You’ve heard all the clapbacks.

“I have lots of Black friends!”

“My neighbours are Indian, they bring us over samosas all the time!”

“My brother is married to a Black man!”

And, of course, everyone’s favourite, “I don’t see colour!”

As if that proves the utter impossibility of their being racist. It’s laughable. It’s insulting. How dare you even suggest it?

People rarely react well when someone points out their racist behaviour. Point out sexist or homophobic behaviour, say, and they’ll try to laugh it off. But racism? We’re outraged. White people are incredibly touchy about being labelled racist. Most of us will declare we’re anti-racist and we’ve been misunderstood. But few of us are genuinely, actively anti-racist. Even fewer embrace anti-racism 101.

The True Foundation of Anti-racism

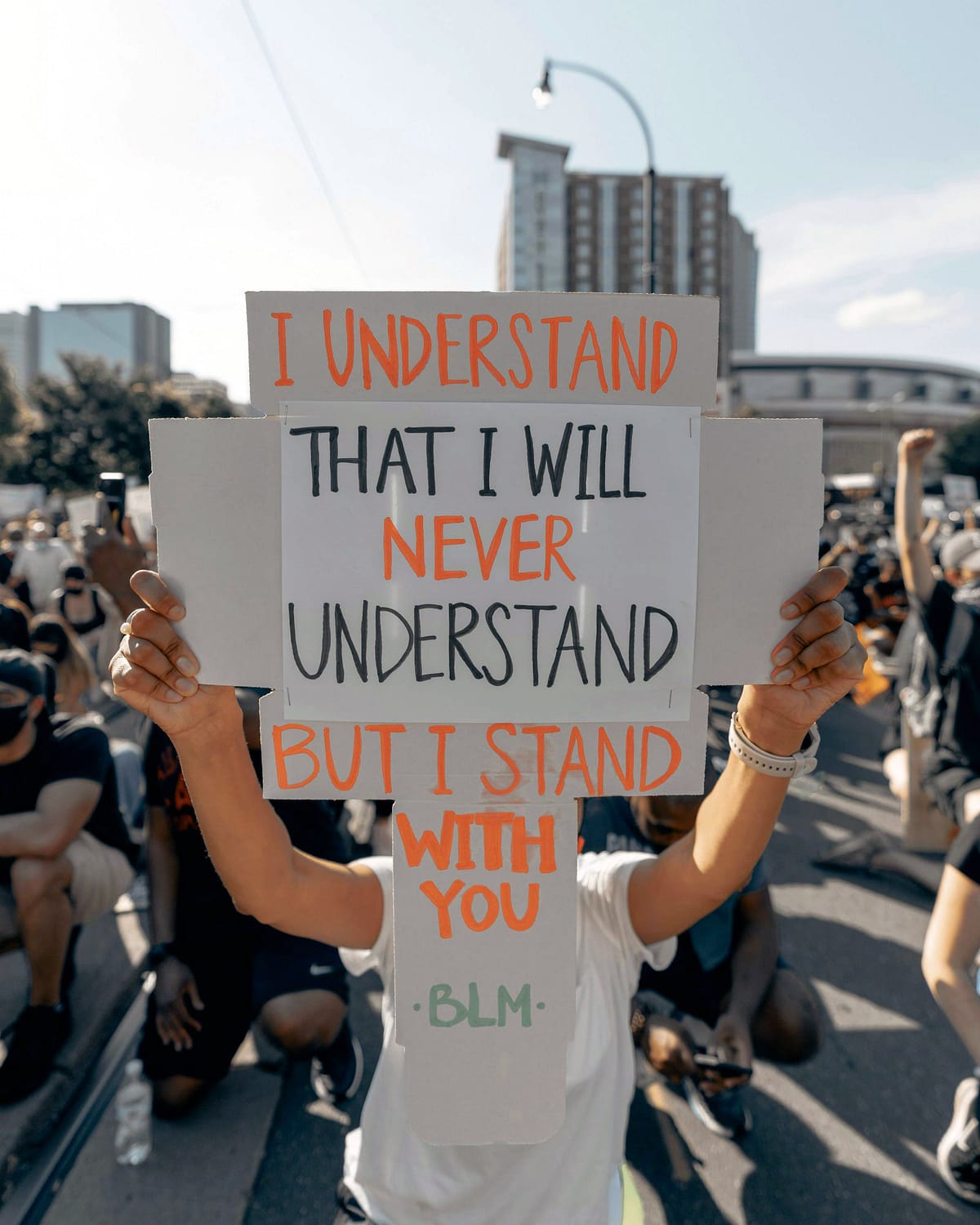

Approximately 99.9% of well-meaning white people like me approach anti-racism with the goal of being able to declare that we aren’t racist. We recognise that racism is a deeply rooted, centuries-old systemic injustice that has robbed millions of people of dignity, opportunity and life. We want no part in that, so we Do The Work.

