Letter from the Editor:

Justice Is Hope Enduring

What do you do when you realize that you’ve come to the end of your efforts and you find that you can’t fix something that really matters to you?

The question came to me after spending some time with my friends. Now, I’m white, and my friends are Black, and we’ve been meeting as regularly as we can—for twelve years it’s been about every week or so to check in, share stories, laugh, have some drinks, and just sit around the fire outside, rain or shine. Usually we spend the first few hours on superficial hows-the-family stuff and we share our success stories of what we did that we’re proud of and want everyone to know, but then we get into the meat and start going hard into the paint on the things that are perplexing us or hurting us or causing us to want to give up.

It’s the stuff we’re all dealing with in life. Mostly relationship stuff. Sometimes job stuff. Sometimes it’s money that is causing us distress. Sometimes it’s that we’re just damned tired. Sometimes—well, often—we have some loud talk about politics. But sometimes, when it’s very late and our masks are fully slipped off, we talk about race and our experiences. Not the casual and usual stuff that people can say just about anywhere in safe places. I mean the hard stuff where we dig into the raw pain and the despair.

This week it was something that exposed a very hard truth about living in this world. It came about because some of us have traveled out of country to visit Europe or Australia or various islands and we were talking about our adventures and exploits. Then the comment was made: “I can never visit these countries as a white guy. And I’d love to be able to do that because I’d love to be able to relax and enjoy the moment rather than feel like I’m sticking out.”

That stopped me. Here are my friends, world-travelers (sometimes courtesy of Uncle Sam) who during their excursions always know that they’re the odd man out. They can’t visit Europe or Australia without sensing that they are the ones everyone sees when they enter a room or step on a bus or enter a pub for a beer or rent a hotel room. They stand out, noticeably a stranger, and will always see the world as someone who is outside looking in.

My experience has not been that way. I’ve always been assured that while I might be a white male American, with all that such an identity implies, I can just blend in wherever I go because I look like the people where I visit. My parentage assures me of a connection on the European continent as well as the British Isles, and of course, if I visit Australia or New Zealand or Canada I look like the other Europeans. So I just take it for granted that I fit in. I didn’t think twice that my friends didn’t have that same experience.

So chalk one up to me again having a wake-up call to shake me out of complacency.

And as I listened to my friends speaking so wistfully about their travels and their experiences as always the Odd Man Out I also realized that there was probably not a damned thing I could do to make an appreciable difference.

The ways in which Black people are treated as the “other” are myriad, so strongly embedded in our world, so deeply planted and nurtured that striking down one injustice causes three more to arise in its place. It’s not just travel, of course. It’s housing and employment and justice and politics and the day-to-day living where people encounter the terrible costs of racism directed against them for no reason other than we can do this to you and you can’t change it. The work to overcome racism is just plain hard, sometimes exhausting, and it seems that it will never end.

But.

This doesn’t mean that nothing should be done. Perhaps the best thing about understanding the nature of racism in this way—so deeply entrenched that it appears intractable—is that we become sharp realists who stop worrying about good feelings and even worrying about acceptable behaviors. When we get our eyes opened to the difficulties of changing human behavior in this manner, we lose our privilege of thinking that we will have it easy and that a single moment of victory is enough to declare the battle over.

This isn’t a fun thing to realize, but it’s realistic. The work of creating justice, of expanding freedom, of bringing people into equality, of making incarnate the ideas expressed by “love one another” is work, not sunshine and daydreams. It is the conversation at work during hiring practices to demand that we consider actively seeking out Black candidates and others. It is the interruption in a family get-together to state clearly that disparaging Black people is wrong, no matter what displeased looks we get from Uncle Bob and Aunt Betty who are just “set in their ways.” It is in the discussion with a pastor about using language in preaching and teaching that connects color with saintliness or sin. (“Black was my sin until I was washed white as snow” is going to have an effect on everyone who hears that, and it’s past the time where we should be eliminating this poisonous language from our theology and our hymns.) It is pointing out, tirelessly, that the promises made in America that we are a people who are free and brave, at liberty to live as we will and protest as we will, means that everyone must given the same freedom to kneel or stand or sit no matter the efforts to require us to comply.

What I’m saying isn’t that we should just give up because it’s hopeless. What I’m saying is that when we have that moment of truth where we realize this is just going to be an endless, grueling task we can make the better commitment because now we know this isn’t something we’re doing for the feelgoods and backslaps but for justice and love and hope.

I can’t make it true for my friends that they can travel as if the world is not racist. At least, not yet, and not by myself. But in understanding their pain and their humanity, in seeing them, and looking to myself, I can hold on to this: while I can’t do everything, I can do some things, and I intend to do all that I am capable of doing. I am neither a fixer nor a savior. I am just their friend who would want them to be treated with the same kindness and access and freedom that I have. Because what is a friend if not someone who hopes for the best in the people whom they love?

