In perhaps the only way I’ll claim similarity to James Baldwin, I started this story multiple times before deciding on a direction. I had the disadvantage of having months before it was due, allowing procrastination to disrupt my normal process. I read his letter to his nephew many times, hoping a theme would inspire me. Instead of inspiration, I just felt sadness reading Baldwin’s description of America and Harlem in particular to his nephew, also named James. The uncle and famous author was not kind in his description of America. He said, “Neither I nor time nor history will ever forgive them, that they have destroyed and are destroying hundreds of thousands of lives and do not know it and do not want to know it.”

Yet at the end of the letter, the uncle offered encouragement, pushing the nephew to persevere, reminding him of who he was and where he had come from. The suggestions as to how to accomplish that were few. James Baldwin, the uncle, himself left the country, spending most of his later years in France—though never leaving the movement in America. I wondered how the nephew James received the letter. Did he find motivation from his uncle’s words, or did he simply agree with his uncle’s assessment and simply try to survive? Did the namesake know from whence he came, and govern himself accordingly?

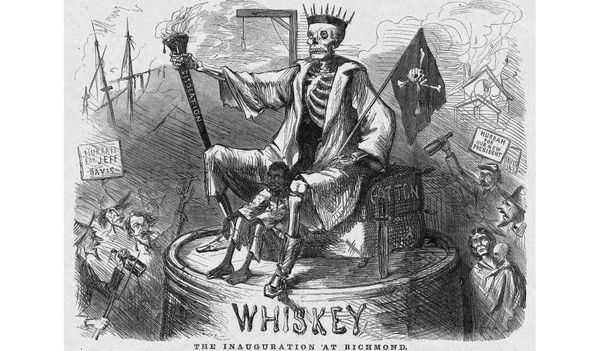

During the period in which I knew this article was to be written but nothing had been produced, I took a journey I’d been long planning but had been disrupted by COVID-19. My trip included some locations I’d written about previously but never personally seen: Lumpkin’s Slave Jail in Richmond, Virginia, Fort Moultrie in Charleston, South Carolina, the Slave Market in St. Augustine, Florida, Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello in Virginia. As an aside, I visited the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial, in Washington, D.C. What I’d heard about the monument had been negative, what I saw was inspiring. I’m reminded never to let someone else tell your history.

Baldwin and King marched alongside each other. It was King’s assassination that led Baldwin to seek refuge abroad. I believe he was tired of an America whose dream was not only deferred but denied to Black people, as Langston Hughes once wrote. When I stood at the bottom of the thirty-foot statue of King, I found the inspiration for this story that had been sorely lacking. I found the link between the description of America that seemingly never did the right thing and the hope Baldwin tried to instill in his nephew as if America would one day do better. Baldwin wrote:

“Great men have done great things here and will again and we can make America what America must become.”

Neither Baldwin nor King was under any illusion about America. They saw the good and the evil. King said, “The moral arc of the universe is long, but it bends towards justice.”

“We cannot be free until they are free.”

What King didn’t say is that the arc has fits and starts, sometimes going backward before getting back on track. It’s easy to get sidetracked during the bad times, sometimes becoming part of the problem and not the solution. Many white people blame Black people for the racial tensions that exist in society. If only Black people would change and do this or do that, their plight would be much better. Racism ended after the Civil War, or Jim Crow, or the Civil Rights Act or the Voting Rights Act, or some other arbitrary date after which racism never really ended.

The answer doesn’t lie in fixing Black people. James Baldwin knew this when he told his nephew, “We cannot be free until they are free.”

Reading that statement finally gave me the theme I wanted to write about. How do we “free” white people?

To be sure, all white people don’t need to be freed from anything. I’ll go as far as saying it can be hard out there being white and free as Baldwin meant it, given the degree of misinformation they’ve been given. When Baldwin told his nephew to “know from whence he came,” he didn’t address whether white people in America know from whence they came. In most cases they don’t. Not in the sense of not knowing what countries they originated from, but rather what happened once they got here, what were the laws and practices, what were the inherent advantages they had over Black, red, and brown people that have led to the economic disparity that exists today?

