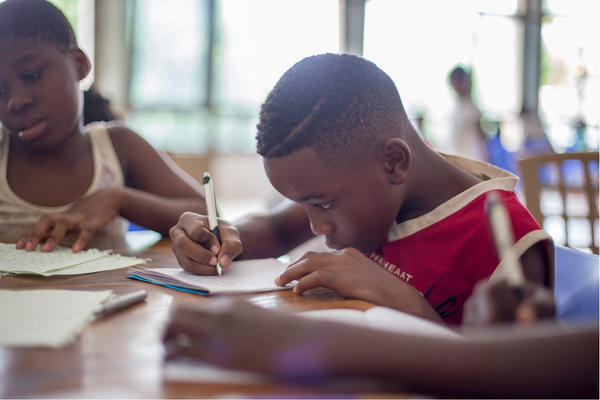

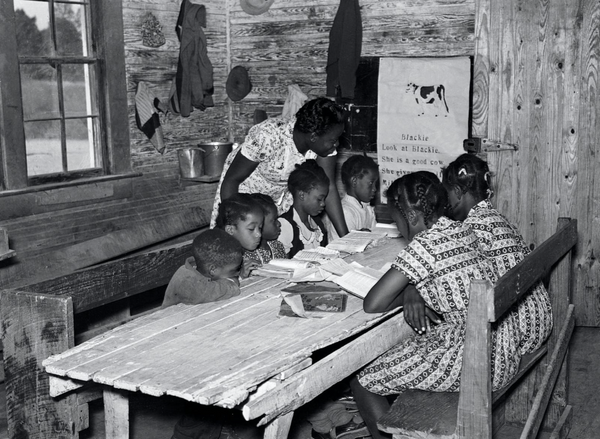

Did you know every black person has a PhD? It’s not the kind of education you acquire while attending a university. It isn’t taught in the comfort and safety of a classroom. It’s an education none of us actively pursue, because it’s thrust upon us from the time we’re born.

Every black person has a PhD in racism. We learn how to recognize it, how to work through it, and how to survive assaults that happen our entire lives. We come about this education in different ways, but we are enrolled in this continuous curriculum whether we want the lessons or not. Most black people get their harsh introduction into the school of racism when they’re too small to fully process what’s happening.

RELATED: “Ask Any Black Person, and They Can Tell You the First Time They Were Called a Nigger”

I remember the first day when my education began. I was a small child who knew little outside the love and support of my family and friends. I was playing at my white friend’s house while my mom was at the store. I was seven years old. My friend was five. I asked her if I could use her bathroom. She went to ask her parents. She came out carrying a roll of toilet paper and said, “We don’t let niggers in our house.”

She held out the toilet paper to me. I took it and went behind a bush in their yard and choked back tears as I squatted in the dirt and leaves. I don’t remember anything that happened immediately afterward. Weeks later, I told my mom what happened. I never played with that girl again.

“We don’t let niggers in our house.”

I did what many black children do when the violence of racism barges into their world in the form of white people who hate them because of their skin color: I endured the pain until the hurt eventually became a dull ache.

But I never forgot about it.

Years later during my freshman year in high school, I was walking down the hallway and passed two white boys. I recognized one of them most of my life, but we were never friends. I don’t remember us even speaking. One of them shouted, “Nigger!”

I felt like he had punched me in my stomach. The weight of that word engulfed me. It assaulted my senses. I turned and looked at his face, which was flushed a deep red. He looked disgusted as if my very existence made him furious. I had to see that boy for the next three years until I graduated.

I was fourteen years old.

I was no longer in the introduction to racism phase of my education. I was well on my way to becoming an undergraduate student in the course study. I didn’t yet understand the reach of racism. I still believed that, if I worked hard, that would be enough for me to achieve my goals.

For the most part, I loved college, I had several good professors. They challenged me. In my junior year, I enrolled in a “Women in the Media” class taught by an older white woman. There were only two black students in the class — me and another black woman. We became good friends.

It was clear from the beginning, the instructor hated us.

One day the class was discussing affirmative action. Several white students said it was unfair that anybody should get a spot in college just because they were black. The instructor didn’t explain affirmative action, nor did she dispute any comments about affirmative action being unfair to white people.

A male student turned to me and loudly asked, “How did you get into college?” The class went silent. I replied, “I graduated in the top 10 percent of my class. How did you get in?” He didn’t answer, simply turning away. The instructor? She said nothing about the entire exchange. She stood smirking in front of the class as if amused by the interaction. She showed no regard for the harm inflicted upon me and my friend. At that moment, I understood what I was up against.

