EQUAL PEOPLE 2022 SHORT STORY WRITING CONTEST CO-WINNER

She scans the list of the personal details of her Syrian students. The course will be starting in a few months and this will be her first time teaching English to Arabic-only students.

Five couples with an age difference of around ten years between the husbands and wives. Number of children, an average of two to three. Low level of education. So low for some, she envisions literacy issues.

She notes the ages and stops. Female, twenty-two, married with three children, husband thirty-three. Their oldest child, seven. She calculates. Fifteen years old when she gave birth. She identifies another two young brides. She sickens. She cannot do this job. Child brides shackled by the men who deflowered them and fathered their children. Can she intrude on their privacy by entering their living rooms via a laptop? Does she want to observe an intimacy based on something so foreign and repulsive to her?

Yes, they are in need, and yes, she can provide them with the key to a culture so different from theirs, the entry into which is required to integrate into Irish society and thrive.

She has her issues though with Muslim men and how they treat women. And now this. She’ll have to think it over and hopes there are other teaching opportunities open to her.

Her eyes wander and halt at the little plastic bottle on the table in front of her, light brown and boring, filled to the brim with colourful little pills. It arrived one day in a small parcel with no sender but a card enclosed with the words:

Empathy Pills: Take one if need be and see the world upside down, the other way around and experience enlightenment.

She had laughed and wondered at the cleverness of the jest. She knew immediately who had sent it. This was not the first time her white witch girlfriend had sent her a crazy concoction of sorts. Though she had never dared to try any out, she was now in the mood. Any distraction would do to lift her spirits.

She looks at the list of names again and with a sense of defiance grabs and opens the bottle. Inhaling the escaping powdery air, non-toxic and sweet, she smiles. Uttering a loud “Simsalabim,” like a child, she spreads the ten or so colourful beads onto the table in front of her. She closes her eyes, and fingering several pills, she chooses one, lilac, pops it into her mouth, and swallows it. She refills the bottle, slips it into her pocket, and waits, surprised by her silliness.

What if the pill makes her sick? What if . . . she feels a tingling sensation in her feet, in her fingers, a slight headiness; she stands up and suddenly her body begins to tremble from head to toe. She feels her organs shake inside her and is reminded of the time she experienced a small earthquake. The vibrations running through her body were strong enough, she remembers, to stop her in her tracks as she ran to her daughter’s room to see if she was safe.

It’ll soon be over, she reassures herself as perspiration gathers in the folds of her body. All of a sudden, she is swirling in a vortex of air around and around, up and down, until a few seconds later she lands gently on her feet. Dizzy but relieved to find herself in one piece she looks around. She is in a dark hallway. It is hot and dank. So, this is how Alice in Wonderland must have felt, she thinks.

She hears Arabic music coming from behind a doorway. A shabby blue curtain is blocking the entrance. She hears laughter; suddenly the curtain is pulled back and a young woman, at first surprised, smiles shyly at her and beckons her to come in.

Where is she? How did she get here? Who is this woman with the colourful scarf framing her face? It all makes no sense.

Somehow though she is not afraid. As strange as this transition into another world has been, the friendliness of the slender and pretty young woman waiting expectantly at the doorway reassures her. She walks up to her and follows her into the room. Her senses take in the smell of strange spices and the dishes of foreign food decorating the table in the corner of the room. Seated around the table are three children and a man, the head of the family she presumes. Mouths open, three pairs of wide eyes, dark and solemn stare at her. The man stands up, pulls up a chair, and offers her a place at the table.

The silence is broken with the hostess offering her some of the sweetmeats. The young woman glows with pride as she hears how delicious her food is and answers the question enquiring whether she had made them herself with a flattered, “yes.”

By now the children have overcome their shyness and are eyeing her with curiosity and fits of giggling. Their father shushes them away from the table somewhat gruffly and then orders his wife to bring some tea which she rushes off to prepare. At least this is what she presumes he does. To her, Arabic always sounds so guttural and bossy. She watches the woman heat water in a saucepan on a stove on the other side of the room, the darkest part. She makes out a sink, a few cupboards, and a small fridge.

