Editor’s Letter

Before you start stamping out racism everywhere you see it, know that you’re going flail around on the floor like a newborn in your first attempts at being an ally. Now that you know what microaggressions are, one day you’ll find yourself in the grocery store, the gas station, or the mall and you’ll see a microaggression unfold before your very eyes. The impudent salesperson or cashier will dole out a heaping of disdain to an undeserving customer of color, as described in this book. You’ll note that customer try to shrug off the cashier’s callous display of racism as they leave. The moment will catch you so off guard you may stand there like a deer transfixed by the headlights until the cashier cheerfully calls you to the register.

[Cue: sad sax riff.]

Don’t worry, racism never takes a day off. Unfortunately, there will be thousands of opportunities for do-overs. In time you’ll crawl, stand up for an instant, take a step or two, stumble, and fall before you’re able to walk, run, or even sprint. Learning how to handle situations is a process, but that’s where the joy is: in the learning and doing. Trust me.

And why should you trust me? Because I’m a multi-discipline expert in confronting misconceptions. I’ve been Black every day of my life for over fifty years and during those fifty-plus years, my friends, I’ve been in a variety of situations in predominantly white spaces, and in every single one of those situations I’ve been Black. I attribute my longevity in part to knowing the ways of white people and how to navigate those spaces. It incumbent upon me—and all Black people—to know the ways of white people. The hollow smile, the false laughter, and the “Sure, I’ll take care of that,” that heralds betrayal. Our lives depend on knowing those ways and have for over 400 years. Truth be told, lest I sound pompous, I attribute my longevity to the grace of God which has kept me from encountering hardcore racists who despise my blackness so much that they would seek to do me harm.

Now add to the mix, the irrefutable fact that I am forty-eight-inches tall. Bet you didn’t see that coming! I’m not going to belabor the topic, but the takeaway here is that between people’s reactions to my ethnicity and disability (dwarfism), I’ve got more than enough experience with being “othered” dealing with people’s preconceived notions of what a Black man living with dwarfism is capable and incapable of. The upside is that I’ve had countless opportunities to either fold under pressure or transcend other’s prejudices, as well as my own. The vast majority of the time, I choose the latter. With that said, I might have a useful tip or two for you. Now let’s get to work.

Truth and Love

These two commodities—and I refer to them as commodities because they’re precious and not enough people have enough of either—are at the core, outer edges, and middle of serving as an ally. By standing up for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color in America or around the world, you are committing an act of love by speaking the truth against the lies of racism.

I’m not massaging your ego or touting how “good” or “moral” you are for traveling this road. I’m giving you the facts. When your compassion moves you to intercede on behalf of someone else, that’s love. Plain and simple. Countering racist thoughts, words, and deeds—which we know are rooted in irrational and unfounded beliefs—with facts extinguishes those lies with truth.

For most of us, though, engaging family members about polarizing topics is like walking through a minefield, and rightfully so.

When you commit to serving as an ally, instances of racism become more and more apparent. And I’m not suggesting you go out in search of a boogeyman behind every tree. The truth is, once you see the humanity in someone, you can never unsee it. So it stands to reason that when you see someone attempt to deny another person’s humanity or deny them the respect they are due by virtue of their inherent humanity, it will impact you negatively. On a visceral level.

Your words and actions will have the biggest impact on people you already know. Why? Because you already have an existing relationship with them. There’s a given level of trust that comes with any relationship. Your family, friends, and coworkers are more likely to take what you say to heart than a complete stranger.cFor most of us, though, engaging family members about polarizing topics is like walking through a minefield, and rightfully so. Who wants to be accused of ruining Thanksgiving all because we took the bait and dropped a truth bomb on a parent, aunt, or uncle who’s in their cups? Which brings us to the next point—

Timing

Timing is everything. There have been countless well-intentioned people who, in the name of allyship, have launched themselves into situations at the wrong time and have set their relationship and reputation with the people they hoped to serve ablaze as a cautionary tale of how not to be an ally.

