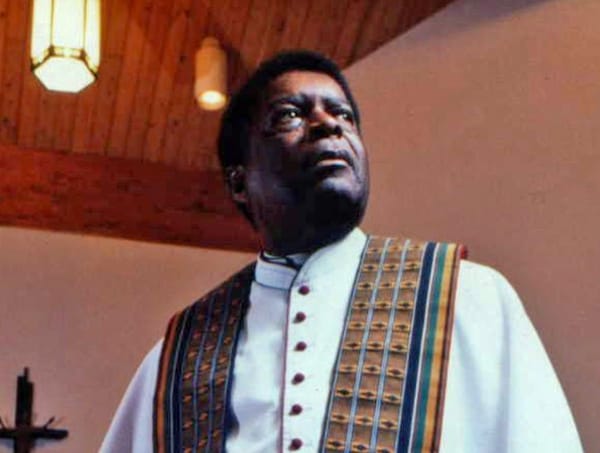

What makes some folks think it’s acceptable to treat Black people with contempt ranging from the veiled to the brazenly naked? And why do other folks treat us as the peers we are? You know, with genuine conviviality and all? After living in Black skin every day for well over five decades in a country where white is the default cultural standard for all that is meet and right, I’ve picked up a thing or two about what’s going on.

It’s Afrophobia. Yes, that’s a real thing.

The website Red-Network.eu gives an exhaustive definition well worth your reading, but for our purposes, I’ll define Afrophobia as any irrational fear and loathing of Black people and Black culture.

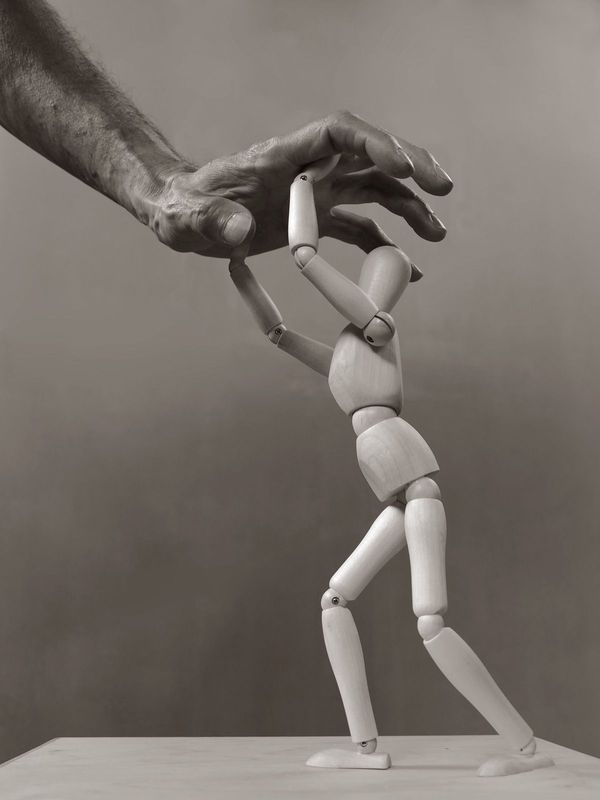

It manifests commonly in the misconception that Black people—except for the rare “good ones”—are lazy, uneducated, drug-addled ne’er-do-wells skilled in the dark arts of crime, violence, and self-destruction, and have a penchant for devouring our young—and yours, if given the opportunity. There’s also the ridiculous fear that Black people lie in wait to wreak retribution for our previous enslavement and centuries of past injustices, which is categorically untrue. Yet, even in 2022, some folks subscribe to this point of view. What we are waiting for and working towards is equal treatment under the law and in society without material and moral penalties because of the color of our skin.

Have you ever pulled your purse a little closer when a Black man enters the space? That’s Afrophobia. Have you ever crossed the street when you saw a Black person approaching you on the sidewalk? Afrophobia. Dismissed a Black woman as having nothing relevant to offer in a staff meeting? Afrophobia? Probably. Chances are there was some misogyny mixed in there, too. This brand of contempt is not beyond the realm of a blatant or latent sense of superiority. But that’s a topic for another day . . .

Despite people’s best efforts at hiding their disdain for Black people, our well-tuned Spidey-sense gets all tingly when we detect others’ fear of us in situations that should be regarded as benign for all intents and purposes. Especially, when dealing with folks one-on-one.

Of course, most reasonable people would sooner gouge out their eyes than admit to such behavior, let alone be accused of it. This explains feeble attempts at masking the behavior. But Black people can spot Afrophobia from fifty paces.

