EQUAL PEOPLE 2022 SHORT STORY WRITING CONTEST CO-WINNER

Content Warning: The following story contains graphic violence, murder, and strong racist language.

I

Louisiana, 1868.

Saint Bernard Parish lay in ruins. The backwoods were littered with deceased freedmen. Trees wore the bloody fruit of people who had been enslaved less than a decade ago. Arthur Delacroix’s chest heaved in gratification as he thought of how many niggers he sent to hell this night. His hands were stained with the blood of the freedmen he and a gang of white men had massacred.

“These niggers won’t be voting for that bastard Grant. White folks run this shit, not that traitor to his people. Republican scum won’t beat Seymour. 1868 is the year white folks win back the South.”

He still clutched voter registration papers he had removed from dead freedmen. He thought, “they won’t be voting,” as he threw the pieces in his fireplace.

Only ten years ago, the Delacroix Plantation had been a decent producer of sugar cane and the home of twelve enslaved people. But unfortunately, Lincoln freed them when the war came, and he lost everything.

He still raised a tiny bit of cane, but now he hired poor white folks to harvest his cane since he couldn’t own darkies anymore. He wasn’t about to pay folks he once owned any hard-earned money.

Delacroix went to the water basin and washed the blood from his fingers and hands. The mirror reflected a face splattered with dried blood and small bits of flesh. To him, it looked like a good night’s work, but to any rational human being, it was horror.

Art was a big man. He was built like an oak tree and had arms the size of tree stumps. A vast brown beard with gray streaks stretched across his broad face. His eyes looked wild and were small for his hog-sized head. He was of average height, but his hatred of all things non-white made up for his lack of stature.

He removed his blood-stained clothes and put them in a burlap sack he was carrying. Tomorrow they would go on the fire. He felt good as he crawled into bed next to his wife. It was a good night’s work, and the Negroes left alive knew they better not show their dark faces at a poll this election day. He drifted off to sleep with gratification coursing through his body. He felt no empathy for the people he’d slaughtered.

II

Art woke up in a pool of sweat. His heart raced, and his head felt like a herd of elephants was stampeding across his brain. He rolled off the bed and went to the mirror. His bloodshot eyes surveyed his face, its color matched that of dingy cotton. He was dizzy and could barely stand.

He stumbled down the stairs to the kitchen. Through blurry vision, he barely recognized the coffee container in the cupboard. He put some water in the coffee pot, brewed two cups of coffee, and waited.

He downed the coffee. His wife, Mabel, came into the kitchen.

“Art, what’s wrong?”

“I don't know,” he stammered. “It’s my head. Maybe one of the darkies hit me, and I didn’t realize it. It’s horrible. I don’t know what to do.”

Mabel stared at him.

“Can you saddle George and go on to Doc Reed’s?”

“I think I can.”

“Can you pick me up a bag of flour on your way back?”

“I don’t see why not.”

Art saddled his horse and made the two-mile trip to Doc’s.

He arrived at the doctor’s house and walked up the short path. He knocked and waited. The door opened, and a young man was standing there.

“Who are you?” Art asked.

“Gabe, sir. And you are?”

“Arthur Delacroix. Where’s Doc Reed?”

“He had family business in Slidell, so he left me in charge. I attend Tulane Medical School. Doc Reed was kind enough to allow me to shadow him as part of my medical residency. So I’m capable of helping you if you need medical attention.”

Gabe was well dressed in a three-piece blue suit with a tie. His hair was well-groomed, and his ivory face was clean-shaven. He looked harmless enough, so Art told him about his headache.

“I see. Well, come on in and let me have a look at you, Mr. Delacroix.”

The medical student asked Art a few questions about his condition.

“I think I have something to knock that headache right out.”

“Really,” Art said, startled by Gabe’s confidence.