For example, we diligently research the history of the enslavement trade and watch documentaries to educate ourselves about contemporary racism. We actively diversify our professional and social network to better understand the reality of living in a racist society. We can quote endless stats about the stark differences in educational, career, and health outcomes for the Black and Brown people who live in predominantly white societies. We speak up when we see or hear racism. We smile warmly at Black and Brown people in the street. “I see you,” we’re saying with that smile. We feel proud of ourselves for doing so. Because that means we’re definitely not racist, right?

Wrong.

The P Word

Apart from neo-nutters, the majority of white people fear being labelled racist. We’re easily triggered into exasperation by words like ‘privilege,’ ‘white supremacy,’ and ‘systemic racism.’ We’re outraged at the notion that we’ve benefitted from unearned privilege our whole lives.

“You should see my gas bill! You should see my mortgage!” we cry. “I’m not privileged! I’m barely getting by!”

I’m not talking about the kind of privilege that manifests in gated McMansions and luxury cars and our little place in Cyprus. I’m talking about the oblivious privilege of white skin being accepted as superior, and anything else being lesser. Even the term ‘Caucasian,’ a commonly used word to describe white people, is rooted in the notion of white races being superior to African and Asian races. Whatever difficulties we’ve experienced in our lives, the colour of our skin has not been a factor that’s worked against us.

Anti-racists acknowledge and accept that racism is deeply embedded in our society. But the vast majority of white anti-racists see the problem as being out there, not inside ourselves. We’re woke to it. We’re one of the good guys. But by acknowledging that racism is embedded in society, by default we have to also acknowledge our own racism. It’s been built into our psyche since we were born, whether or not we’re prepared to admit it to ourselves.

And the terrible, unforgivable reality is that it’s been socialised into the Black and Brown people who were born and raised in white countries. Back in the 1940s, two psychologists investigated how young Black girls view their racial identity. Given a choice between white dolls and Black dolls, the girls chose to play with the white dolls. They gave positive characteristics to them, and negative characteristics to the Black dolls.

Oh, that was the 1940s, you’re probably saying to yourself. Times have changed.

Sadly, that’s not true.

In 2021, Toni Sturdivant carried out the same research and found the same thing. Young Black girls would mistreat the Black dolls in a way that they didn’t treat the white dolls, for example pretending to cook the Black dolls in a cooking pot. Nothing has changed.

Where and how do Black children acquire this unconscious white supremacist mindset? Tragically, it’s all around them when they’re growing up, and particularly in their classrooms. Research in the USA and in the UK has shown that teachers typically favour white students over their Black and Brown classmates. Teachers are more likely to perceive white students as academically capable, respectful, and well behaved, and Black students as academically weak, disrespectful, and disruptive.

In a blind grading test, teachers assessed exactly the same story about a second grade student’s weekend. Half of the stories referred to playing with friends whose names sounded stereotypically white, half whose names sounded stereotypically Black. You won’t be surprised to hear that the white-sounding story was assessed and graded more positively than the Black-sounding story.

Kids aren’t stupid. Kids have a strong sense of justice. Black kids can see and experience for themselves that they’re treated differently, and they realise from an early age that they have to work twice as hard to get half the recognition that white kids get.

I’m racist. You’re racist. The sooner we can all acknowledge that, the sooner we can practically, tactically dismantle it from our society. But anti-racism conversations get shut down quickly by the majority of people who insist that they aren’t racist, and get angrily triggered by the idea of privilege and white supremacy.

Why We Get so Triggered by Anti-racism Terminology

Because it scares us in ways we can’t easily explain, and very few white people have the courage to examine their fear. Fear is the foundation of society’s failure to address racism. We reason that racism isn’t our fault. It’s been around for centuries. What if we do somehow dismantle systemic racism? Will there be fewer jobs and opportunities for me and my family? What if Black communities take revenge on white people, or bankrupt our countries by winning the fight for reparation payments?

That’s what we’re scared of, folks, and indeed, the genesis of racism isn’t our fault. But its continuation is our fault. And it’s our responsibility to do whatever it takes to put it right.