We were one month into the semester.

Toward the end of the semester, the professor was returning our research papers to us. I heard my friend mutter angrily under her breath. I looked over and saw red slashes on the top of her paper. The professor had written a large “0” and the word “Plagiarized.”

She treated us like we were trespassers in her class. Now she had gotten rid of one of us.

My friend raised her hand and vehemently denied she had plagiarized. The professor replied, “You cheated. Gather your things and get out,” and pointed towards the door. My friend picked up her book bag and walked out. I heard her sobbing as she walked down the hallway and out the front door.

I believed her, not just because she was my friend, but because she worked hard for her grades. Throughout the semester, the instructor rarely acknowledged either of us in class. We weren’t called on to answer questions or add to discussions. She was only interested in teaching white students. She treated us like we were trespassers in her class. Now she had gotten rid of one of us.

You may ask why I didn’t report her to the chair of the department. At that point, I was getting a fairly advanced education in racism and the course work was a quick study. I knew they wouldn’t believe me and nothing would change. I was smart enough to know that, if this white woman was so blatant with her hatred, I would have been asked to leave class, too. Chances are her superiors were probably already aware of and supported her in her opinions. Maybe she would have had me expelled from college. I was graduating the following year, and I didn’t want anything to get in the way.

I was twenty years old.

I started my first real job at the age of twenty-one and didn’t know about microaggressions at the time, but my crash course in the subject began from the minute I started working. People said I talked too much. When I talked less, I was criticized for not contributing. One person complained that I was too friendly. Another said I was rude.

Amongst all these conflicting comments, I heard many times how well-spoken I was.

RELATED: “White People, When You Call Me ‘Well-Spoken,’ This is What You’re Actually Saying”

I’ve heard this “well-spoken” comment in various forms the majority of my life. I finally understood that it wasn’t a compliment. It’s a slight against my people, insinuating that we’re all stupid because we don’t speak the way white people think we should. By the time I was twenty-five, I understood this was a red flag and the person saying it was someone I needed to watch carefully.

I also heard many of these same white people say they don’t see color. In my twenties, I didn’t have a good response to this. I only knew it made my stomach drop. Somewhere inside me, I understood those white people didn’t see me. They refused to see me. Erasure and invisibility are too indignities regularly perpetrated upon black people. While I didn’t know how to respond to the color blindness comment, I was on my way to fully understanding how much white people did see color.

The majority of my education on racism has occurred while working with white people. I would attain my PhD in my thirties while working my first corporate job. It would be my last.

RELATED: “I Was Harassed at My Job and Left to Tell About It”

The harassment began almost immediately. A white male coworker — I’ll call Greg — oversaw my team. He ignored me and only referred to me as “she” and “her” when talking about me to coworkers. Greg never said my name. He only spoke to me when he couldn’t avoid it. My manager, a gay white man I’ll call Allen, said he would move me to another team. Weeks, then months, went by and the harassment continued. I asked my manager when he would move me to another team. Instead of being supportive, Allen said curtly, “Just do your job.” The harassment progressed to Greg and Allan criticizing my work and my attitude. Other coworkers told me both men were speaking disparagingly about me behind my back. I endured their behavior for eight years. Finally, I left.

I was thirty-six years old.

In that time, I gained a full, working understanding of systemic racism, white supremacy, and misogyny. I left wounded and angry, but I also left there smarter. I understood that, even when they see racism, most white people will remain silent. In my case, Greg’s behavior became my problem because I spoke up about his actions toward me. Both Greg and Allan gaslighted me from the time I walked through those doors. Later on, other managers joined in the abuse, and every day became a master class in racism. Years later, I finally understood what happened to me and why.

So here I am, armed with a PhD in racism that I have paid for, not with money, but in intimidation, humiliation, and fear. Even now, as part of my continued post-doctorate education in racism, I’m enrolled in two courses, “White Women: Their Role in Black Oppression and White Supremacy” and “Advanced Microaggression: Racism in the Public Service Workplace.”

Black people are enrolled at birth for a lifetime of racism classes. The never-ending full load of coursework can result in frustration, anger, and fatigue, but black people demonstrate our unique strength and resilience. Despite the obstacles thrown in our path, we rise and succeed. That’s not merely an accomplishment, it’s a miracle and a testament to who we are.

Photo by Eye for Ebony on Unsplash.