Editor’s Letter

Florida, the state of my birth and where I currently reside, has become the tip of the spear for –isms, –phobias, and more. Every week, at least one new piece of legislation is passed that dehumanizes or strips rights from Black people, LGBTQ+ people, women, People of Color, or Jewish people. In case you haven’t noticed, that’s basically anyone who isn’t a cisgender, straight, white male.

The sunshine state has chosen to swap its once squeaky-clean reputation as a top international, family-friendly vacation destination for that of a haven for white supremacists, Nazis, hate groups, and their ilk. Just a couple of weeks ago, I spotted a lively group of folks in red shirts gathered on an Interstate 4 overpass. I couldn’t help but notice the white undershirts pulled up through the neck of their red shirts and over their heads, plus black sunglasses that shielded their faces.

At first glance, I thought nothing of the fashion statement because scads of lawn care workers don all manner of clothing to protect themselves from Florida’s subtropical sun. But unkempt yards are hard to find on overpasses, so nearby law enforcement vehicles’ flashing lights gave me a reason to pause.

Later that day, a report on the local evening news identified the protestors as Nazis.

As a registered voter who has had his Black-held Congressional district gerrymandered out of existence, rest assured when I tell you things aren’t as bad as you’ve heard. They’re worse.

In a state with a documented history of sundown towns and lynchings, one would expect to maybe find vestigial clusters of these hate mongers deep in the state’s rural areas, not out in the open waving crudely hand-painted often misspelled messages of hate within a couple miles of Orlando’s world-class theme parks. Florida’s reputation is so marred that the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) has issued a formal travel advisory regarding the state’s overt bullying and intimidation tactics fixed on the previously mentioned groups.

I am a realistic optimist, not given to hyperbole, who is a member of at least two of those marginalized groups. As a registered voter who has had his Black-held Congressional district gerrymandered out of existence, rest assured when I tell you things aren’t as bad as you’ve heard. They’re worse.

But that’s not the crux of my editor’s letter. I want to focus on a handful of Floridians I encountered who are actively living out the version of Florida I’ve always suspected was possible. This editor’s letter (which I’ve started, trashed, and restarted again about five times now) is my first attempt at putting thoughts to digital paper since my mother suffered what can best be described as a freak accident at home. It should also explain my missing-in-action status across my personal social media accounts and those of Our Human Family. So, if you'll indulge me, let’s begin.

As the matriarch of our family, in much the same tradition as her mother before her, my mom is loved by a great many people. That is a statement of fact, not an exaggeration. For her birthday, she made it clear she was loathe to participate in anything remotely resembling a major production in her honor. Instead, she told my siblings and me, if there had to be a get-together, she preferred something small with only a few people. Wise choice, given that Covid is still a thing. Think about it, people don’t live to be ninety by taking unnecessary chances.

At first glance, putting together a little birthday gathering seems like an easy task. And it is. Unless you have a large extended family like ours. My mother is the second oldest of ten children. That alone made for nine aunts and uncles (of which only four aunts and uncles remain), almost three dozen first cousins, and an unknown number of second cousins, spouses, and exes—just about all of whom adore “Aunt Connie.”

I’d be more than negligent if I failed to mention my mother’s thirty-eight-year career as an elementary school teacher. Think Sheryl Lee Ralph’s Barbara Howard of Abbott Elementary; all the respect and know-how, but none of the eccentricities.

My siblings and I managed to pull off a luau-themed gathering with around two dozen people in attendance. By all accounts, my mom was thrilled with the assemblage of family in requisite Hawaiian shirts, the Polynesian theming, and floral decor. All in all, everyone had a great time.

Three weeks later, a friend of the family stopped by to visit with my mom who escorted the friend into her sunken formal living room. Don’t judge. The house was built in the sixties when sunken living rooms were all the rage. Mind you, my mom has lived in the same house she and my father built fifty-eight years ago, and until that May 11, 2023, there had never been an issue with that modest four-inch step-down. As my mom was telling her friend to watch her step, the friend misstepped and fell forward onto my mom who broke her friend’s fall and sustained a serious injury.

Just so you know, once you enter an emergency room and if you’re lucky enough to be shuttled in one of those private holding rooms, you enter an alternate universe where time as we know it is stretched beyond the breaking point and hours seem to last as long as days.

