The practice of separating people based on race was nothing new when Black people challenged the status quo in 1954. In fact, it wasn’t even the first time they attempted to overthrow the practice.

After Reconstruction in the southern states, lawmakers created segregated spaces for Black and white people to not only stop the two groups from commingling but to disenfranchise and subjugate Black people. It was during this time Black people first challenged the laws that relegated them to inferior spaces and forced them to live as second-class citizens.

Plessy v. Ferguson

During a train ride in 1892, a Black passenger refused to ride in the train car designated for the Black passenger. Police forcibly removed the passenger, Homer Plessy, from the train and arrested him for violating a law that demanded the separation of the races in train cars. After being jailed, he went before the presiding judge John H. Ferguson in a New Orleans court. Ferguson convicted Plessy of violating the Separate Car Act when he refused to exit the whites-only train car.

The conviction prompted Plessy to sue judge Ferguson, in Plessy v. Ferguson, stating the judge violated his constitutional rights by depriving him of the “privileges and immunities” that came with being a US citizen. The Supreme Court did not rule in his favor, on the grounds that it was not unconstitutional to implement a law that “implies merely a legal distinction” between the races. The court cited an earlier ruling regarding the separation of Black and white students in school facilities as a precedent.

The caveat to the ruling was that the facilities created to separate the races had to be “equal.” This ruling allowed the US to continue to oppress and deprive Black people of their rights for the next sixty years. It was under these conditions they again challenged the existing state of affairs.

What Separate but Equal Really Looked Like

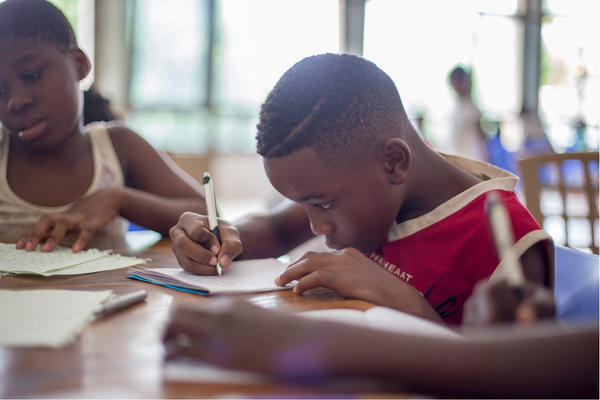

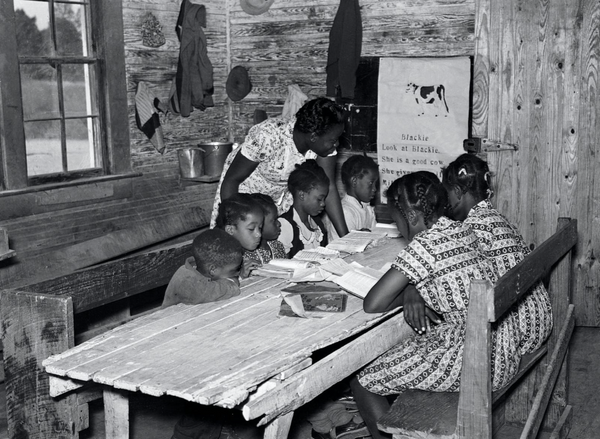

During the thirty years before Brown v. The Board of Education of Topeka, schools in Black communities only taught students what they needed to know to get the work designated for Black people. This meant manual labor jobs. Many white people worried that teaching them more than the basics of reading and math would inspire Black people to want to go further in school. And having a college education would prepare Black students for more than just sharecropping and housekeeping work.

White southerners had no use for educated Negroes, so Black schools received less funding than their white counterparts. This resulted in much smaller, often dilapidated schools, outdated textbooks for Black students that were no longer wanted in white schools, and a shorter school year for black schools than the white schools.

Because white teachers could not teach in Black schools and Black teachers often only attended ten years of school themselves, the education Black children received lagged that of white children greatly. This was often the case even in instances where Black people received a full twelve years of schooling.

The discrepancies in funding, curriculum, quality of training materials, and lesser qualified teachers continued to damage Black children for decades. During the early 1950s, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) filed lawsuits in Delaware, South Carolina, Virginia, and Kansas to challenge the laws.

Brown v. Board of Education

Several cases made it to the Supreme Court, but the most famous one is the class action suit filed by Oliver Brown against the Topeka Board of Education when they denied his daughter, Linda Brown, enrollment in an all-white school.

Brown contended that his daughter would receive a higher quality of education in white schools because they were better funded, had smaller classes, and better facilities. He felt Black and white schools were not equal and segregation of the schools violated the protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Kansas US District Court voted against Brown, stating that even though segregation was harmful to Black children and contributed to “a sense of inferiority,” the facilities were still equal under the law.

This led Brown to appeal all the way to the Supreme Court. His case was combined with four others filed by the NAACP that challenged Jim Crow segregation laws in different states. This is one reason we know so much about Brown’s suit and not the four other cases that made it to the Supreme Court.

Finally, a Ruling in Brown’s Favor

Thurgood Marshall, who later became the first Black American to serve as Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, was the head lawyer who presented the case on behalf of Brown and the four other plaintiffs.

Plessy v. Ferguson played a role in the decision, with then Chief Justice Fred Vinson believing the case’s verdict deciding that Jim Crow laws were legal should stand. Luckily for history and Brown, Chief Justice Vinson died before they decided the case. His replacement, Earl Warren ruled in favor of Brown, stating:

In the field of public education, the doctrine of separate but equal has no place since segregated schools are inherently unequal.

The Justices decided that Brown and the other plaintiffs were, in fact, being deprived of their constitutional rights of equal protection under the Constitution’s Fourteenth Amendment.

This landmark decision prompted a battle to finally integrate the school districts in both the north and south. But Brown v. the Board of Education was the first step in eliminating the laws that for so long had held back and harmed so many Black men, women, and children.