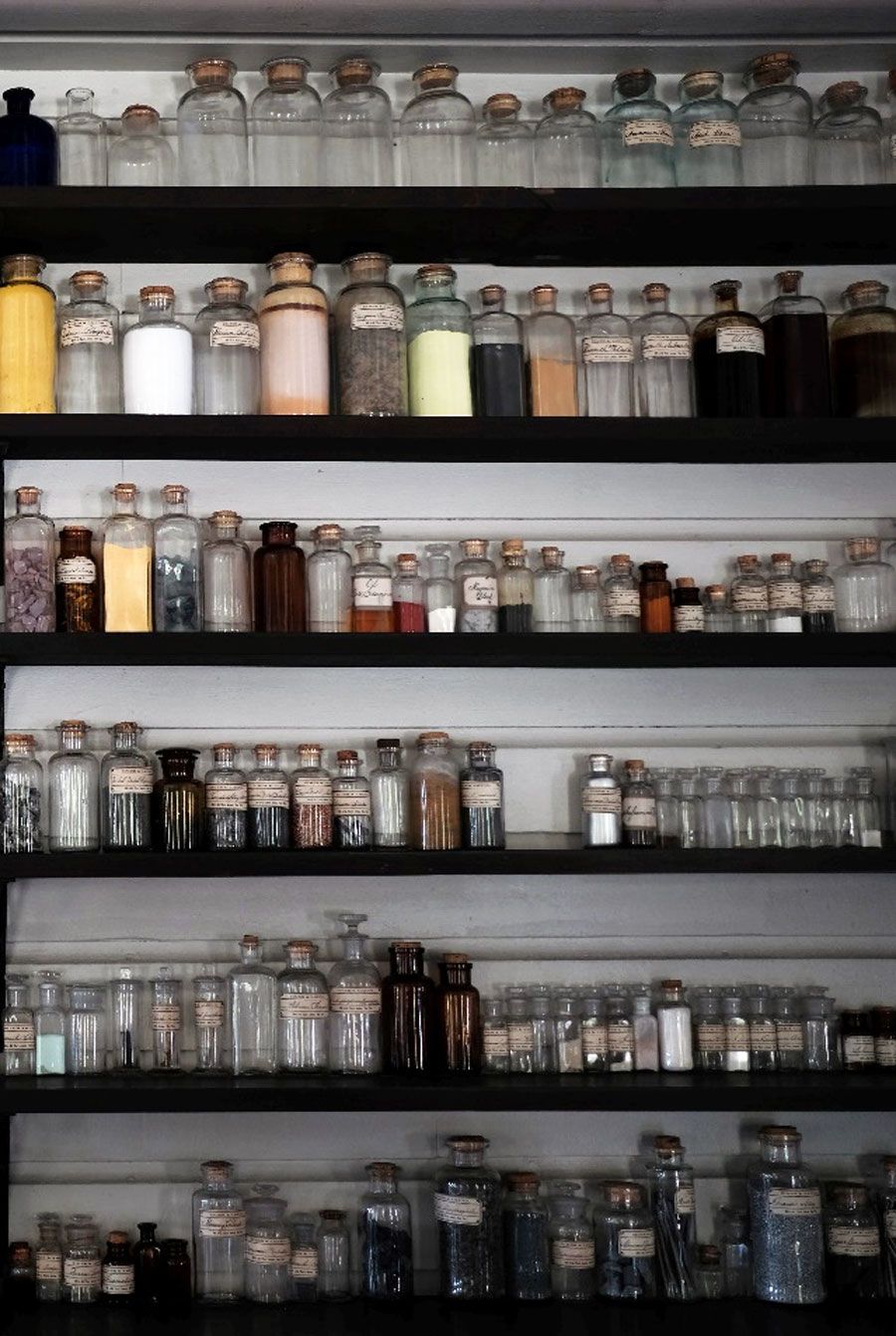

Gabe reached under the table and laid a brown leather medical bag, altered with deep wrinkles, on the table. The handle was cracked from age, and the clasp was tarnished from wear.

The young hand that rummaged through the weathered bag looked out of place.

He plucked a clear glass bottle filled with tiny round disks from the bag. “These are headache pills or wafers. Take two of these, and your headache will be gone in a few minutes.”

“Really?” Art said in disbelief.

“Yes.” Gabe poured his patient a glass of water.

“Here ya go.”

Art took the pills, and the medical student led him to a chair by the fireplace.

“Sit here for a moment so I can observe your reaction.”

For the first five minutes after taking the pills, Art felt no different.

“Hey Gabe, my headache is getting better. I am starting to feel like myself again. Man, what are those pills? They’re a miracle.”