My mother lay half-asleep on a gurney in one of those private rooms in the emergency ward, careful not to move her leg to avoid triggering the yet-to-be-determined source of piercing pain. Various nurses and an attending punctuated her catnaps to record vitals. And an X-ray tech wheeled in a mobile X-ray machine that not only rolled but also pivoted and rotated over and around patients unable to roll on their sides. It was amazing. I watched from a safe distance and snapped a photo of the X-rays that revealed the extent of my mother’s injuries. She sustained a broken femur, two-thirds up the length of her right thigh, and had no desire to see the photos.

After my mom drifted off again, I made time to steal away for a hallway call to an old friend who’s an emergency room surgeon at a teaching hospital in San Antonio. He took a look at the photos of my mom’s X-rays and told me her bones looked good for a ninety-year-old woman, and the break wasn’t the typical “old lady fracture.” He covered the optimal window for surgery, and what to expect over the next few days as well as the next twelve weeks of recovery.

What does any of this have to do with Our Human Family and the current state of the state of Florida?

A lot.

Racial equity, allyship, and inclusion are important to me, down to a cellular level. I see “color” and the differences some would use to divide and conquer the country as this nation’s greatest asset, not something to be feared and stamped out, and definitely not something to be weaponized in defense of white supremacy.

Not so long ago, the only faces I saw in hospitals were white. Some were nice and others not so nice.

Despite Florida’s attempts to whitewash American history and homogenize the state’s citizenry through fear and intimidation, I learned via direct observation over the next four days that the powers-that-be at one Orlando hospital were having none of the bigotry.

Full disclosure: during my mother’s time in the emergency ward the nurse, the attending doctor, and the X-ray technician appeared to be of three different ethnicities. There was no hint of negative racial bias among them—and I loved every minute of it! Don’t get me wrong. I harbor no ill will toward white folks, “some of my best friends are white.” Nor was I looking for a bad experience. My main concern was my mom’s condition.

But I am a Black man who’s lived in the South for most of my life and have encountered an innumerable microaggressions, ranging from covert to overt, so I am no stranger to racism. Or to surgeries. Not so long ago, the only faces I saw in hospitals were white. Some were nice and others not so nice.

My point is there had to be a concerted effort on the part of the hospital’s powers that be to employ an ethnically diverse team of doctors, nurses, and technicians. And the people of color weren’t relegated to the emergency room. Once my mother was taken to her designated hospital room, I would say roughly 70 percent of the people who cared for her over the course of her stay were People of Color—with one of her doctors hailing from as far away as Baghdad, Iraq.

There are those who wax poetic about “foreigners coming here and taking all our jobs,” or how they feel more comfortable with an “American” doctor—translation: a white doctor. If you’re bristling because you think this is an anti-white editor’s letter, just stop. Don’t get it twisted. This letter addresses representation in a state where erasure of all that isn’t white is de rigueur, if not the law.

The truth is both points of view are rooted in ignorance and prejudice. Teaching hospitals, like the one where my mother was transported, give great care because the residents are committed to attention to detail. Plus, doctors in teaching hospitals are always on the cutting edge of medical advances. In addition, personnel must be licensed by the state and credentialed by the hospital. This all but guarantees a much higher quality of care for patients.

Over the next four days, the nurses, doctors, et al transformed a traumatic experience into one in which my mother and I felt the staff was attentive and she was well cared for. And all this without an undercurrent of racism. Plus, I felt more at ease in the hands of a staff reflective of the city’s same heart and soul that came together after the Pulse massacre.

As of this writing, it’s been a little over two weeks since my mom’s accident. I’m happy to report she underwent surgery the day after arriving at the hospital and now has a titanium rod in her thigh. We found a nearby immaculate rehab facility with a caring and professional staff who—say it with me—adores her. She’s laser focused on her recovery and working hard to return to her pre-accident life at home.

Yes, the climate in Florida is openly hostile to Black people, LGBTQ+ people, women, People of Color, or Jewish people, and conditions are worse than you would ever imagine for any state in this country. But pockets of people are working to maintain an inclusive sense of decorum.

If you are disturbed by the recent spate of changes across the United States in general, and in Florida in particular, support marginalized people in their right to live peaceably and authentically. Now is not the time to sit idly by. Lives depend on it.

Love one another.

Clay Rivers

OHF Weekly Editor in Chief

The First Allies of George Floyd

This editor’s letter was originally published by OHF Weekly on April 2, 2021. We reproduce it in its entirety to commemorate the third anniversary of Mr. Floyd’s death.

By Clay Rivers

The trial of Derek Chauvin, the former Minneapolis police officer the world watched murder George Floyd last year, began Monday. On the day of opening arguments I mentioned my skepticism in any jury’s ability to deliver justice for Mr. Floyd’s family due to the lethal level of white supremacy and anti-Black prejudice baked into American society. A conviction of Chauvin on any of the three charges requires a guilty votes by all twelve members of the jury—a single hold-out and Chauvin leaves the court a free man.

