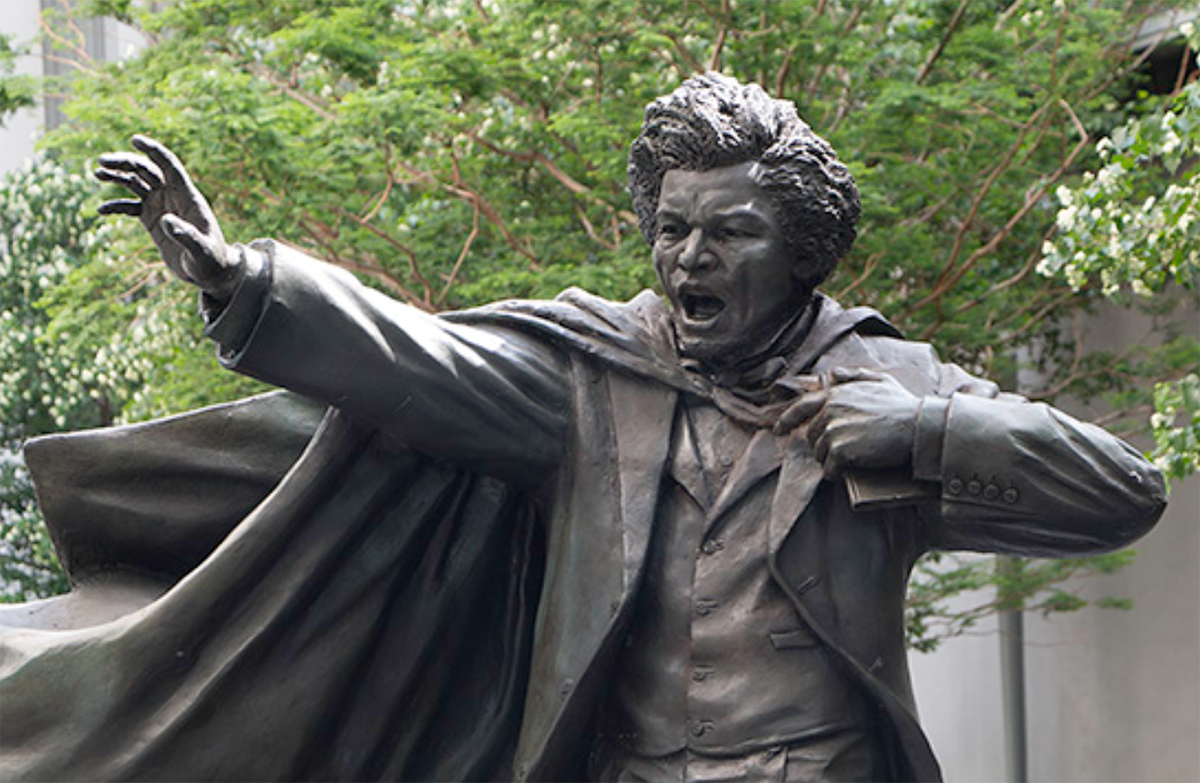

Frederick Douglass: An American in Ireland

(Part I)

This story began in the autumn of last year when I read these words on a poster: “2020 celebrates Ireland’s connection with Frederick Douglass on the 175th anniversary of the months he spent visiting the country.”

And I realised I had never heard of Frederick Douglass.

The organisation I volunteer for had decided to cooperate with Cork University to celebrate the 175th anniversary of Frederick Douglass’s visit to Cork in 1845. Together they organised a week-long celebration with a series of talks, lectures, and creative webinars on music and art to commemorate his visit, culminating with a powerful closing event on the 14th of February, his birthday.

I recall feeling ashamed at having to admit I had never heard of him.

All the more because on the backdrop of the killing of African American George Floyd in 2020, police brutality, and the rise of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement worldwide, I began researching the reasons for systemic racism in the USA. As I did not go further back than the Jim Crow Laws introduced after Douglass’s death, I did not include the cross-Atlantic trade of enslaved people and the ensuing global abolitionist movement, and thus failed to discover its famous representative, Frederick Douglass.

Read the full article at OHF Weekly.

