True story: Several years ago, my mom was caught in rush hour traffic, paused on a railroad track, when the light ahead turned red. Without thinking, she threw her car into reverse and ran into the truck behind her. Fortunately, while she dented her bumper, she didn’t damage the truck. What the policemen told her, though? “Just blame them. No one is going to believe a white woman backed up into a truck full of Mexicans.” Full stop.

Say Hello to Officer Friendly

In our culture, we are raised from an early age to believe police are the good guys. In elementary school, “Officer Friendly” visits to tell us about his job, and he’s very reassuring. Our parents tell us the same thing: If you’re ever in trouble, look for the nearest person in a police uniform. There’s even a Muppet cop on Sesame Street. Sometimes there’s a policeman in the family or living just down the street.

As we go through life, chances are we encounter the police in a variety of settings—some of them good, some less so. Most of us get stopped once in awhile for a traffic violation, and sometimes the officer is nicer than others. I always get the ticket. My teary daughter always gets out of it. But it’s generally a quick and relatively polite exchange, either way.

On one occasion, my then boyfriend was detained while I was with him because he “looked like the suspect in a nearby crime.” He also looked to be a bit of a hippie, with bare feet, tattered jeans, and hair down his back. The guy they eventually arrested? Not so much. At all. On the positive side, my boyfriend was a PhD student; the police apologized.

The positive memories of Officer Friendly run deep. And of course, there’s Olivia Benson of Law & Order: Special Victim’s Unit.

On another occasion, I was sitting in my apartment at 5:00 pm in Pittsburgh when I heard a noise sounding suspiciously like gun shots. I ran outside—as did my neighbors—to discover the police racing through our backyards in pursuit of two teens who’d stolen a vehicle and crashed it nearby. My own backyard, in the middle of summer, where as often as not I’d be digging in the garden about that time. The teens were caught without incident. They were unarmed.

I’ve gotten to know quite a few policemen in their off time, as well. There was a police academy near my university where officers went to update their training periodically, and a lot of them lived in my dorm while they were in town. I ran the snack shop where they’d bring their beers and make bawdy jokes. They were offensive enough that some of the cops wouldn’t hang around with the others. We’d see them steal the cue sticks from the pool room so they’d always have one when they wanted. A girl in the sorority across the street was raped and picked one of those cops out of a lineup. I don’t know which one, and we never heard anything more.

Still, the positive memories of Officer Friendly run deep. And of course, there’s Olivia Benson of Law & Order: Special Victim’s Unit, who’s been our finest example for decades. When I’ve needed help, or observed anyone else needing help, I haven’t had a second thought about calling the police. I got locked out of my house in the middle of the night a couple of times in college and some super nice policemen helped me get back in. They could have been the ones from my dorm, or the ones who stopped my boyfriend. Hard to say. I was a young coed, and they were good to me.

Not Everyone’s Reality

Most people I know have similar views about the police. I mean, policemen are just people, some are better than others, but they have a difficult job and they keep our society safe. When we arrive home to find our door kicked in, we’re more than happy to let the police go in first. We are appreciative.

Of course, there’s one very big determining factor I’ve left out so far: I am a white woman, virtually all of the cops I mentioned were white, “most people I know” are white. In fact, white people usually skip that adjective and use none at all, which tends to make us think our views are universal—and that Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) experience life the same way.

BIPOC—and Black folks in particular—often respond differently to the police than white folks. In truth, even the most liberal, relatively well-informed white folks frequently fail to understand why Black folks can be so wary about the men and women in blue.

“Why didn’t she just pull over when the police turned on their lights?”

“Why didn’t they just do what the cops asked?”

“Why did he try to get away?”

“Why won’t they help the police catch the drug dealers?”

Why, why, why . . .

Black People’s Reality

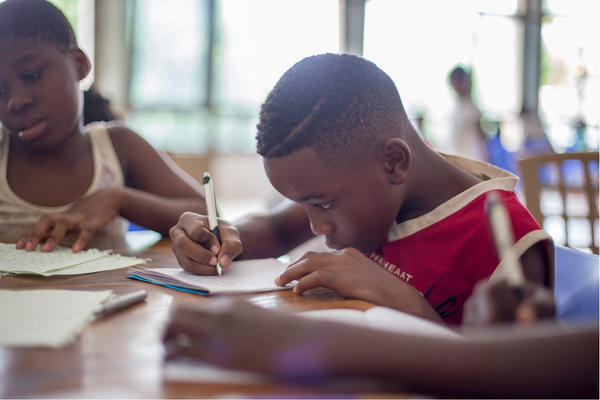

Almost half of all primary schools have resource officers, two-thirds of whom are sworn law officers with guns. More than four of five high schools have resource officers and the majority of those law officers are carrying guns (almost 71 percent). These aren’t the officer friendlies of my childhood who mostly popped in on occasion to convince you that guns and drugs are evil and encourage you to stay on the straight and narrow. These are serious people doing the serious full-time job of keeping school “safe”—which sometimes means keeping kids safe from kids.

My teacher husband’s current middle school, which is in an upscale (very white) neighborhood, has security, but the stories he tells are pretty benign compared to his previous schools where the kids were mostly BIPOC and free- or reduced lunch (i.e., impoverished). The policemen in those schools—often children’s first up-close and personal experience with police—are definitely not Officer Friendly. They have no interest in providing a positive first impression. They teach the teachers how to spot gang signs. Kids in these schools don’t get disciplined, they get arrested.