How can that be??

Black folks are adept at reading body language. Over these last 400+ years, our survival in America has relied heavily upon our ability to read white people’s intent. Not too long ago, the wrong move at the wrong time could get us killed. And today, the right move or no move at all can result in a lethal end for too many a Black life. Unfortunately, things haven’t changed all that much in that regard.

Despite flowery words (because, as my grandmother used to say, “People can make their mouths say anything”), silent but deafening indifference, and disingenuous glad-handing, body language rarely lies and we bear witness to all of it. James Baldwin once said in an interview, “I know you better than you know yourself.” And so do the majority of Black Americans.

Pro Tip: Sickly sweet intonation does not mask malevolence, indifference, or arms akimbo.

Conversely, why do some white people passionately take up the anti-racism and allyship mantle and engage us with authentic conviviality? I’m convinced, at some point, those folks learned that all people have more things in common that far outweigh the differences used to divide and conquer us. Sometimes those overlaps include a love of sports or some hobby. Maybe it’s finding out a co-worker of another ethnicity also lost a loved one to cancer. Maybe it’s a love of baking or Hip Hop. It could be anything. The point of mutual interest that then becomes the basis for conversation.

When people feel at ease around us it shows in their comportment and disposition. Anyone who’s been human longer than fifteen years instinctively knows when they are welcome in a space and when they are persona non grata, be it in the grocery store, the conference room, the classroom, at the bank, the salon, the gym—anywhere.

After that epiphany, they learn either by observation or direct questioning that the circumstances in which white folks live and those of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color are markedly different. They develop an awareness that opportunity and access are doled out with exacting inequity.

Case in point.

I have a friend (white) who has been actively advocating for Black surgeons nationwide since before “allyship” was a thing. We first met while doing seasonal work in the entertainment division at the Magic Kingdom in Florida. Neither of us can remember our first meeting, but I remember feeling that he was a good guy. Translation: I didn’t feel a trace of racial animus. We struck up a friendship, one rooted in mutual respect, care, and transparency—that has flourished over the last forty years.

When asked when he first noticed racial inequity, he told a story of growing up in a not-so-affluent part of town and his love of playing basketball. There were no other kids to play ball with in his neighborhood, so he played pick-up games with the kids from a nearby Black neighborhood. Over the years, they became friends, and by listening to his friends and observing, he learned of the disparity in resources and opportunities available to them at graduation. And that stuck with him.

So now my friend has made it his mission to provide Black kids interested in medicine who might not have the means access to mentors, professionals in the field, financial assistance, and more. All this to level the playing field for under-represented Black surgeons and as a means of paying it forward.

When I started this week’s letter, I wanted a provocative title. I found “Negrophobia” too “on the nose,” as they say, and instead opted for “Afrophobia,” which struck me initially as a comic fear of big hair. Unfortunately, as you now know, Afrophobia is a real thing and has been around for centuries. It’s more commonly known today as “anti-Black” racism, discrimination, or sentiment.

The good news is that people can shed their anti-Black racism when: they want to leave their racist beliefs behind, when they believe that change is possible, and when they know how to change. And love and empathy are two of the best tools for their transition. The trick is they have to choose to use them daily. Hourly. (Sometimes, by the minute.)

You may think me naïve for believing in concepts like hope, redemption, forgiveness, and love. You might be right, but naïveté presumes a lack of experience, wisdom, or judgment. I may lack one of those traits, but I assure you, it’s no more than one. I’d prefer to help people discover the good in themselves and others than cede one inch to cynicism and pave the way for hatred.

The human experience transcends gender, age, physicality, mental capacity, and certainly the lies of race and racism. We are more alike than we are unalike. Note that I did not say, “we are the same.” The lived experiences of Black people differ from those of white people, which differ from those of Indigenous people, which differ from those of People of Color. But none differs to the point it ceases to be human. Our shared humanity exists in the overlap of those experiences. That’s not to imply that if one group does or experiences something unique to their culture they no longer cease to be human. That’s merely an opportunity for others to understand and grow.

If you’re intrigued by this letter, great! Check out more of our articles, and drop us a line. If this letter makes sense to you and you agree with it, great! Share it and talk about it with friends. Because as Toni Morrison said, “. . . remember that your real job is that if you are free, you need to free somebody else. If you have some power, then your job is to empower somebody else. This is not just a grab-bag candy game.”

Love one another.

Clay Rivers

OHF Weekly, Editor-in-Chief