Allyship requires that you assess the truth of a situation. Does the marginalized Black, Indigenous, or Person of Color need/want my assistance? Is it the right time to respond? Is it the right setting? Is it better to confront someone over racist words or actions in the heat of the moment, or would it be better to wait and speak to them privately at a time when they’re more apt to actually listen to what you have to say? These are determinations you’ll have to make on your own because there’s no one size fits all prescription for dealing with people and there are too many variables in play. Always try to make the best decision possible for those whose interests you’re supporting in any given moment without putting anyone in danger. But I guarantee you, with time, you’ll get better at assessing situations and determining when it’s a good time to get involved and when not.

When advocating for equality, you’re not offering people help with a check-out-line impulse purchase of a Snickers bar over a bag of Skittles. And you’re not selling them a car. Via your words and actions, you’re presenting a different way, a broader way, to see the world and everyone in it. Ultimately, you’re asking them to subscribe to confidence and not fear. Truth and not lies. Love and not hate.

One thing that is easy to lose sight of is that people don’t come to hold racist beliefs overnight. Hatred isn’t an online course they completed in six weeks. People mimic the behavior they see. And the longer they live in that environment, the more entrenched those beliefs become. No matter how desperately we want people to stop doing and saying racist things once and for all, truth is, it ain’t gonna happen that fast. Never does. Paradigm shifts occur gradually over time with increased understanding. Think about how long it took you to change your thinking about any number of topics.

Seeding and Weeding

Think of your actions as planting and nurturing seeds, and pulling out weeds. Seeding is anything that encourages a budding mindset that embraces racial equality. Weeding can be thought of as responding to a racist comment and can consist of expressing displeasure, pointing out inappropriateness, or expressing truth that neutralizes racist statements.

Use your best judgment as to whether it’s best to speak up or remain silent in a given moment. I don’t recommend that anyone put themselves in physical danger. Nor am I giving specific phrases to use as they are not magic words that will repel or compel an anti-racist mindset; what works for one person may not work for another.

For some people, it will take weeks, months, or even years before they finally come around and it sinks in. I write that not to give them a license to ill, but to remind you to breathe. Remembering this reinforces the notion that you don’t have to “fix” anyone. You can’t fix anyone. The decision to change is solely that individual’s choice.

Allyship is a process, full of ups and downs, hits and misses, gaffes, a few laughs, and successes.

I firmly believe that people can change. I say this because I know it can happen. I’ve seen it happen too many times to think it’s a freak accident. I know a number of people who grew up in patently racist homes who later discovered they were sold a false bill of goods about Black people and People of Color. The reality of their firsthand experience with People of Color didn’t match up with the negative stereotypes they were taught to believe.

It’s a pretty profound experience to find that your perception of the world is wrong, and that of the people who taught you is woefully incorrect. These folks were forced to reconcile the difference between the two and did so at their own pace. People can change when they want to change, when they believe change is possible, and when they know how to change.

There’s no sanctioned, universal infographic (that I know of) that maps the transition from a racist to an anti-racist worldview a person can point to say, “I used to be a Two, but now I’m at Step Four.” At the same time as you can’t say with surety, “Me? I’ve reached a 75% success rate in allyship.” It’s a process, full of ups and downs, hits and misses, gaffes, a few laughs, and successes. If you’re lucky, you’ll forge new relationships with like-minded people along the way.

In the meantime, all you can do is keep nurturing those anti-racist seeds and snatching out those pesky weeds. Chances are you aren’t the only person speaking to them about their beliefs. As an ally, you don’t have to be present when the fruit ripens. It’s more important to do what you can to help those anti-racist seeds take root. Yours and those of others.

Talking with Black, Indigenous, and People of Color About Racism

Now more than ever, people are talking about equality and race, but in order for two people of different ethnicities to have a productive conversation about racism, two mutually agreed upon prerequisites must be in practice—

- Speaking to one another with respect and care for the other person’s inherent humanity

- Actively listening with the intent to leave the dialogue with a better grasp of the other person’s point of view

—without these two conventions, even with the best intentions, the conversation will invariably morph into a shouting match with one person feeling marginalized and the other personally attacked. One factor that makes discussions of racial equality difficult is that some white people can’t accept the fact that a Black, Indigenous, or Person of Color’s firsthand experience is both valid and real. Why? The short answer: because it’s so different from their own.