Without knowledge, how can we expect change? In fact, those white people I will call the unfree, will resist any attempt to even the playing field. They are the ones complaining about reverse discrimination and persecution of white people. The unfree only want the nation’s founders to be reflected positively in the history books; a group limited to land-owning white males is only to be shown as heroes, though most of them enslaved people.

In much of my historical writing, I paint a different view of history than the American Exceptionalism view you might find in a Texas schoolbook. It’s not because I hate white people, as some have claimed. It’s because I want all people, Black, white, and others, to be free, operating based on the facts as opposed to the fairy tale. If people have no understanding of why things are how they are, they might believe it was all merit or good fortune and that everyone had an equal opportunity to succeed. These same people dismiss the concept of voter suppression although evidence of the same is displayed on the news, in legislation, and in the courts on a regular basis.

We are in one of those times where the arc of the universe is stalled in its progress towards justice. The prevalent mood not only in America but others is nationalism. White supremacy is embraced by far too many. What used to be hidden behind hoods and sheets is now proudly embraced on social media. Their sense of reality is at best questionable: they are the ones who need to be freed.

James Baldwin suggested to his nephew there was a way forward. His was ultimately a message of hope and change, though a change has to occur on both sides.

I had (note the past tense) a good white friend who it actually hurt me to let go. His name was Earl and we met when we were managers of different sales forces for a telecommunications company. We attended many of the same meetings and often lunched together. Our children were approximately the same age, his just a little older. When I left the firm to start my own merchandising business, I hired his family as independent contractors to work events at arenas and stadiums and they became my top group. Whenever I had an event, they were my first call and they always got a prime location. We almost never talked about race, which is why learning some of his views was such a shock.

After several years of working together Earl and his family moved to Virginia. I got an opportunity to handle the merchandising at the Richmond Coliseum, which was about an hour from where they lived. I called Earl and worked it out for them to be the primary supplier of vendors for that site. After several more years, that contract ended and I didn’t see much of Earl, though I saw his daughter a couple of times a year at the US Open and the Super Bowl, events we worked at. Once I got a call that Earl was visiting relatives in Orlando, where I lived; he’d had a heart attack and was hospitalized. The number of people outside of my family I’d go see in the hospital is limited, but I rushed to see Earl. He recovered fully and we remained friends, our contact mostly on Facebook.

Around the 2008 presidential election, I posted something in support of a Black candidate and Earl replied. He invited me to read up on a different Black politician who shared his political views. Maybe Earl had always embraced racist views or had only recently been converted.

Somehow the subject turned to abortion. Earl said something to the effect that maybe it wasn’t such a bad idea for Black girls to get abortions as the crime rate would go down. I was stunned. I sent Earl a private message asking if that was what he intended to say? He doubled down and made himself quite clear as to his intentions. I am pro-choice and believe in a woman’s right to choose—but I would never advocate abortion as a policy for an ethnic group, as Earl did. That was our last conversation, although I do hear from his son from time to time who supports many of my views and comments.

When I write stories about race, I often have Earl in mind. I am never disappointed by the anonymous or unknown people who respond to me. Many agree with my writings, some suggest variations on whatever theme I espoused, others consider me racist, usually without explaining why. I’ve met many white people who were free long before I came along but perhaps got some additional insight from my forays into history. Others refuse to accept what I say no matter the documentation: it’s more than they’re willing to handle. I’ve had a few conversations, not nearly as many as I’d like, where we exchange ideas and come to a meeting of the minds. If I can help a few people to become “free” and they help a few more, we just might get something started.

James Baldwin suggested to his nephew there was a way forward. His was ultimately a message of hope and change, though a change has to occur on both sides. I would ask anyone still reading at this point to look for an opportunity to make a positive change in someone’s life. Is there someone out there you can help to be free? During the writing of this story, I’ve decided to reach out to my former friend Earl and see how he’s doing. I don’t know that we’ll solve the world’s problems but not communicating isn’t solving anything.

I’m still going to write about history and show America in a truthful light, which may not be what some want to hear. I will also reach out to people like Earl and at least try to share this truth. Maybe the good listener he used to be is in there somewhere? I can confidently communicate with Earl because I know from whence I came. Maybe the conversation doesn’t go well at all, but trying is better than never making the effort.

Originally published in OHF Magazine, Issue No. 2, The Baldwin Issue.

Member discussion