OHF Weekly writer, therapist, and corporate trainer Rebecca Hyman expounds upon three concepts from James Baldwin’s “A Letter to My Nephew,”—innocence, experience, and love—as applied to her life and how we all might benefit from the same.

Baldwin writes in his “Letter to My Nephew” about a peculiar characteristic of white people: they are blind. They live in a monochromatic world, attuned only to the experience and needs of other white people. In the way that snow blunts, distorts, and renders the physical landscape softer to the eyes, even as it makes the environment inhospitable to survival, so whiteness covers over its own violence, insisting the world it creates is beautiful, and benign.

Whiteness believes itself pure and light; its people good and worthy; its inventions useful; its philosophy moral. White people rest in the soft, downy pillow of their own superiority, believing their success the product of their own effort. It is the quality of not seeing whiteness, and not knowing the pain and violence being committed in its name, that Baldwin labels “innocence.”

Coddled and spoiled, white people are immature and quick to take offense if they are criticized. Attempts to remove the clouds from their eyes are unlikely to succeed. And yet, there is something in the experience of whiteness that is inherently dissatisfying. By staying in a self-referential space, white people lack the ability to connect with others, to grow up, to achieve psychological complexity. Their relationship to the external world, a mirror of their internal poverty, is flat.

Baldwin counsels his nephew to “accept with love” this white innocence. To truly love a white person is to ask them to see themselves “as they are.” For it is in the moment of gaining sight—of seeing one’s professed innocence as in actuality participation in a crime—that the white person has a chance to become fully human, engaging in the painful, hesitant, and uncertain work of undermining and overcoming white supremacy.

Innocence

Imagine waking one day, Baldwin says of this white person, “the sun shining and all the stars aflame.” The encounter with the truth of white violence is Biblical in its force: “the black man has functioned in the white man’s world as a fixed star, an immovable pillar: as he moves out of his place, heaven and earth are shaken to their foundations.”

When I read this passage, it sounds like white innocence is shattered at once—the old self is forever changed, in the way that Paul, who persecuted the Jews with zeal, is converted on the road to Damascus when he encounters the risen Christ. But when I look at my own history, I see a different awakening. A slow dawn, the light etching the horizon. The clouds first red, then pink, then white. Finally, a light so brazen I cannot face it without pain and an instinctive cowering before its force.

I am three. I climb onto my best friend’s lap and pull his dark face to mine and kiss him, because I love him and I want to know what kissing feels like. I don’t remember how he came to be my best friend, and I don’t remember why or when he disappeared from my life. I just know that when I think of my childhood playmates—all the other kids were white. Where did he go? Why didn’t I notice?

I am six. I learn why we live in this cream-colored stucco house with a red tile roof, on a street called Mediterranean Court, even though we are surrounded by woods, nowhere near a blue sea. My parents, who love cities, I am told moved here to protect me from race riots. I picture explosions, smoke. I hear sirens. No one tells me what caused the riots, or if they’re still happening.

I am nine. I’m watching The Jeffersons. They’re “Movin’ on Up,” the soundtrack tells me, as the camera pans up the side of an apartment building on the East Side. The laugh track cues every time someone thinks George Jefferson is a butler instead of an owner, or when he mistakenly attends a KKK meeting designed to return the building to its segregated past. The joke is on all the people—Black and white—who can’t get over their assumptions about race.

I am ten. My elementary school friends and I are anticipating Intermediate school. They tell me their parents don’t want them to go because there are race problems. I picture long hallways with dark green lockers and shiny tile floors smelling of bleach. I envision kids slamming each other up against the lockers; pulling each other’s hair; locked in a knot on the floor, punching each other in the head. I’m skinny, with glasses and braces. An easy mark in dodge ball. Will I learn how to fight?

I am twelve. I’m leaning against a railing, asking my father why adults don’t tell the truth. “What are you talking about?” he says. “Adults tell the truth.” Which one of us is right?

I am nineteen. I go to college at the University of Virginia. The students gather in tight groups of white or Black at the bus stops.

No one crosses over. I learn Father Joseph Brown, the professor who teaches African American literature, is regularly receiving death threats for doing so. I take the class.

I’m driving in the car with my college boyfriend. I tell him about Song of Solomon, the Toni Morrison novel I’ve just read, and Sweet Honey in the Rock, an all-women’s a cappella group. I start singing one of their spirituals. You want to be Black, he says. You want to live in Chocolate City.