A couple of years ago, I spoke about race with a very good white friend of mine. He is as far removed from the racial tension we seen on tv as anyone can be. His lifestyle is what anyone would refer to as upper-middle class. He has an open mind and based on our friendship of more than three decades, I can state the guy is no racist. A few days after our first in a series of in-depth conversations about race relations in America, he informed me that while I made no implied or direct accusation that he was a racist, my friend said he felt personally attacked.

This has been a common response from most of my white male friends. I informed him that our discussion of racism, bias, white privilege, and how they’re manifested by actual hooded, cross-burning racists, homegrown vigilantes, or Neo-Nazis was in no way an accusation of being a racist, nor was it a personal attack. I explained that I was communicating my firsthand encounters with racism. Without providing a transcript of the conversations, we moved forward in our understanding of one another and the issues at hand.

Snow

This is going to sound really crazy at first, but it’s 200 percent true: No Black, Indigenous, or Person of Color owes anyone an explanation of their experience with racism or justification for why they feel the way they do. Full stop. Granted, such a conversation can be beneficial, but curiosity does not outrank self-preservation. Living a life in the face of an onslaught of everything from microaggressions to murder is exhausting. And traumatizing.

Society doesn’t poke and prod victims of violent crimes or trauma to relive their experiences. “Hey, can you tell me about that time ‘x’ happened. Yeah, I know it may have been harrowing, but I’d really like to know what that was all about.” It’s rude, wrong, and an assault on human dignity. Don’t do it. Be forewarned, the response you receive may cut you off at the knees.

Would that be considered a “nice” response? No, but neither is racism. Is it appropriate? Yes. Maintaining one’s boundaries and self-dignity occasionally requires a firm admonition to those who would overstep said boundaries. If a Black, Indigenous, or Person of Color does invite you into such a conversation about their experience with racism, listen with the intent to develop a better understanding of their experience. Don’t question their interpretation or ask if they’re “sure” things happened the way they described. This is not a bridge to increased understanding. If anything, it throws up roadblocks and signals a lack of belief that the Black, Indigenous, or Person of Color is incapable of comprehending their own experience and adds actual insult to injury.

I can’t imagine how deeply that affected you, but I understand what it’s like to be human; to feel discounted, mistreated, and misunderstood. I’m here for you.

For those of you who doubt the stories of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color about what we’ve experienced, I offer you this hashtag to remember: #snow. Imagine you’ve lived your entire life in a tropical climate and you’ve never heard of, seen, or experienced snow. One day someone who lives in an arctic climate tries to explain the concept of winter, snow, blizzards, and all that comes with snow in the winter.

Your lack of experience with snow does not negate the existence of snow, the need for winter clothing, the accumulation of snowdrifts, and blizzards. To entertain the notion that snow exists, you have to concede that the world as you know and have experienced it is not the only way the world can exist.

A friend learned of an incident he suspected was rooted in racial inequity that happened to me, and said, “I can’t imagine how deeply that affected you, but I understand what it’s like to be human; to feel discounted, mistreated, and misunderstood. I’m here for you.” Those last four words opened the door to a deeper conversation about the incident.

Guard Your Heart and Other Body Parts

To say serving as an ally is challenging is an understatement, but it is rewarding work. You’re bound to encounter people who aren’t interested in what you have to say about equality and racism—of all ethnicities. Fear of change and what life will be like after the change are prime inhibitors of paradigm shifts. People will lash out or they may get physical. We’re neither condoning nor encouraging physical violence. That does nothing for marginalized people, their causes, or you.

Don’t take terse responses personally even though you are the person on the receiving end of those remarks. Their actions say more about their state of mind than yours.First and foremost, neither I nor any of the authors in this book recommend that you put yourself in harm’s way. But if you’re a six-foot-four, two-hundred-and-fifty-pound guy with hands the size of glazed hams, and you feel your size and presence will lessen the likelihood of someone causing a scene, that’s on you. Just make sure you respond wisely, and not hastily.

