We sat on a park bench under the summer clouds.

Strangers, brought together by nothing more than the happenstance of being in the same park on the same evening and needing the same horizontal surface upon which to eat our picnic dinner.

We were three: myself, a woman of European descent, and a seven-year-cold Mexican boy who regaled us with stories of dinosaurs and warlocks who were really just boy witches.

“But I don’t know why they have a different name for boy witches because they’re really all just witches, and why do they need a different name if they all have the same powers?”

Why, indeed.

During a pause in our education, I asked about his mother. She was on the outskirts of the park because “she doesn’t think her English is good enough,” and despite being only seven, the literal metaphor of her not being invited to the table was not lost on him. He began talking about inequality and social justice with a subtlety that few adults manage.

“You don’t want to blame people because they are mostly just working and trying to make a living, and they don’t really want things to be unfair, but it’s hard to make things fair when you have to work and take care of your kids, but I always wonder why they don’t want to help more.”

Why, indeed.

That boy was smart, and listening to his grasp of race and class made me think that perhaps Latino children were given The Talk the way Black children were. I was just about to ask when I realized that I had lost the thread of conversation in thought, and was being asked a question.

“You know him, right?” he asked, obviously for the second time. The woman, too, was looking at me.

“I’m sorry, who?” I said.

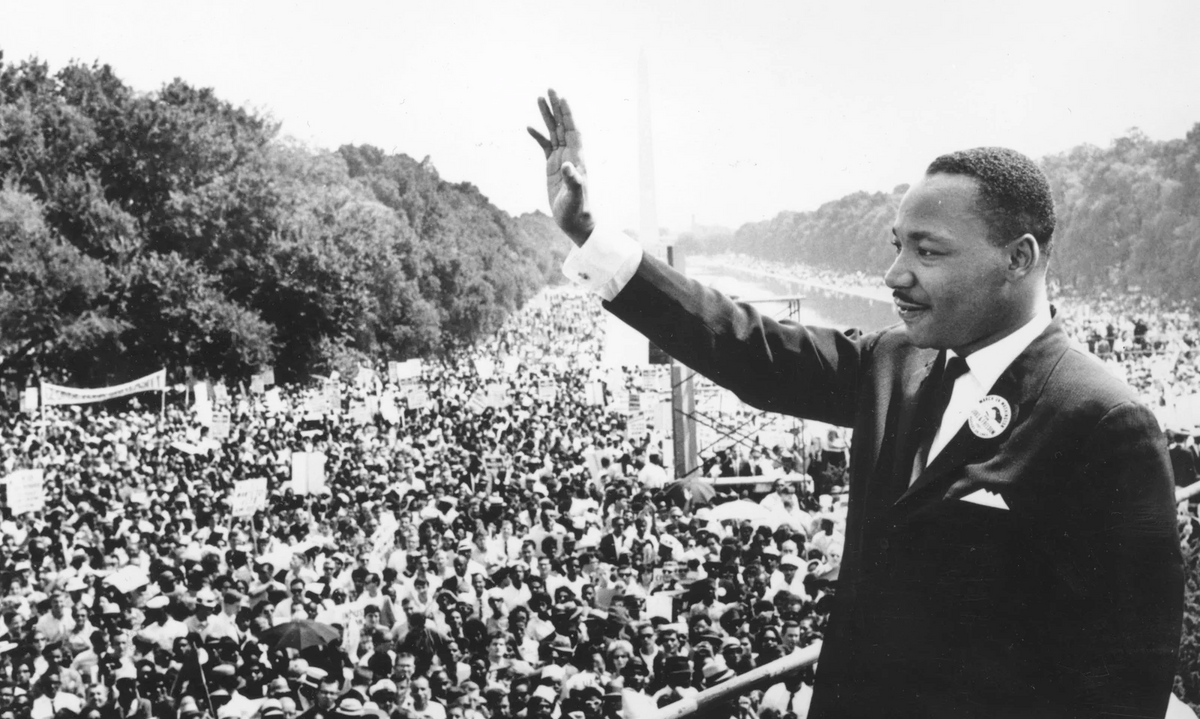

“Martin Luther King,” he said. “He was great, I love him. You look like him.”

I told him that I really did not, but that I understood what he meant.

“He was really cool. He did a lot of good things.”

It was then that the woman spoke.

“Do you know why Martin Luther King was important?” she asked him, in an oddly aggressive voice.

The boy hesitated and did not answer.

“Do you know why?”

“I thi–” I started, but she cut me off.

“No, it’s important that you understand this,” she said, looking seriously at the boy.

The boy was confused, as was I. It was obvious from his earlier statements on race and class that he was quite knowledgeable about Dr. King’s import. Yet he couldn’t answer. The voice of a grown-up had asked him An Important Question, and he was afraid of getting it wrong.

After being cut off, I too was silent.