I saw this quote recently and it resonates:

Hopelessness is the enemy of Justice.

~ Charlie Edward Dates

So in spite of the thoughts that it is just going to be very very hard to get justice done, I’m going to continue plugging away. Because I have hope as small as the grain of a mustard seed but I think it’s big enough to change the world.

And what is justice if not hope enduring?

In This Issue

- New This Week: “Awareness and Education: Creating a Beautiful Future” by Consuelo Flores

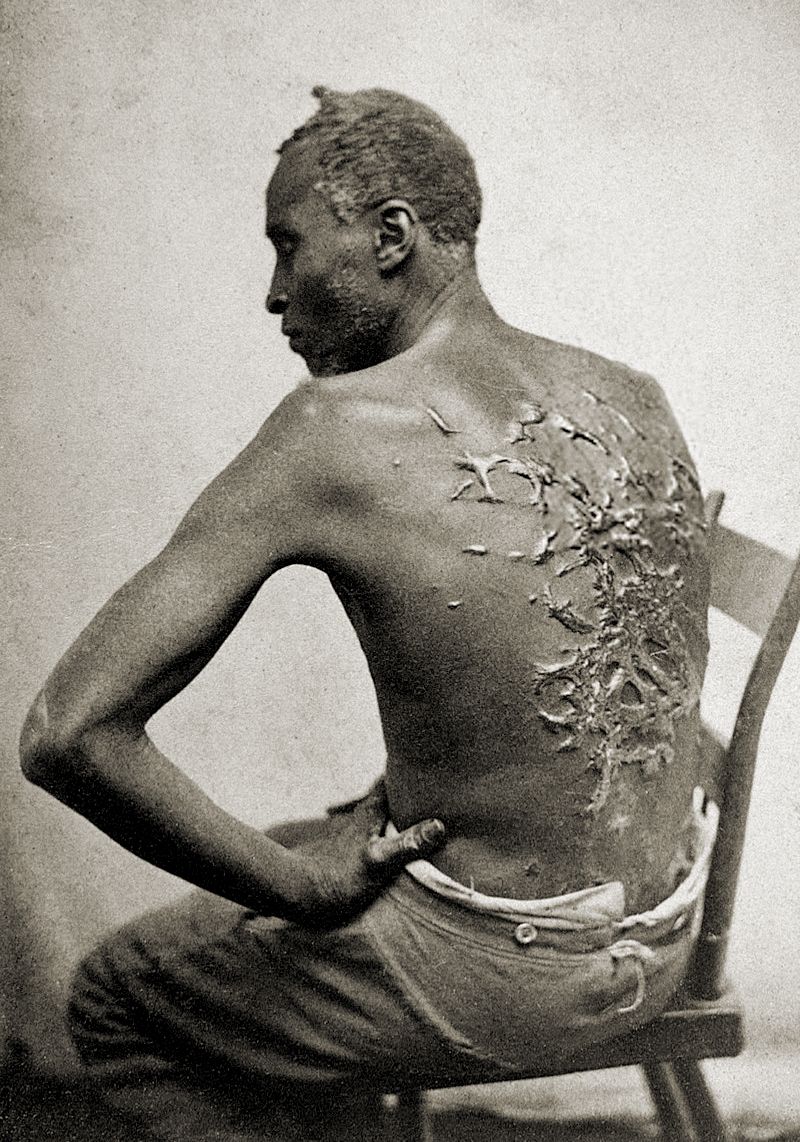

- In Case You Missed It: This week’s legacy article is “The Invisible Scars of Microaggressions” by Marley K.

- Promo: Our writers talk about James Baldwin—what his vision means to them and what they take for themselves in living out their own lives.

- Final Thoughts

New This Week

Awareness and Education: Creating a Beautiful Future

by Consuelo Flores

I have taken it upon myself to learn as much as I can by reading and talking with my Black friends and colleagues about their experiences—their hard truths, even and particularly now.

In Case You Missed It

The Invisible Scars of Microaggressions

by Marley K

White people may never know what it’s like to be Black, but I do. And as long as I have breath in my body I will talk about the impact of racism, white supremacy, and microaggressions on Black people.

OHF Magazine: The Baldwin Issue

James Baldwin, one of America’s foremost authors, activists, and playwrights, who addressed the themes of race, the political promise and peril of America, and the human condition, is the muse of this issue of OHF Magazine. We planned that Baldwin would be the muse for this issue back in fall/winter 2019, unaware of how prescient his words would be or the challenges we would face in 2021. And so in this magazine, we offer you interpretations of James Baldwin’s wisdom from the past written by people of different backgrounds and experiences who live their lives committed to justice, equality, and love as the proper means of moving into the future together in our human family.

Final Thoughts

Love one another.

Stephen Matlock

Our Human Family, Senior Editor

Top photo by Martin Reisch on Unsplash

Member discussion