Editor’s Letter

In the past couple months I was near a couple of racist incidents involving Black women I know, and the incidents made me angry but also got me thinking about anger and how we deal with it.

The first was while shopping with Aisha, my Brazilian daughter, a former exchange student who’s now at Wellesley College on full scholarship but comes home to us for the breaks. She is very smart, as you might guess, with excellent English skills (she actually contributed an essay to Our Human Family’s Fieldnotes on Allyship when she was just seventeen!), and hopes to be a doctor someday. She’s also super kind, sweet, and bubbly.

Our whole family was shopping at a little boutique near my sister’s house in Illinois, each of us wandering around in different areas, and Aisha was bopping between us, looking at this and that. The store has a wide range of unique offerings, and I typically spend several hundred dollars there when we visit. I was already holding several shirts when my husband informed me that Aisha had left to sit outside and wait for us. It seemed a clerk was following her every step and glaring.

We have four Black Brazilian daughters we’ve gone various places with, and while I’ve seen hints of racism I hadn’t seen anything that overt. I think sometimes our white privilege extends to them, but in this case the woman saw her with us, referring to us as Mama and Dad, as she does, and it didn’t matter to the clerk.

We were furious. We dropped our potential purchases and walked out. Aisha, who has twenty-one years of experiencing racism, didn’t seem as upset as I was, but her sense was that the woman didn’t want her in the store.

We wrote a letter, and we won’t going be back.

The second incident was much scarier, although I wasn’t present. For some background, Earnest M. Lee was a Black folk art painter who grew up near Raleigh, North Carolina (where I live) and worked toward an art degree at St. Augustine’s University, an HBCU in town, until the grant program was pulled. He then moved to Florida where he died relatively young. His widow is friends with one of my besties and I also love folk art, so when she came to town to show his work at St. Augustine’s I had to check it out.

Choosing prints to purchase was difficult as Earnest had been very prolific, and many of them reflected sites in the Raleigh-Durham area, including families, farms, houses, forests, streams, and more. I narrowed my options down to a couple of prints and went up to pay, chatting with his wife Gloria, when I spotted a print that was unlike the others: a building and several Black folks engulfed in flames.

She said it was painted from an old article about the 1923 Black massacre in Rosewood, Florida. I assured her that I knew about Rosewood and asked her if she’d had any issues at showings around Florida. Just one, she said, her eyes turning dark and her voice trembling. Some men in one town told her “She’d better stop showing that painting” . . . and then that night, in 2023, someone burned a cross in the lawn of where she was staying!

The news is pocked with examples of racism, but I hadn’t heard of a cross burning any time recently—and I’ve never talked directly to a victim of something so heinous. It had obviously affected her deeply and she was still hurt and seething. What does one even say, besides “I’m so sorry”?

There’s always been a question of how, or if, even typically decent people understand empathy and others’ pain. Black people often ask why more white people can’t understand how they feel. We’ve all been angry! We’ve all felt pain!

If you’ve only read my essays here in OHF Weekly, you know I feel very strongly about human equity and equality. I will say that seeing racism directed at my daughter, and hearing from a victim like Gloria, really drove it home.

When I get angry, however, whether it’s about racism, misogyny, homophobia, or any other injustice, the response from many people has been, “I can’t listen when you talk that way.”

Why is that?

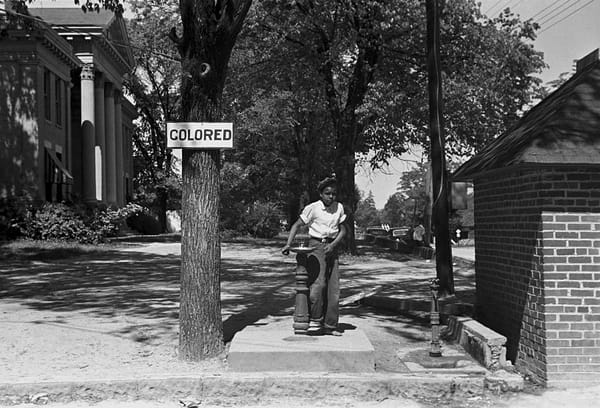

When a man gets mad, a white man, people stop and listen. The higher his perceived social standing, the more seriously we take his anger. He is passionate! He is earnest! He’s saying something important! Of course, men without the same social clout don’t get quite the same level of due, but particularly men of color. White people tend to have an unjustified fear of Black men in general, and when Black men are angry we tend to get scared. There are racist tropes about angry Black men–Black people, really–dating back to the first days of enslavement.

I know anyone who’s not a white man is typically considered much less influential when angry; I have observed this many times over the years, but studies such as this one from Harvard also confirm it. Black people’s anger is dismissed as “violent” or “uncivilized,” and irate women are considered “emotional” or “hormonal,” but the goal and the end result is the same—to dismiss the person and the reason they’re upset.

Think about the emotional constraints faced by Kamala Harris, Hillary Clinton, or Barack Obama when debating or campaigning. Think about how many Black men have been killed by police because the officers claim to have “feared for their lives.” Think about how feminists have been called “angry lesbians” for several decades. (And yes, the derogatory use of “lesbian” is a whole other level of misappropriated insult.) Think about the fact that there are so many Americans who are dismissive about what happened to Aisha, to Gloria, and to my response.

We all have the right to express our anger. We all deserve to be taken seriously when we are. And we all have the most basic right to express our feelings and perceptions—but then, that means others might have to acknowledge that the injustices that upset us have validity. Maybe Black people and women do have a right to equal pay . . . equal housing . . . bodily autonomy . . . not being followed in a store or facing a burning cross in the middle of the night.

Nobody knows this better than Black women, who are on the receiving end of the obvious double whammy that has arbitrarily placed them at the bottom of the social heap, making “angry Black women” such a common trope it almost sounds redundant. After racist incidents like the ones above, however, white people should all be angry for them instead of at them. Because make no mistake: the people committing those racist and sexist acts are often our friends, neighbors, and family.

Black women in my experience have been nicer and kinder than many people I know, despite the extra burden they carry. So let’s speak up when we hear people perpetuating well-worn tropes, and speak up even more loudly when we see racist incidents.

Sherry Kappel

OHF Weekly Managing Editor