Personally, I think of myself as an accidental activist. Not all that long ago, I dreamed of resurrecting the romantic-comedy genre by writing the greatest screenplay of all time. Hey, priorities change. It may seem as if I fell into “this,” but I like to think Providence has led me here. I’m not one for demonstrations. It’s not that I think they’re unimportant. Demonstrations are the bedrock of this country’s founding, but they’re not for me. At forty-eight inches tall, large numbers of people coupled with up-close and personal views of people’s butts and elbows are overwhelming and undesirable. So that’s not my thing.

But I’ve found other outlets that are better suited to me and my abilities that still have an impact. Not to toot my own horn, but I always enjoyed writing. Years ago, I wrote an essay in response to conversations I had with non-Black friends about racism. Much to my surprise, the essay caught fire (the good kind) and led to many more. Those essays led to the creation of an online publication where I encountered more people with their own experiences and desire for a more racially equitable world which led to founding a nonprofit, and now this book.

I mention all of the above to say, fear not. There’s no way you can possibly know how your efforts can positively impact the world. You don’t need to. Despite all the do’s and don’ts, this isn’t about being what we call serving the world as an “ally.” It’s infinitely larger than that. All of this is about being better humans and can be summed up in three words: Love one another.

Originally published in Fieldnotes on Allyship: Achieving Equality Together.

Love one another.

Clay Rivers

OHF Weekly Editor in Chief

NEW THIS WEEK

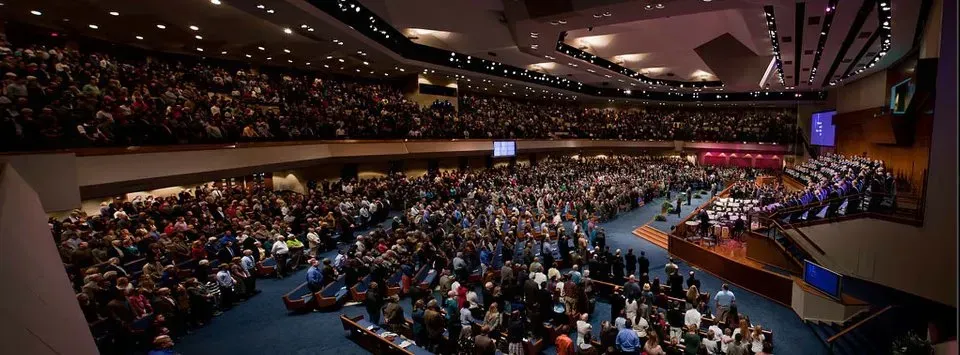

The Southern Baptists: Justifying Unchristian Values

The Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) is the world’s largest Baptist denomination, with over 13 million members. Their birth came from a split from the Triennial Convention in 1845. The division was mainly over the institution of slavery. The Southern Baptists favored enslavement, later segregation, and the Lost Cause Theory. Today you might think of them as the backbone of the religious right or the white Evangelicals that greatly influence Republican circles.

The Southern Baptists recently made news by kicking out congregations with female pastors, including the California megachurch Saddleback Church and Fern Creek Baptist of Louisville, Kentucky. Saddleback Church is led by Rick Warren, who wrote The Purpose Driven Life, which has been translated into over 50 languages and sold over 50 million copies.

While Warren is male, his church has women pastors, which is why they were expelled. In full disclosure, the Black non-denominational church I once attended used The Purpose Driven Life as a study guide for several weeks.

There are people who want to take the SBC back to the 1950s when white men ruled supreme and when the woman’s place was in the home. There are others who want to take it back 500 years to the time of the Reformation. I say we need to take the church back to the first century. The church at its birth was the church at its best. —Rick Warren

While Warren referred only to white male dominance in the 1950s, that policy began in 1845. Though church membership included small farmers and laborers, the control was ceded to plantation owners. The early Baptist Church competed with the Church of England, or the Anglican church, supported by general taxes. The Anglican Church opposed the spread of Baptists, especially in the South. Slaveowners Patrick Henry and James Madison defended Baptists from prosecution from requirements that the Anglicans license Baptist preachers. Thomas Jefferson wrote the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom that Madison used as a template when putting religious freedom clauses in the Constitution. The Church of England was disestablished, and the Baptist Church continued to spread, especially in the South.