I can’t help but think of how many times my brother got yelled at for bringing a knife to school all those years ago. Not arrested. Not expelled. Rarely even detention. It was a different age and time, but again, he was white. If he’d been arrested, he might not have ended up a Chief Financial Officer. (See how that works?)

Then I think about the little Black girl who was arrested in Florida a couple years ago for having a temper tantrum, as kids do. A police officer handcuffed her! I Googled her and learned that the officer actually arrested two little Black girls in unrelated incidents. They were both six. Six! Some people will point out he got fired, but that won’t change the fact that these girls are traumatized forever. Their classmates are haunted, as well. Meanwhile, several incidents of police arresting little Black girls showed up in that same Google Search. Of course, little Black girls get tired and cranky just like little white girls—but only little Black girls get arrested.

These moments become more common as Black children grow. You might remember sixteen-year-old Taylor Bracey, the girl who was body slammed by a school resource officer onto concrete and knocked unconscious earlier this year. Or Dajerria Becton, a fifteen-year-old girl who was violently restrained in what has been called the Texas Pool Party Incident. Some don’t survive, like twelve-year-old Tamir Rice, who was gunned down by a policeman within two seconds of arrival for having a toy gun. Or fifteen-year-old Jordan Edwards, shot from behind in a car full of innocent teens.

In theory, these incidents can happen to white kids. The reality it that they happen far more often to Black kids, even though there are fewer of them. Some of this is due to the frequent “adultification” of Black children—seeing them as adults or having unrealistic expectations of them. Because so many white folks have an unfounded fear of Black people, studies show that we often misidentify them as older than they are.

For these reasons, many Black parents have what they call “the talk” with their children, in which they teach them best practices to lessen the likelihood of them losing their life during encounters with the police—quite the opposite of white parents telling their children to look for someone in a uniform.

As they grow, Black children are targeted more often and their interactions with the police become increasingly fraught, school for many Black kids is no longer the safe, nurturing environment my children knew, but rather a place that instills fear. This unequal treatment continues into adulthood, where Black people are almost twice as likely to be stopped while driving and more than twice as likely to be searched—even though cars driven by white people are more likely to yield contraband. And, per The Sentencing Project:

African Americans are more likely than white Americans to be arrested; once arrested, they are more likely to be convicted; and once convicted, and they are more likely to experience lengthy prison sentences. African-American adults are 5.9 times as likely to be incarcerated than whites and Hispanics are 3.1 times as likely. As of 2001, one of every three black boys born in that year could expect to go to prison in his lifetime, as could one of every six Latinos—compared to one of every seventeen white boys.

—The Sentencing Project

This quote doesn’t cover how a Black person arrested for the same crime as a white person, with the same background, is more likely to be convicted and get a longer sentence—even though they’re also more likely to be innocent, as the recent story about Yutico Briley illustrates. They’re two to three times more likely to be shot and killed by the police, even when unarmed, than their white counterparts.

Our “Reality” Guides Our Decisions

All too often, we think that our own reality is the only reality. There are many absolutes in this world, such as the earth being round, but lived experience is not one of those. (Oddly enough, “opinion” vs. “fact” has become confused of late. Those who believe the earth is flat think their “opinion” is fact, while believing that America isn’t racist is a “fact” because they haven’t experienced it directly.) People say we can’t really understand another person’s reality, but we can and must come a lot closer.

It should be obvious from our contrasting encounters with law enforcement that the reality for most white folks in America is very different than that of most Black folks. We’ve all seen children’s temper tantrums, but can you imagine your six-year-old white child being handcuffed and arrested for it? Imagine being violently thrown to the ground as a teenager doing nothing wrong; witnessing these events; seeing them on TV; reading about them in the news constantly. Imagine a third of the men you know being incarcerated.

Now go back to the questions I noted that white people often ask earlier this piece (“Why, why, why”), and see if you can answer them.

Postscript: Did George Floyd Get “Justice”?

Although Black and white realities diverge in our encounters with law enforcement, it is just one of many ways in which white privilege rears its ugly head. It is, however, a critical one to understand if we are to ever achieve racial equity, and George Floyd’s case is an instructive example.

Last year, George Floyd was murdered by police officer Derek Chauvin. In a rare moment of introspection prompted by video, white people were appalled and even joined the protests. Last month, Chauvin was found guilty. White people cheered. And last week, he was sentenced to over twenty-two years. White people cheered again: “Justice for George Floyd!”

The word I’ve heard most from my Black friends is “relief.” Not joy, not happiness, relief. If a jury could spend nine long minutes looking into the victim’s eyes while he was being murdered and still find the officer innocent, there would be no hope for any other case—or the integrity of white jurors in these cases. The other responses I’ve heard are, “We matter” and “We can breathe again.” They know that without the video, we probably wouldn’t have ever heard about George Floyd. They know George Floyd is just the tip of the iceberg. (It’s only the third time in the past five years that a Twin Cities police officer has been charged in the death of a civilian. The officer who killed Philando Castile was exonerated, while the one who shot Justine Damond–a white woman–was convicted.) Black people know police will kill twice as many unarmed Black men as white men this year and next year, just as they did last year if they are not held accountable.

White people have short memories. We feel good now. A lot of us have already crossed Black Lives Matter off our to-do list and feel the issue of racial injustice has been resolved. But it is not acceptable just to save the next George Floyd. Then the next George Floyd, and the one after him. Justice isn’t a one-off, and it shouldn’t require a fight, a protest, nine agonizing minutes of video, or even be a question. It should be a matter of applying the laws evenly to all people, every single time, in a country where we proudly claim “justice and liberty for all.”