“A new treatment for headaches and some other bodily pains.”

“Thanks so much.”

“You’re welcome, sir. I hope the rest of your day is peaceful.”

Art shook Gabe’s hand and walked out to his horse.

Gabe watched Art as he trotted off down the road. A smile crept across his face as he closed the door.

III

Art was amazed at how good the pills that Gabe gave him made his head feel. Finally, he arrived at Mack’s Dry Goods in the mid-afternoon. He tied up his horse and walked in.

“Hey, Art,” said Mack. “We put the fear of God in those niggers last night, didn’t we? Ain’t a one been in here to even buy a stick of licorice. I hear some might still be hidin’.”

“Let them hide. I don’t give daaaaaa—”

Suddenly his voice trailed off into a howl that could chase away a ghost.

“No, daddy! Nooo! What dem crackers did to you? Come back, daddy! Come on, we gotta go home!”

It was as if Art was in the body of a little black girl. He could see the little brown hands covered in her father’s blood. The child’s pain and despair coursed through every fiber of his being.

He screamed and began sobbing like a newborn baby. Tears ran down his hoary cheeks.

“I’ll hold your head, daddy, till help comes. I ain’t going to leave you. You all mom and I got.”

Art felt every morsel of her despair. A little black girl and her mom were left to fend for themselves. A tsunami of emotion crashed over his body. He felt like he was underwater and couldn’t breathe.

Mack shook him and yelled, “Art, Art! What the hell matter with you? Man, what the hell was that?”

“I don't know,” Art said as tears streamed down his cheeks.

He slowly stumbled to his feet. A visceral tremor coursed through his body. While a deep unimaginable fear was burning in his chest, he looked at Mack’s white face with a loathing he had never felt before.

“Get away from me,” he screamed. He pushed the shopkeeper out of the way and made his way clumsily to his horse.

Delacroix galloped at full speed like a demon was chasing him. His sweat soaked circles in the armpits of his thick cotton shirt. His skin was moist and pale.

Suddenly, thick darkness engulfed him. The trees around him seem to close him in. It wasn’t his horse he was riding; it was a horse he had never seen before. Then, behind him, he heard voices yelling, “Get that nigger!”

“He ain’t going to tell us he voting for Grant and get away with it. Come back here, boy. We just wanna talk!”

Delacroix knew what that meant. They were going to shoot or hang his ass and leave him dead. He knew because he had done it before. However, this time was different. He was running to escape. Like earlier in Mack’s store, he was living in this black man’s skin. He heard the man’s thoughts about his love for his wife and daughter, how he hoped and longed to see them again. The crippling fear this man felt was palpable.

Every heartbeat was a thunderclap in his chest. Every ragged breath felt like his last. Art was running for his life as he saw what seemed to be his own black hands gripping the worn leather reins. As a white man, Art had never felt such utter hopelessness. He felt the grip of the white man’s curse upon his life. It was like icy fingers dragging across his back.

Being powerless felt foreign to Art because he’d always had the power to terrorize at will as a white man. Now he felt the horrors of being black in post-Civil War America, and there was nothing he could do about it.

A shot rang out. A bullet pierced Art's back and exploded through his chest. The pain spread through his body like electric shocks. The hot metal seared his flesh as it entered and exited his body. He fell to the ground and waited for his death. Over him stood Captain Veillon.

Art saw the faces of the freedman’s wife and daughter in his head. The loss of the most important things in this man’s life weighed on him like dirt in a grave.

Cap pulled the trigger.

Art woke up on the side of the road. His horse was long gone and the sun began its dip into the horizon. The weight of empathy hung on his shoulders and the darkness of his own heart frightened him.

Vision after vision came to him. Several white people gazed after him as he stumbled down the road. Some called his name, but he could only scream at them through slobbering lips.

“Why do we kill Negroes like bugs under our feet?”

“We owned and beat them without mercy!”

He saw Cap Veillon riding towards him, yelling at him to stop.

“Art, what you doing yelling this shit in the road?”

He pulled Veillon from his horse and threw him to the ground.

“We sold their kids and broke up families. Last night we murdered fathers, sons, and mothers. I’ve felt it, Cap. It’s like knives in my heart. This is how black people feel every day. It’s wrong, Veillon.”