“Are you from UN?” The husband surprises her in his broken English and noting her consternation adds, “Are you here for questioning me and family?”

And then it dawns on her. She remembers the list. Her new students are Syrian refugees who fled to Lebanon to escape the war in Syria and have been living there with their families for some years. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and the Irish government have selected them to resettle in Ireland. They are part of a resettlement programme whereby Ireland committed itself to take in a fixed number of families. And she as their English teacher in Ireland is part of the programme. The families haven’t been informed yet.

“No,” she says, “I’m not from the UN and I am not here to question you and tell you if you can go to live in Ireland or not.” Now, it is his turn to look bemused. He can’t hide his disappointment.

“Who are you?” he wants to know; prepared for this question she answers that she is an English teacher sent by the Irish Government to see what English language needs the Syrian families have before they are interviewed by the UN. Taking out her mobile phone she searches for the English-Arabic translator and translates what she has said into Arabic for him. All made up, of course. He listens.

Relieved, he picks up his mobile and, speaking Arabic into it, invites her to listen to the English translation.

“We welcome you with our hearts and are grateful you are taking your time to interrogate us.”

The English teacher smiles, amused at the clumsy translation. By now the man’s wife has returned with the tea. She likes its cinnamon taste and says so through the translator. This pleases the couple.

She is touched by their generosity and willingness to share what little they have. Though poor, their room is very tidy, the threadbare carpets on the floor and walls are clean. As are the chairs and tassel cushions.

The English teacher asks them their names after telling them hers, Deidre, which in unison they repeat, “Dee-a-dra”. He says his name is Ahmad and introduces his wife, Amira, his two daughters, Fatima and Lilian, and his son, Mahmoud. Deidre notes the pride Ahmad shows for each of his family members, particularly for Amira, his wife.

And now to their ages. “I’m forty-nine,” Deidre begins, “And you, Ahmad? How old are you?”

“Thirty-three,” he replies.

“And you, Amira?” she asks.

She turns to her husband who whispers “Twenty-two.”

“Twenty-two,” Amira repeats shyly.

“And how old is Mahmoud?” Deidre continues.

“Seven,” the answer.

“Fatima?”

“Six.”

“And Lilian?”

“Three.”

Deidre is back to the beginning. A downward spiralling of emotions. She looks at Amira. “So you were fifteen when you had Mahmoud?” She is close to tears at the thought of this young girl having a child at so early an age. Robbed of her childhood she was. She knows Amira won’t understand the question and has already begun typing it into her mobile. The young woman listens to the translation and nods.

She continues by asking Amira how old she was when she married Ahmad. “Fourteen,” he answers for her. Deidre looks at him. She isn’t sure if he can imagine what she is thinking. An intelligent person who loves his family, how on earth can he justify marrying and impregnating such a young girl?

The English teacher goes on the offensive; not caring if by doing so she is overstepping social etiquette.

“Fatima is very pretty,” she says looking across at the little girl sitting on the floor with her siblings watching a cartoon on a tiny TV. “You said she’s six years old. So, if I’m correct, in about eight years she will be fourteen and you can marry her off to an older man. She’ll be the same age then as your wife was when you married her.”

Confused, he stares at her for a few seconds, and then, realising what she has said, he takes up his mobile and begins solemnly typing into it with a fervour that surprises her. She wonders what he’ll come up with. He’ll probably tell her it’s not her business to ask him at what age he’ll marry his daughters off.

“Marrying a child off so young is against human rights and should never happen. My daughters will go to university and have jobs if they want before they marry. They will be free to choose.”

She is taken aback. “But . . . ” she begins and then starts typing into her mobile, “I thought it was common in your culture for older men to marry young girls.” He listens closely to the Arabic translation.

And likewise, she listens to his explanation translated into English.

“True, but that was in former times. Before the war in Syria, it was forbidden for men to marry girls under seventeen. It still sometimes happened, though, especially in the countryside.”

She still hasn’t an answer as to why he and other Syrian men are again marrying very young girls.