Why Anti-racism Training Doesn’t Make any Difference

Racism is a hot topic. Police forces on both sides of the Atlantic have come under intense scrutiny, and thousands of employees have been sent on anti-racism training courses. So why is nothing changing? Why are Black women still four times more likely to die in childbirth than white women? Why are Black men still five times more likely to be stopped and searched by police, and three times more likely to be jobless when they graduate from university?

I’ll tell you why.

Anti-racism training is aimed at educating people in the expectation that they will see the light and change their behaviour. But behavioural change doesn’t come about because of one workshop. And it doesn’t come about if the people attending the workshop don’t acknowledge and own their racism, and commit to being part of the solution. Raising awareness is a baby step. We won’t get rid of racism through awareness alone.

Anti-racism training makes white people feel uncomfortable. Guilt, shame, defensiveness, helplessness; these are just a few of the uncomfortable emotions we feel when we open our eyes to the reality of racism. Our brains are wired to move us away from discomfort. Our immediate response is to deny it, downplay it, reach for ‘facts’ and ‘objectivity’ rather than listening, believing, and taking action. We shut down conversations about racism or sit in silent discomfort, not knowing what to say.

A classic example of racist behaviour from an anti-racist is choosing not to point out racist behaviour when we witness it. Why? Because we fear making a mistake, saying the wrong thing, upsetting people, not being able to articulate our point properly or follow it up if it’s challenged. It’s easier to say nothing than to make a fool of ourselves.

When we don’t speak up, we’re displaying as much racism as the person we want to call out. We’re prioritising our comfort, and theirs. We’re betraying not just the person on the receiving end of the racist behaviour, but everyone who’s ever been the subject of racist behaviour. Because every act of racism that goes unchallenged maintains the status quo. Our fundamental desire for comfort overrides our desire to dismantle racism.

A Personal Example of Realising My Racism

A few years ago, I went to the launch of a report detailing research that demonstrated how gender equity has benefited white women at the expense of Black women. The event was held in a large auditorium in the heart of the City of London. There were perhaps 200 women there, with a sprinkling of men.

When I walked into the foyer of the venue, I immediately noticed that I was one of a handful of white women there. This is what it feels like to be in a minority, I thought, pleased with myself for noticing and naming my discomfort. Then I immediately checked my racism. Ninety minutes spent in a space with predominantly Black women gives me as much insight into being in a minority as accidentally walking into the men’s changing room at the swimming pool. What a patronising, racist thought.

Then we were invited into the auditorium. I found a seat, settled myself in, turned my phone on silent, then looked around. To my horror, and my intense embarrassment, I realised that I’d unconsciously sat down next to one of the few other white women. I didn’t know her. I didn’t know anyone. My subconscious had walked my feet towards someone like me. I spent the whole session miserably imagining the other audience members thinking (perfectly reasonably) oh look, there’s a living, breathing example of a white woman being a white woman. Thanks for coming along, sis.

It’s easy to beat ourselves up for mistakes, and I’ve made many of them, especially in the early days of educating myself and trying to articulate things that I didn’t fully understand. There are at least two people in this world who will never take a call from me again because of my inept bumbling and fumbling for words. The easy thing would have been to give up on the grounds that I was doing more harm than good, but that’s not how anti-racism works. I had to accept that there are people out there who think I’m a bit of an a-hole (or a lot of one), and I knew that I had to keep trying.

The more I leant into conversations about racism, the easier it got to articulate what I wanted to say, and the easier it got to retrieve a mistake when I realised that I hadn’t expressed myself well. That’s the best advice I can give you. Don’t give up. Apologise for your mistakes without demanding forgiveness, learn from them, and don’t give up.

How to Apply These Ideas

- Admit your racism to yourself. Acknowledge that it’s been drummed into you, with or without your knowledge, from the day you were born.

- Catch yourself making unconscious judgements and acknowledge them for what they are. Many Black boys and men will tell you how tired they are of seeing white women clutching their bags tighter when they pass them in the street. If you instinctively react to a Black or Brown person, notice it. Ask yourself why you had that reaction. Acknowledge the racism that was at play. The more you do this, the more you’ll realise how deeply rooted it is.

- Talk to other white people. Explain anti-racism 101. Encourage anti-racists who can’t bring themselves to own their racism by owning yours. If you acknowledge your racism, they’re more likely to do the same.

Key takeaways:

- Anti-racism work isn’t about proving that we aren’t racist. It’s about dismantling racism.

- Acknowledging and owning our racism is the foundation of anti-racism.

- Encouraging others to acknowledge their racism makes conversations about anti-racism easier.