Revisiting the murder of Mr. Floyd still traumatizes me. I purposely avoided watching the complete footage of his demise. The snippets I have seen of Mr. Floyd pleading for his life while being executed in a manner unfit for a dog is all I need see. I know how the story ends.

The work of advocating for racial equity is no crime, but an act of love.

If viewing the other footage presented of Mr. Floyd—whether laughing with people inside the Cup Food convenience store, sorting through the contents of his pockets, or emotionally breaking down at gun point with the police—is tough for me (which it is), I cannot begin to imagine the depth of grief and abject pain his loved ones are experiencing. Watching the trial must surely reopen their wounds. My heart breaks for them.

Judging from the witnesses’ reactions during their testimonies thus far, reliving the events of that day scars their psyches all over again. Today is Day 3 of the trial, and I holed myself away from the trial to write this article. On a brief break, I caught sight of an eyewitness on the witness stand, Charles McMillian, an older Black man with a white beard sobbing into tissues. The trauma is profound. And the damage palpable.

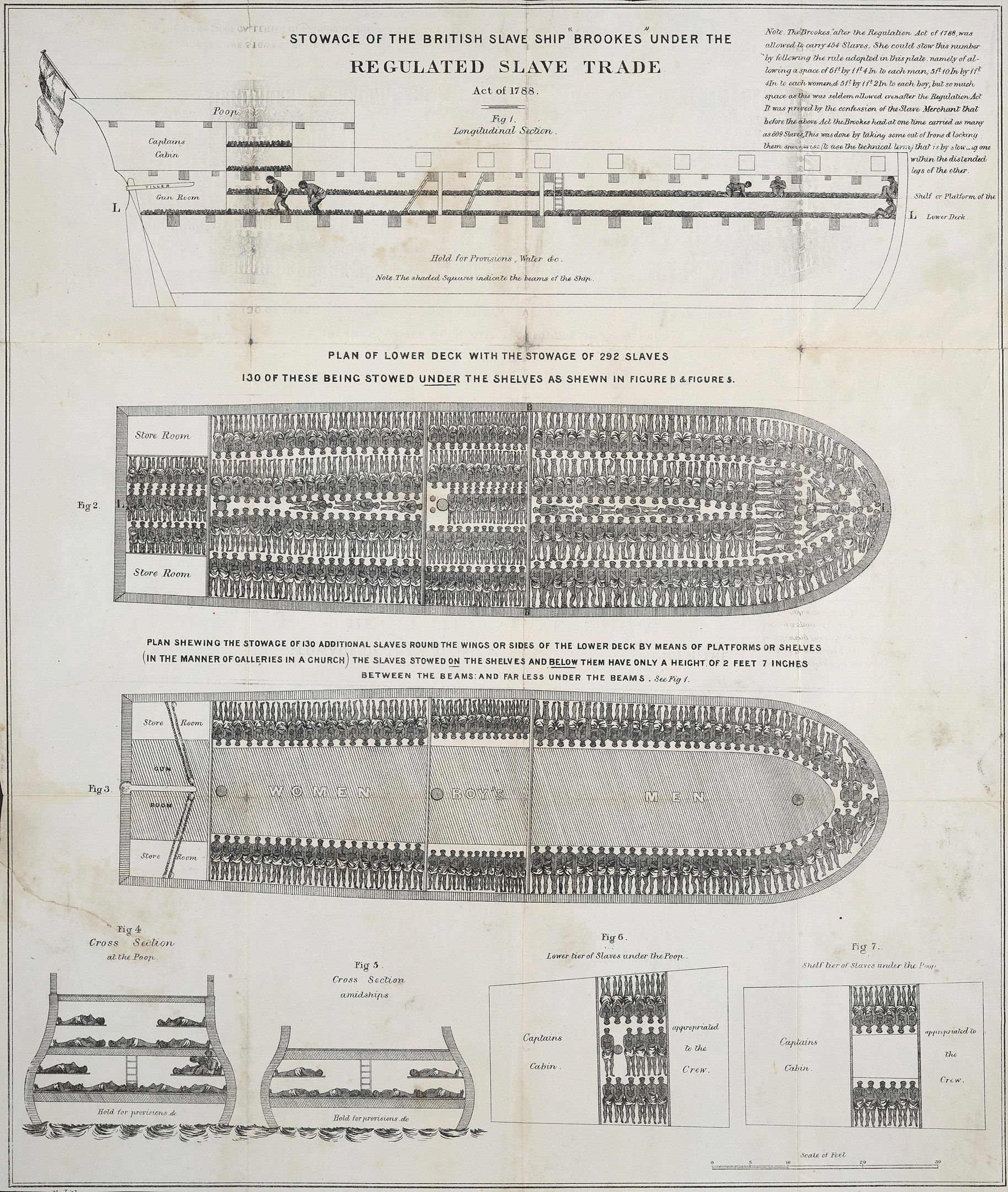

I am in no way the spokesperson for all Black people throughout the land nor do I pretend to be, but as a Black of a certain age, it’s safe to say that Black people the world over, especially those of us in America, are also being retraumatized all over again as well. The public execution of a Black man is nothing new in America. Since the São João Baustista arrived in Virginia with the first Africans kidnapped from Angola, before America was America, this country has demonstrated the lack of regard, if not disdain, for Black bodies. In the murder of George Floyd we see ourselves, family members, and friends who could becomes victims of a similar fate at any given moment.

In stark contrast to the brutality of the events of May 25, 2020, there is a lesson central to what is commonly referred to as allyship. But like everyone else, I use it out of convenience. Personally, I’m not a fan of the term “ally,” as it carries with it the notion that the services provided are performative in nature; rendered in exchange for approval, recognition, or some other reward. Nor do I embrace the label “accomplice.” People favor this moniker because it hints at one having skin in the game or something at stake. It flat-out implies the person(s) have or will commit a crime. The work of advocating racial equity is no crime, but an act of love.

Supporting Black, Indigenous, and People of Color in our pursuit of racial equity works best when it is rooted in the desire to hinder or cease the occurrence of social injustices by leveraging one’s self, gifts, talents, abilities, and/or advantages to benefit a marginalized person. But with that said, allyship in its purest form is simply being a better person. It’s being the best version of yourself, bringing that self to the fore, and being fully present in your advocacy when the moment calls.

