Editor’s Letter

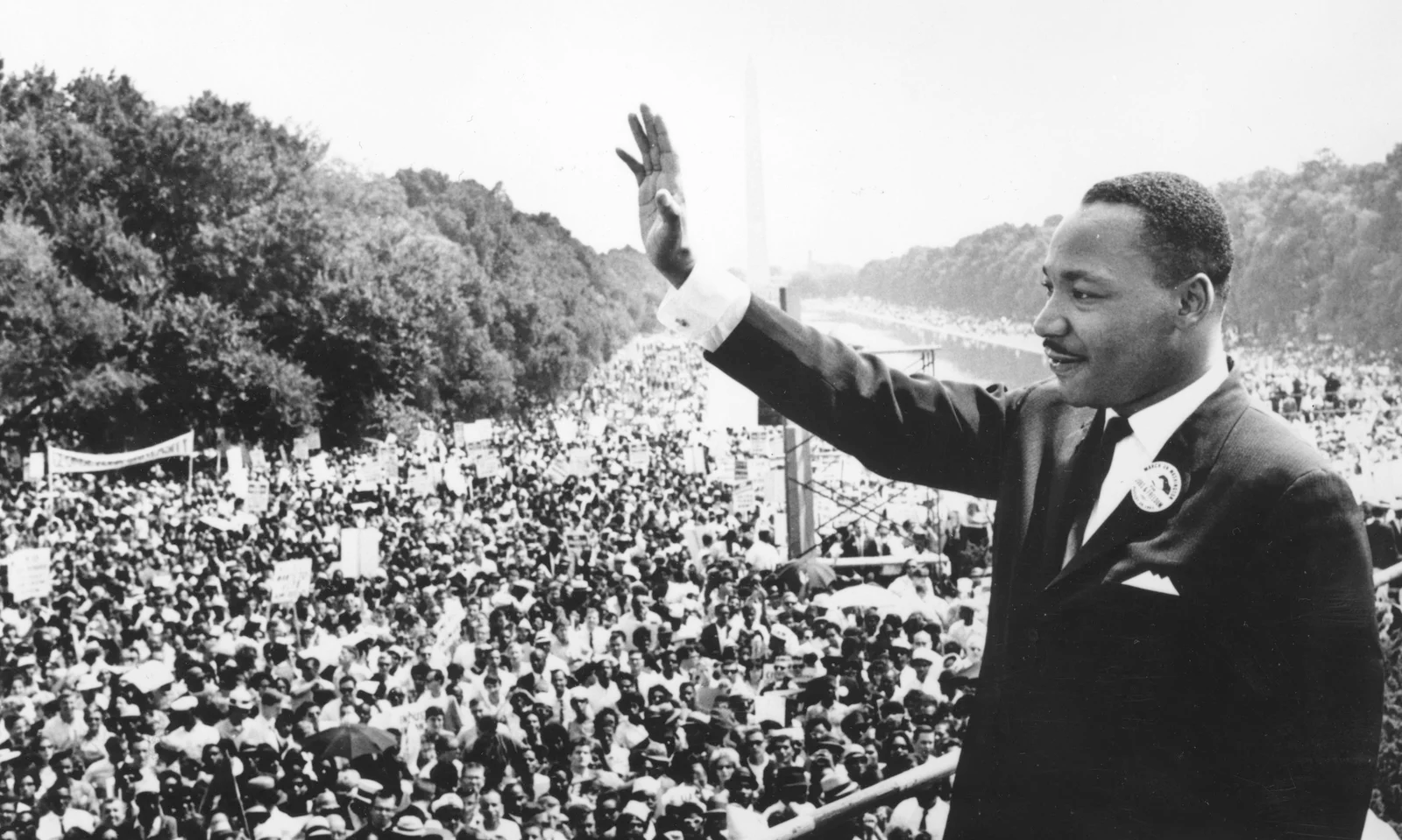

I hope everyone had an enjoyable and empowering Martin Luther King, Jr. holiday. If you haven’t read Terra Kestrel’s article “The Magical Martin Luther King is a Poor Symbol of Resistance,” drop everything and read it now. It was nice this year to see more authors like Terra highlighting the real Martin Luther King, and fewer candy-coated “I have a dream” quotes.