Art felt he was outside his body. He heard what he was saying, and he could hardly believe it was him. But he couldn’t stop all the emotion that poured from him.

Cap pushed him off and stood up.

“What’s going on with you, Art?” he yelled. “What, you a nigger lover now?”

He felt the sting of those words. So black folks aren’t worthy of love, he thought.

He screamed at the old cracker and punched him.

He ran until he found a safe place to think.

What the hell happened to him? It all began that morning after he saw Gabe. Maybe he had answers, so Art started walking back to Doc Reed’s.

IV

After about a mile of walking through the woods, he felt a presence following him. He turned but saw nothing but darkness.

A hand fell on his shoulder before he could turn around. The forest turned bright, and heat moved throughout his body.

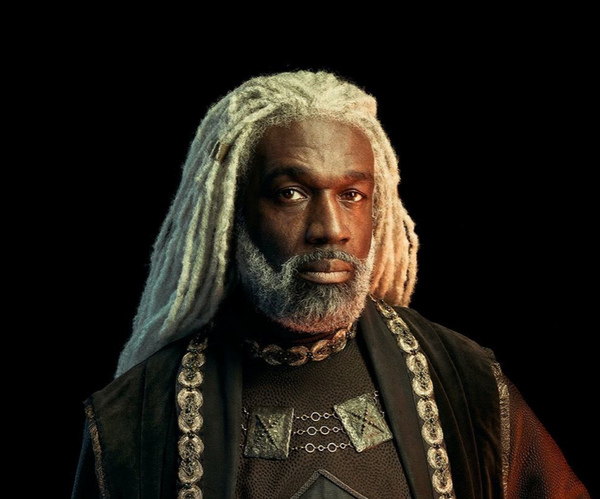

There was a flash, and suddenly he was in a church. He looked up at the pulpit, and a black man was standing there.

“Where am I? Who are you?” Art asked.

The black man walked from behind the pulpit and placed the same old, tattered doctor’s bag on the front pew.

“It can’t be,” Art said. What did you do with Gabe?”

The Negro looked at him strangely.

“I am Gabe.”

“Bullshit, that’s not possible.”

“Really, Art? You can say that after you’ve lived the death and horror of an entire parish of black people? I would say about anything is possible at this point.”

“Yea, I admit some strange stuff has happened to me that I can’t explain, but people can’t change shape.”

In an instant, the black man became white Gabe.

Art gasped in disbelief as Gabe became black again.

“This is my proper form, Art. I am the Archangel Gabriel.”

The room shook like an earthquake.

Art gasped, and his heart leaped into his throat.

“What did you do to me?” he stuttered.

“I wanted you to feel every emotion running through the people you despised so much and killed freely. I gave you a glimpse into what it means to have brown skin in America.”

Art stalked around the church crying and screaming for the emotional pain to stop.

“I still feel the loss and hopelessness of the black people in Saint Bernard,” he said between sobs. “It’s like I am living like them. I am a piece of shit, and I realize that now. Before that, I didn’t carry these feelings in my spirit.”

Art fell to his knees before the angel.

“I understand they are just like me, not animals or property but human beings who were done wrong by my own kind, and I was a leader in the carnage.”

“You, sir, were and are the worse type of racist. Black people were trash to you and could easily be disposed of. Yet, you welded your power over them with relish.”

“I understand I’ve been wrong all these years. I despise myself for what I am.”

“Well, Art, truthfully, if it was up to me, I’d cast you into the pit of hell and be done with you. But as I’ve been instructed, we will give you a chance to right the wrongs of your life as a slaver and a murderer.”

Art looked at the Archangel before him. “I will begin by taking care of that wife and daughter. They are alone now and will need protection and support.”

“We shall see, Arthur Delacroix, but hell will be your home for eternity if you don’t.”

A light flashed, and Art was on his doorstep. He didn’t know how to change without risk to his life, but he owed it to the black folks he’d terrorized since he was a boy.

But how he thought. How?

Author’s Note: I must acknowledge the book The 1868 St. Bernard Parish Massacre, written by C. Dier. My story is historical fiction but a man named Veillion did exist in 1868 in St. Bernard Parish. I read the book to get an idea of the massacre.

Photos by Chelms Varthoumlien on Unsplash