He is busy typing. She knows he’s going to give her the answer. No need for her to ask. She waits and takes in more of her surroundings, noticing that under the window with its cracked pane, two mattresses stacked on top of each other are piled with pillows and folded blankets. So, it’s only the one room they share, she muses. She looks back at Ahmad who is observing her scrutiny of the room. “We have one toilet and five families,” he says before he switches on the translator.

“The war in Syria ended this progress. Life for young girls of marriageable age is dangerous in this war situation. Families are displaced and living as refugees in different countries like Lebanon where Syrian people are vulnerable. Parents who are not only impoverished are desperate to protect their daughters from sexual harassment and rape and see no other solution than to marry them off as soon as possible.”

He types and she listens.

“And this is why Amira’s parents approached me and asked if I would marry their lovely daughter.” He looks fondly over to his wife who laughs, not quite sure why her husband is looking at her like this in front of the visitor.

The English teacher feels the love and respect they have for one another.

“Ah. Okay,” she says. Touched, she can think of nothing further to say.

She can follow Ahmad’s explanation and, in his case, accept it, though she will never condone the practice. She knows not all young girls have happy and safe marriages. She sighs. War and its consequences cause so much misery and upheaval.

Without translating, Ahmad speaks directly to her.

“I want to go to Ireland with family. I want happiness for them. Amira will learn in school again and she will drive car. I will work and she can drive children to school. Life will be good for me and family. I want to learn about people and life in Ireland. I am sure it is a good country.” She nods.

In the following conversation, Deidre learns that Ahmad studied electrical engineering in Aleppo and after fleeing Syria nine years ago, has been working as an electrician in Beirut—so, this is where she is, she notes. He can just about afford to pay the high rent for their room and feed and clothe his family. However, he can’t afford the private school fees for his children, the public schools are full, and the waiting list is very long. His kids haven’t started school yet. He is desperate to get to Ireland so that they can attend school.

She can understand this. “Hopefully, you and all the other Syrian families will come to Ireland and I hope I will be your English teacher,” she says and means it.

She realizes there is a lot to learn about these kind people who have gone through so much trauma. Their wishes are basic; peace and security to provide their children with a perspective for a better life.

Standing up she thanks Ahmad and Amira, saying she has to leave and visit other Syrian families but reiterates that she hopes she will see them in Ireland. She adds how impressed she is with Ahmad’s good English.

She says goodbye to the children, who wave without taking their eyes off the TV.

The couple accompanies her to the doorway and thank her.

Humbled, she wanders off down the corridor reflecting on the extraordinary visit, and with a start realises she doesn’t know how she is going to get back to Ireland.

She takes the bottle out of her pocket, thankful that she brought the bottle and her mobile along with her. She twists off the lid and carefully shakes a few pills onto the palm of her hand.

“I guess it doesn’t matter which colour I choose. They’ll all surely get me home,” she grins.

Without a second thought, she pops a green pill into her mouth and, quickly closing it, puts the bottle back into her pocket just as the trembling begins.

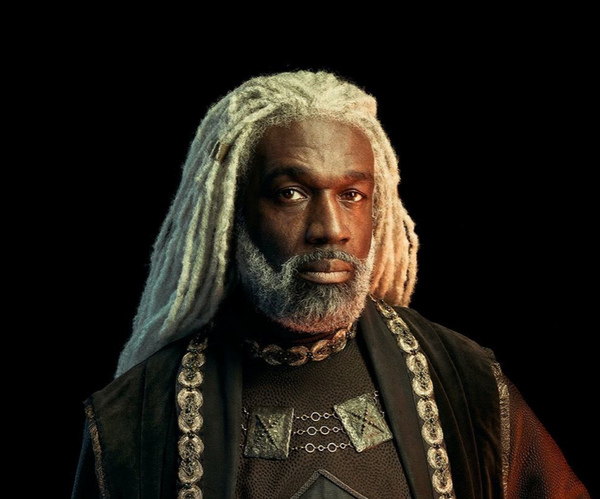

Photo by Terimakasih0 on Pixabay