Frederick Douglass: An American in Ireland

(Part II)

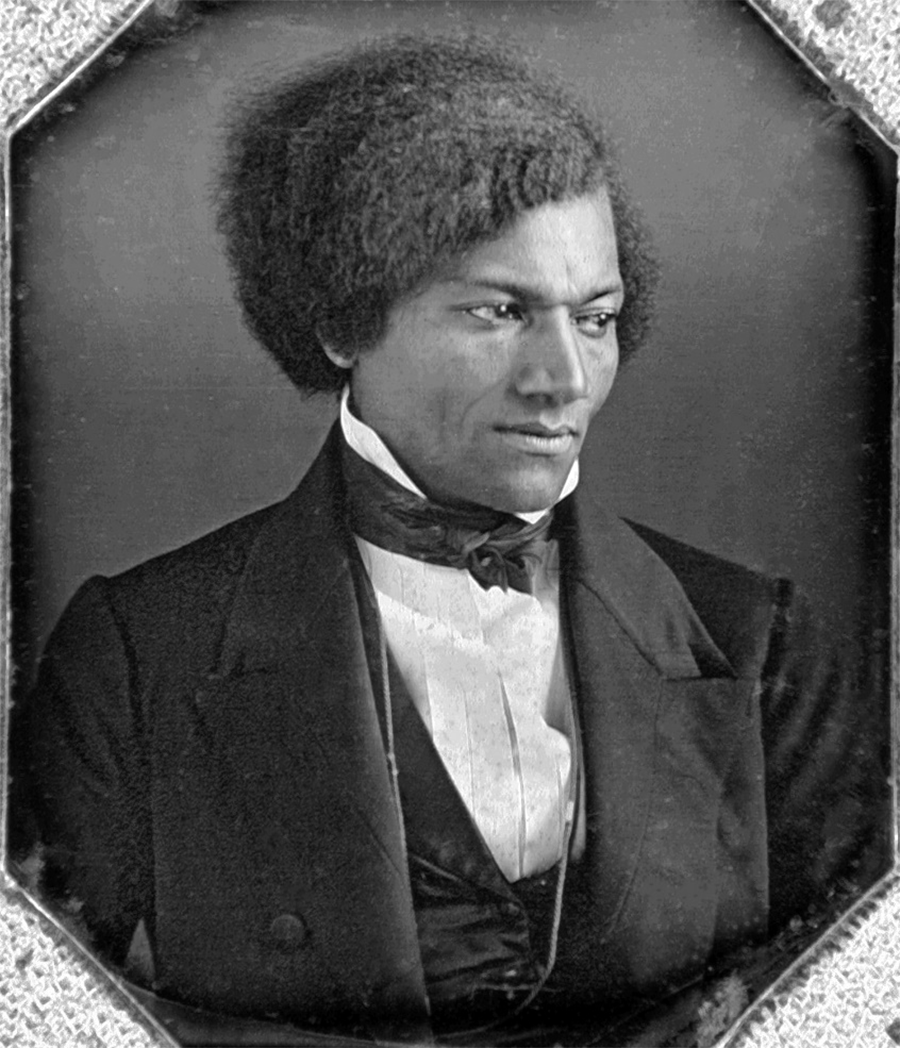

During his lifetime, Frederick Douglass lectured not only on anti-slavery but also on temperance, women’s rights, racism, and social justice for all; he edited and owned newspapers; advised presidents; and wrote three versions of his life story. It was the publication in 1845 of his first and most popular autobiography — Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave — that became a bestseller, especially in Europe. This levered him to international prominence and triggered his visit to Ireland in that same year.

Douglass wrote the Narrative to counter accusations that he was an impostor. How indeed could a young man, a formerly enslaved man, have learned the linguistic and rhetorical skills he used in his speeches on behalf of the American Anti-Slavery Society? To prove his authenticity, Douglass had to give details of names, dates, and places, information which put him at risk of being recaptured into enslavement. Though he had escaped to a so-called Free State, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 meant that Douglass was in constant danger of being captured, returned to his ‘master’ and punished. (Lee Jenkins. Beyond the Pale, p. 80–81)

Persuaded to travel to Britain and Ireland for his safety, and where, too, he could promote the work of the American Anti-Slavery Society, Douglass reluctantly agreed to leave his wife and four small children and went into self-exile between 1845 and 1847.

The idea, however, of visiting Ireland was not strange to him. He had long been an admirer of the Irish nationalist and vociferous abolitionist Danial O’Connell, famous for his flaming speeches on freedom, social justice and, unusual for politicians at the time, his strong stance against enslavement. Douglass’s wish was to meet him.

Read the full article at OHF Weekly.

Frederick Douglass: An American in Ireland

(Part III)

During his lifetime, Frederick Douglass lectured not only on anti-slavery but also on temperance, women’s rights, racism, and social justice for all; he edited and owned newspapers; advised presidents; and wrote three versions of his life story. It was the publication in 1845 of his first and most popular autobiography — Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave — that became a bestseller, especially in Europe. This levered him to international prominence and triggered his visit to Ireland in that same year.