I read an article recently about the value of Black children attending all-Black schools from early childhood all the way through an HBCU. The author talked about centering Blackness, meeting Black people with a greater diversity of backgrounds and opinions, and having teachers who understood her—and how all of those advantages contributed to who she is today.

Her stance might seem antithetical to some of Dr. King’s goals, but we’re in a different place and time now and I'm sure she's right that there are some big advantages for a child and their self-confidence. I can’t speak to how they would be affected if/when they eventually moved to a more mixed (or majority white) workspace. I’m sure it would vary; I’d love to hear opinions. In any case, while I agreed with much of what the author stated, I still had mixed feelings about what is essentially segregated schooling, which I expressed.

I noted how having Black friends in school had a lot to do with my becoming the anti-racism advocate I am today, why I now have four Black “daughters” (former and current exchange students) and the broader importance of integration in eradicating racism. I don’t think the author agreed; she responded simply and pointedly that white people created racism and we need to fix it.

She’s right, of course. And I can completely understand a Black person wanting to avoid us white folks on a regular basis; honestly, I feel the same way some days! Unfortunately, if fixing racism were left solely up to white people living their best segregated lives, I doubt that anything would ever change. King himself, in his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” states, “We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.”

Quite simply, most people must be personally motivated to change, versus perceiving the change as having to give something up to someone about whom they know next to nothing. Being “fair” rarely seems sufficient, and that’s assuming that most white folks even understand how they’re not being fair. Sadly, it seems to be the way most people roll—and not just in response to racism.

The conversation got me thinking about the role of integration (or proximity, if you will) in easing racism. Certainly every person should have an equal opportunity to live, work, study, and play wherever they wish. Hopefully we can agree on that. However, does that proximity—or how much does that proximity—make a racist white student, neighbor, or coworker any less racist?

When I was a child during the Civil Rights Movement, Black folks and decent white folks were seemingly in agreement on the value of integration: it had to happen, and fast. We’ve all seen the iconic photos of poor little six-year-old Ruby Bridges breaking the school barrier amid a crowd of hostile white people. A lot of it was about Black people’s right to the same options, but it was also about the value of proximity in reducing otherness.

My own family was an immediate example of the value, albeit statistically insignificant. I remember my mother saying that she thought “Jewish people must have horns,” based on everything she she’d heard as a child, only to finally meet some and realize, “hey—they’re just ordinary people!” Likewise, my parents’ misconceptions about Black folks melted away when we moved from an all-white part of Wisconsin to the Chicago area. And it just seems so logical, doesn’t it—who wants to take advantage of their friends and neighbors?

Sadly though, there are also plenty of examples where the opposite seemed to hold true. My mind goes too often to the case of the three young Muslim graduate students in nearby Chapel Hill, North Carolina, who were much loved by all who knew them. They were harassed and eventually murdered by a neighbor. Plenty of Black folks have moved into their “dream home” out in the suburbs, only to be the victims of endless hate crimes. Most damning of all, enslavers had Black people all through their houses, raising their children, and never developed a shred of empathy.

So why does proximity seem to work for some and not others? To what extent does it help in the fight against racism? There are a couple of factors in effecting change, according to researchers in “Long-term reduction in implicit race bias: A prejudice habit-breaking intervention” (Journal of Experimental Social Psychology), that are relevant here.