One need only watch the testimonies of the first two days of the trial to understand this is exactly what each of the witnesses did. The people on the scene observed Derek Chauvin—enabled by virtue of his badge, service pistol, and the presence of four intervening officers—commit an act so heinous they felt compelled to act.

This is the core of being an ally . . . calling out racial injustice for what it is and speaking truth to white power via the means that are uniquely you.

They spoke out, pleaded, and attempted to reason with the officers, but whiteness coupled with a badge is a powerful drug, and they remained unmoved. The 911 dispatch operator call her supervisor and the police. The uniformed off-duty firefighter in the area attempted to give Mr. Floyd medical aid, but her efforts were rebuffed. And a teenager, Darnella Frazier, had the presence of mind and courage to record the cellphone video of Mr. Floyd’s murder in its entirety.

These ordinary people, each in their own way, neither shied away from nor ignored what they recognized as patently wrong. Because of their character and their decision to do what they could at the time, they can now tell the world exactly what they saw. The truth. Not “their truth” or some version of it. Judging from their testimonies, the impact of the truth in their advocacy just might deliver justice for George Floyd.

This is the core of being an ally. Not throwing oneself in harm’s way, but calling out racial injustice for what it is and speaking truth to white power via the means that are uniquely you. Be it in the grocery store, the workplace, the doctor’s office, or the schoolyard, racism needs to be confronted. Otherwise, the extraordinary becomes commonplace.

Tina Turner: Simply the Best

November 26, 1939–May 24, 2023

Known as “simply the best” and the “Queen of Rock and Roll,” Tina Turner survived heartbreak, abuse, and poverty, as well as the loss of two sons. She continued performing through it all and emerged triumphant, her powerful vocals, dance skills, and iconic look known the world over with songs like “Private Dancer,” “The Best,” “Proud Mary,” and “We Don’t Need Another Hero” (from the Mad Max Beyond the Thunderdome movie). Although Tina was almost seventy during her last tour, her indomitable spirit continued to shine through. She will live on in our hearts forever.

Enjoy this playlist of a few of our favorite Tina Turner tracks.

OHF Weekly Now on Mastodon

For the past four years, Twitter has been Our Human Family’s (OHF) social media channel of choice for communicating with our readers. Given the platform’s rapid and unabashed endorsement of much we oppose, OHF is transitioning to Mastodon. While we will maintain our Twitter account, know that the quantity of tweets from our account has noticeably decreased.

And if you’re curious about Mastodon and wondering which instance (server) to sign up with, mastodon.world (our instance of choice) is a fine instance indeed.

Final Thoughts