Enslaved and free Black people were welcome in the church but only to a degree. Black people were segregated when attending white churches; they were allowed to have churches of their own which white pastors often led. Those with Black pastors were required to have white supervision. The Black churches were usually provided the “slave bibles” when Black people were encouraged/allowed to read at all. The “slave Bible” cut a significant portion of the Old Testament and some of the New Testament. For example, any reference to Moses setting his people free was omitted. The “slave Bible” became prominent in 1807 after the Haitian Revolution. I had the opportunity to look through one of the three remaining slave Bibles in existence.

Read the complete article at OHF Weekly.

Moral Bankruptcy: The Hidden Cost of Privilege

By Walter Rhein

I’m fortunate to be the father of two compassionate daughters who often take time out of their busy schedules to teach me important life lessons.

On one occasion, we were out on the lake riding a stand-up paddleboard. Rather than stand, I prefer to sit on the board and propel it with a kayak paddle. My kids are getting close to being too big for this activity, but a few years back we were out on the water giggling and having fun.

My youngest daughter was swimming. My eldest daughter was just along for the ride. My youngest was bobbling along, splashing, and calling for me to come in, so I did.

That’s when disaster struck.

After I’d played around for a few minutes, I went to climb back onto the paddle board and accidentally capsized it. This sent my eldest daughter into the water.

“Dad! I said I didn’t want to swim!” she scolded me.

“I’m sorry,” I sputtered, “it was an accident.”

From my daughter’s face, I realized that wasn’t even close to good enough.

I didn’t recognize it then, but my daughter was about to expose a critical flaw in my thought process. When there’s no greater authority present, it’s tempting to lean on the power of privilege to justify your behavior.

We spent a few minutes struggling to get back onto the paddle board. The good times were gone. My eldest daughter was absolutely furious.

“I really am sorry,” I said. “I just slipped when I was trying to get back on.”

“Harumph.”

I was eager to get back to the good times. I like making positive memories with my girls. I didn’t want to be stuck sitting under a storm cloud for the next twenty minutes.

In my desperation, my thoughts reverted to old tendencies. I was teleported back to the grade school playground as I remembered our go-to method for handling controversies like this.

“Look, you can push me into the water too, that will make us even.”

That’s when things went from bad to worse.

Read the complete article at OHF Weekly.

ALSO FROM OUR WRITERS

Provincetown: Built by and for the LGBTQ Community

By Glenn Rocess

A week ago as of this writing (June 1), I’d never heard of Provincetown, Massachusetts (so much for my self-assumed Jeopardy-level knowledge of history and geography, right?). It turns out that, like most cisgender people, there’s a whole lot I don’t know about the LGBTQ community—not only its history or preferred destinations but also about the people themselves. Even for those of us who have close family members who are gay, love them, and happily accept them for who they are (as I do my brother-in-law and nephews), much of what we straight, cisgender people consider to be knowledge is often mainly assumption and conjecture.

My wife and I are given to spontaneity when it comes to traveling. On Wednesday of last week, we decided to fly to Boston for a few days, just to check things out, and fortunately, the nature of our work allows us to do so on short notice. The next day, we landed, got our bearings, and began to explore the city. Our first impressions were quite positive: it was cleaner than and as modern as Seattle.

As we walked along Boston’s waterfront, we discovered that there was a ferry to the tip of the Cape Cod peninsula. We were eager to check it out, if for no other reason than to traverse the waters the Kennedy family had sailed so often and to see what was so special about Cape Cod itself. So we bought tickets and boarded the passenger-only ferry at 9:00 on Saturday morning. We arrived at the Provincetown Marina about ninety minutes later, and as we walked down the long pier to the waterfront, it didn’t take long to see things were a little different here in what the locals call “P-Town.”

Read the complete article at OHF Weekly.

Final Thoughts