The researchers split people into two groups: those with explicit vs. implicit biases, and focused on the latter. While they don’t say much about those with explicit biases, I believe that group would include people who are openly racist. Those with implicit biases are people who have essentially absorbed the racist views in our culture without being consciously aware of it—those who’d self-define as not racist, who’d say “not all white people,” who might even attend a George Floyd protest while simultaneously expressing or exhibiting racist views. They are, quite possibly, a lot of the “white moderates” Dr. King decries in his aforementioned letter.

The researchers say there are two critical aspects to reducing racism among those with implicit biases:

“First, people must be aware of their biases and, second, they must be concerned about the consequences of their biases before they will be motivated to exert effort to eliminate them.”

In other words, white people have to know they are racist on some level, and they have to care.

The first is why I am always pointing out that We White People Are All Racist. I’m sure some people find my words annoying, others find it painful, and still others reject it out of hand, but the simple fact is that it’s true: there is no way to have zero bias living in our culture.

This is not to say that we’re all confederate-flag-waving neo-Nazis at heart—far from it! If you find the idea of it repulsive, you’re probably a decent human being. But until we start questioning every single thing we think we know about people of another ethnicity, we can’t make much headway in resolving the problem. I’ve found that once you accept the notion, you discover yourself repeating things you’ve always said, only to rethink them. I have a friend who literally stopped herself mid-sentence at a dinner party to say, “Damn it—that’s so racist!” But it becomes less frequent if you do the work. Note that the researchers say losing our biases is a long road that requires reinforcement.

As for reasons to care, I do believe that a majority of us want to do the right thing, once we grasp the importance. The closer something hits to home, though, the more important it is: life is full of conflicts and we must prioritize. Aaaand, closer to home means proximity (remember proximity?!)—to your school, your job, your house, your heart.

If you make Black friends and earn their trust (i.e., not just that “one Black friend” so you can check it off the list like too many of us do), you’ll learn a lot. Some of it will hurt. If you’ve truly earned their trust, they will tell you things and sometimes call you out on things. But if you keep an open mind, they will be kind. You will do better. You’ll all move on. And the world will be a much better place.

Love one another.

Sherry Kappel

OHF Weekly Managing Editor

NEW THIS WEEK

The Magical Martin Luther King Is a Poor Symbol of Resistance

We sat on a park bench under the summer clouds.

Strangers, brought together by nothing more than the happenstance of being in the same park on the same evening and needing the same horizontal surface upon which to eat our picnic dinner.

We were three: myself, a woman of European descent, and a seven-year-cold Mexican boy who regaled us with stories of dinosaurs and warlocks who were really just boy witches.

“But I don’t know why they have a different name for boy witches because they’re really all just witches, and why do they need a different name if they all have the same powers?”

Why, indeed.

During a pause in our education, I asked about his mother. She was on the outskirts of the park because “she doesn’t think her English is good enough,” and despite being only seven, the literal metaphor of her not being invited to the table was not lost on him. He began talking about inequality and social justice with a subtlety that few adults manage.

“You don’t want to blame people because they are mostly just working and trying to make a living, and they don’t really want things to be unfair, but it’s hard to make things fair when you have to work and take care of your kids, but I always wonder why they don’t want to help more.”

Why, indeed.

That boy was smart, and listening to his grasp of race and class made me think that perhaps Latino children were given The Talk the way Black children were. I was just about to ask when I realized that I had lost the thread of conversation in thought, and was being asked a question.

“You know him, right?” he asked, obviously for the second time. The woman, too, was looking at me.

“I’m sorry, who?” I said.

“Martin Luther King,” he said. “He was great, I love him. You look like him.”

I told him that I really did not, but that I understood what he meant.

“He was really cool. He did a lot of good things.”

It was then that the woman spoke.

“Do you know why Martin Luther King was important?” she asked him, in an oddly aggressive voice.

The boy hesitated and did not answer.

“Do you know why?”

“I thi–” I started, but she cut me off.

“No, it’s important that you understand this,” she said, looking seriously at the boy.

Read the full article at OHF Weekly.

Final Thoughts