I am twenty-one. I’m in the kitchen with my mother. I tell her about bell hooks, whose writings I have discovered. My mother is English. When I was a child I’d spin the globe, stopping at all the countries colored pink to mark their inclusion in the British Empire. I tell her about imperialist nostalgia, hooks’ term for the longing of white people for the culture of a people once they have been almost completely exterminated: how it’s safe, then, to exalt and mourn the loss. Why are you always so negative? she says. Why can’t you focus on something happy?

I am twenty-two. I decide I will escape the racist South. I flee North. Boston is where the abolitionists lived. In Boston I won’t have to deal with racism. I walk the city, cross the street separating Roxbury from Harvard Medical School. It’s everywhere; it’s just different from Virginia.

Experience

Years passed before I felt brave enough to enter organizing spaces that were almost exclusively Black and Brown. I’d had a number of cross-racial friendships and relationships by then. But my early racial schemas were so engraved in my consciousness that the love and intimacy I had received did little to alter my conviction I would be ignored, or greeted with contempt.

Instead, I was asked directly about my motives. I was told my language was off-putting, theoretical, and my insights weren’t needed. But no one, ever, asked me to leave. At first I was confused. These were my most valuable traits. If they didn’t want that from me, then what was I worth? What I discovered was that I was ordinary when white culture had taught me I should be special.

I cannot describe the relief of being able to name racism and not have the person I was talking to start to qualify, or evade, or explain it away. I think the most important thing that happened to me in those early years of organizing was that I got to exist in spaces where white supremacist culture wasn’t valued or expressed. It gave me a way to have distance from whiteness in the ways I had been trained to have distance from Blackness. I became able to see whiteness as an unacknowledged framework through which I organized my day, evaluated my personality, and envisioned my future. But when I viewed it as an artifact, a fabricated idea made flesh, I found room to imagine and inhabit ways of being that frustrated or refused its imperatives.

Whiteness splits our humanity and doles out the pieces to different racial groups, as if the entirety of the whole is too threatening to endure.

But what I didn’t yet understand, or have words for, was how whiteness was destroying my capacity to be fully human. I didn’t know yet what it was like to fall into the abyss of pain and let it break me open, and then not try to mend it. Whiteness splits our humanity and doles out the pieces to different racial groups as if the entirety of the whole is too threatening to endure. It links whiteness to rationality and transcendence of emotion. It ties Blackness to embodiment, joy, laughter, and suffering. It pretends white people can evade death through mastery of the body. And in doing so, it almost succeeds, rendering white people afraid of feeling, afraid of failing, afraid of change.

There’s this idea you lose your white racial innocence like you lose your virginity, suddenly and all at once. Ta-Nehisi Coates’s metaphor of the Dreamers is like this, too: it seems to imply there’s something, or someone, that will wake the Dreamers up. But in some ways I see that idea as too romantic. If only all it took was a one-night stand to rend forever the fabric of white racial innocence, never to be recovered. Or if one could have an experience traumatic enough to make it impossible to go back. What’s more chilling is that white racial violence occurs with such pervasive regularity that its normalization blunts its being registered by those most responsible to make it stop.