To prove the authenticity of his words in the Narrative, Douglass gave details of personal information which put him at risk of being recaptured into enslavement. Though he was living in one of the so-called Free States, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 meant that Douglass remained in constant danger.

So, persuaded by his abolitionist friends, he opted for a period of exile in Ireland and Great Britain, which lasted almost two years. He first went to Ireland in August 1845 where he was warmly welcomed and, for the first time in his life, he experienced what it meant to be treated as equal.

Shared Brilliance, Champions of Human Rights, and a Universal Desire for Freedom

“I despise any government which, while it boasts of liberty, is guilty of slavery, the greatest crime that can be committed by humanity against humanity.” — Daniel O’Connell in 1845, the year of Douglass’s arrival in Ireland.

Read the full article at OHF Weekly

Anti-Racism 101: Own Your Racism

You’ve heard all the clapbacks.

“I have lots of Black friends!”

“My neighbours are Indian, they bring us over samosas all the time!”

“My brother is married to a Black man!”

And, of course, everyone’s favourite, “I don’t see colour!”

As if that proves the utter impossibility of their being racist. It’s laughable. It’s insulting. How dare you even suggest it?

People rarely react well when someone points out their racist behaviour. Point out sexist or homophobic behaviour, say, and they’ll try to laugh it off. But racism? We’re outraged. White people are incredibly touchy about being labelled racist. Most of us will declare we’re anti-racist and we’ve been misunderstood. But few of us are genuinely, actively anti-racist. Even fewer embrace anti-racism 101.

The True Foundation of Anti-racism

Approximately 99.9% of well-meaning white people like me approach anti-racism with the goal of being able to declare that we aren’t racist. We recognise that racism is a deeply rooted, centuries-old systemic injustice that has robbed millions of people of dignity, opportunity and life. We want no part in that, so we Do The Work.

Read the full article at OHF Weekly.

Let’s Talk Black Excellence, People!

The increasing hate and bigotry of the past several years has become almost unbearable in America. It’s as if almost half of our fellow Americans have traded in every shred of their integrity—nay, their very humanity—for the right to be openly racist . . . sexist . . . homophobic . . . transphobic . . . xenophobic . . . . If you’re in one of the oppressed groups, I can imagine the added fear and horror, and I’m so sorry. If you’re a straight white person but at all empathetic, and I suspect you are if you’re reading OHF Weekly, it’s heartbreaking.

It’s become so painful that my family has considered moving overseas, but that would be taking advantage of our privilege and so unfair to the groups being targeted, many of whom lack this flexibility. And sadly, where America goes, all too often other countries go, as well. My daughters in Brazil, Italy, Spain, and France (for those who are unaware, we’ve hosted almost a dozen exchange students over the years) have all reported a rise in fascism and bigotry in their countries.

Life has become a delicate balancing act of keeping up with the news so I can be as supportive as possible, while at the same time trying to keep it all to a low roar for my mental health. (I know I’m hardly alone in this, take care of yourselves!)

I lauded the beginning of Pride Month with some my gay and trans friends this past week by running a Love is Love 5K and enjoying our annual Pride Celebration / drag queen show, and for the first time I worried about our safety there . . . wondered whether I shouldn’t have taken two of my daughters (fortunately, it was happy as other years).

At the same time, I was horrified to hear about Ajike “AJ” Owens, a Black mother of four who was shot to death by a white woman through a closed door in front of her child. Worse, the local sheriff debated whether to press charges until it became national news (as is too often the case), and then charged the shooter with manslaughter! This was both murder and a hate crime, people: the killer spewed racist insults at AJ’s children, she knew AJ would be coming to discuss it, she had her gun waiting, and she never even opened the door!

A lot of people just shook their heads and said “Florida,” but let’s not kid ourselves: it could happen in a lot of the fifty states, including my own. And “Stand your ground” laws need to be recognized as the racist excuses for murder they are and removed from the books.

Read the full article at OHF Weekly.

Calling all Poets

As a reminder, Tapestry is a new section of Our Human Family devoted to poetry that celebrates both our similarities and our differences, but most of all our shared humanity — and our first few poems will be available this week! It’s poetry that seeks to recognize the contributions from . . . foster racial equity and allyship for . . . and support inclusion of marginalized people into the beautifully varied fabric that is America. We look forward to reading and sharing your poems, as well!

Final Thought

Member discussion