“Martin Luther King is important,” she continued, “because he stood for something that people all over the world believe. He stood for equality and for peace and for non-violence. That’s why he’s important, because those things are important to everyone, and he taught us all to believe in them.”

Something bugged me about that.

At the time, I couldn’t get to the core of it. Was it her dismissal? Her lack of consideration for the nuance he expressed? I thought at first it was simply that here was another example of “The Invocation of King.”

Many have written about white invocation of Dr. King (and Rosa Parks, see Hillary Clinton’s wretched attempt at symbolism). Just searching Google for “invoke” with those names reveals dozens of articles and essays describing white people’s tendency to invoke (and claim) Black civil rights activists and arguing why they should not.

Nine months after that interaction, I’ve finally realized the core of what bugged me: Martin Luther King is The Magical Negro.

For those who don’t know, the Magical Negro is a literary trope that portrays a Black person as a supporting character to a white (most often male) protagonist. The Black person is always harmless, safe, and domesticated. They often seem to (or actually) have magical powers and they exist purely as a way for the white person to reach salvation or enlightenment.

Think of Stephen King’s The Green Mile, or The Legend of Bagger Vance, or . . . well . . . just about any role Morgan Freeman has ever played.

The Magical Negro is everywhere. It seems like an honorific, positive portrayal of Black people. But it always places a Black person in the subordinate role, helping a white protagonist’s journey. It diminishes Black people, yet again, to a one-dimensional stereotype; one that exists purely to support the story of a white person.

That is what Martin Luther King has become: a trope that can center the hard work of white America. Martin Luther King’s importance is that he helped white America reach its salvation of racial equality.

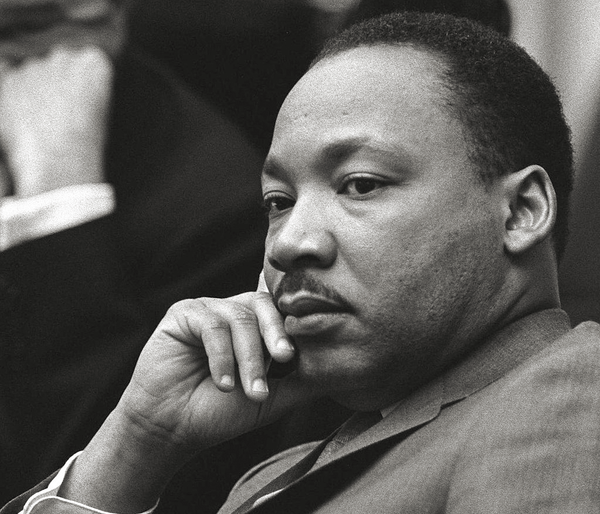

Of course, it’s ludicrous. While he was alive, Martin Luther King was possibly one of the most hated men in America. The government had him wire-tapped and considered him a national threat and at the time of his activism, white America would have been happy to see him put away or worse.

Yet today, even borderline racists invoke his name. The peaceful, non-violent Martin Luther King — much like the sweet, innocent, and mostly silent, Rosa Parks — is claimed by white people as if he is a talisman of redemption.

And he is. The Morgan Freeman character that Dr. King has become allows the narrative to center around white people overcoming racism. As Julian Bond quipped: “Rosa sat down, Martin stood up, and the white kids came down and saved the day.” This common narrative gives no value to the Black struggle, nor to the complexity of the Black people who organized, and fought, and died, to make the Civil Rights movement happen.

How many of the white people who invoke Dr. King as a symbol of non-violence appreciate his complexity?

How many know that he owned guns? How many know of his sexism? How many white people even consider the sheer organization and Black agency involved in the Civil Rights movement?

The history almost reads as if the Civil Rights movement was about to happen anyway. The image we see is of Rosa Parks, a meek little seamstress who randomly decided one day that she’d had enough. That random action was all it took to make it all happen. The reality is that she was a well-trained activist and that bus protest was part of a planned and organized rebellion that spanned decades. A Rosa Parks — any Black person — as an aggressive force fighting her own battle is something white society has always been loath to accept.

White people cannot accept the real Martin Luther King because he was an angry Black man with a house full of guns who was incredibly threatening to white society.

That reality doesn’t center the white role. The reality we’ve come to accept is that the mere act of sitting down was enough to make white people realize something was wrong. The mere act of making speeches was enough to bring the white protagonists to redemption in their struggle to make equality happen.

And so we have The Magical Martin Luther King, our fictional character who speaks with a mystical eloquence to provide our white heroes the insight they need to complete their journey of salvation.

This MLK Day, like every other, we will hear people wax poetic and canonize the Magical Martin Luther King in tribute. It’s a lie. That canonization serves only one purpose: to devalue Blackness. It’s a way to ignore Black intelligence and Black agency.

The real Martin Luther King was complex. He was not a trope, he was a human, flawed, yes, yet a radical and powerful force of Black struggle. This Magical Martin Luther King that white people always talk about is a poor symbol of resistance.