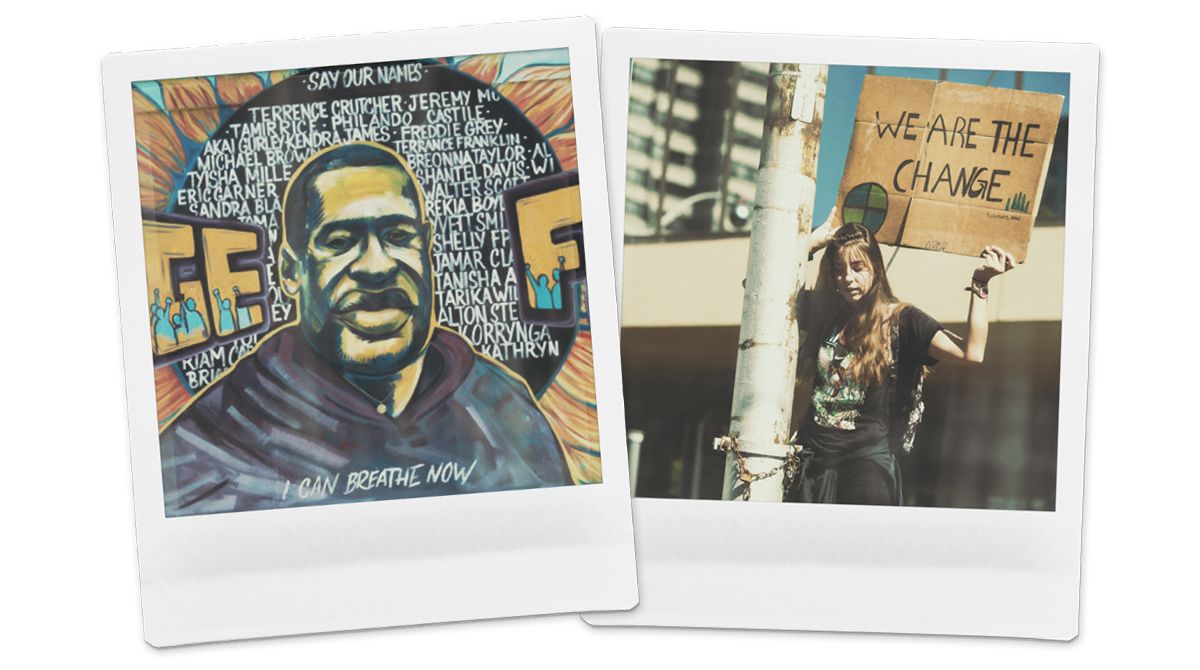

It’s possible that some white people did have that experience in the summer of 2020, with some saying the Floyd protests seemed to appear out of nowhere. I don’t know if that’s white innocence, again asking for a little more space and time to “process” this new information, to further delay accountability, or if it was truly a shock of awakening that will lead to sustained engagement in social change.

And yet to learn, absorb, and most importantly, to feel the complexity and interdependency of this network of oppression does not happen in a sudden, electric cataclysm. When I think about my life, which is a very ordinary white life, what I see is that I was never innocent. I was constantly being granted cover by other white people. And what was more insidious was that I could feel good about myself because at least I was reading the literature, learning the history—I could feel superior to my white friends who weren’t doing that, without ever really putting my neck out. I still have a thousand opportunities to lull myself back to sleep.

Love

Toward the close of The Fire Next Time, the book that includes Baldwin’s “Letter” and a second essay, “Down at the Cross” which recounts his choices to leave the church, avoid life on the streets, and lastly refuse to participate in the Nation of Islam, he devotes attention to the concept of freedom. All people surrender their power by believing in doctrine, or religion, or meaning systems, he notes, to protect themselves from the terror of existence. For Baldwin, it is the encounter with the brutality of existence that opens a space of radical, existential freedom: “It is the responsibility of free men to trust and to celebrate what is constant—birth, struggle, and death are constant—and so is love, though we may not always think so.” Love in this sense is not a pursuit of easy happiness, but instead, a chance to “earn death” by “daring and growth.”

White people are coached by other white people to maintain our innocence. We are told racism is happening in the distance—in other neighborhoods, other schools, other families. As if by being in white spaces we are free of the encounter with racism, instead of enacting it. The threat of naming white violence is racial exile. But the threat of maintaining white innocence is existential loneliness.

Maybe the first step towards Baldwin’s idea of freedom is for white people to look at themselves as vectors of white violence, and let that pain break them. And to witness the physiological, material, and emotional impact of white supremacy on the bodies, minds, hearts, and spirits of people who are labeled non-white. Once this deep recognition is no longer a concept, something to be analyzed and discussed, but instead something one feels in the body and in the heart, there is no going back.

But also, for white people to engage in radical acceptance of all the parts of the self, and all of the violence that has occurred in the name of escaping or “transcending” the pain and terror and love and fragility of being mortal, and ignorant, and suffering. Sometimes I think acknowledging white loneliness, and the longing for connection, is almost as forbidden as naming white violence. Sometimes I think writing is breaking the silence, a way of fighting, or dreaming our way out of the world as we know it. Sometimes words are a refuge, an ordering and re-ordering of ceaseless pain. Sometimes they’re a fishing line, cast into the air, searching for someone on the other end.

Images by Our Human Family.

Originally published in OHF Magazine, Issue 2.