I've been a statistic all my life, and all my life I've fought to make those statistics null and void in the lives of my children. At an early age, I became three negative statistics, destined for failure:

1. a runaway/homeless foster youth

2. a teenage mom

3. a high school dropout

Society Labels Us

At seventeen, I ran away from my foster group home, became pregnant, and at eighteen married a violent, abusive, predator four years my senior so that my son wouldn’t be a “bastard” to appease religious and non-religious folks alike in the Bible Belt. Little did I know that the marriage saddled me with another negative statistic: my life would be a harrowing uphill climb. Completing high school was no longer an option for me. Because I left state custody, if I re-enrolled in school there was a strong possibility I would be picked up by the South Carolina Department of Social Services, which was a risk I wasn’t willing to take. I became another statistic: an official high school dropout.

When I turned nineteen, I permanently separated from my abusive husband and became a single mom of a six-month-old son with no clue of what to do next. Two years later, I was engaged and gave birth to my second son. Raising two young kids taught me one important lesson:

People my age shouldn’t have kids.

Why? Because it’s a lot of work, and twenty-one-year-old adults aren’t emotionally or financially stable enough to handle the taxing work of raising little people. I knew that my circumstances as a single Black mother made me a statistic, and not in a good way. What I didn’t know was how I would dig myself out of the hole I had gotten myself into, but I knew I had to.

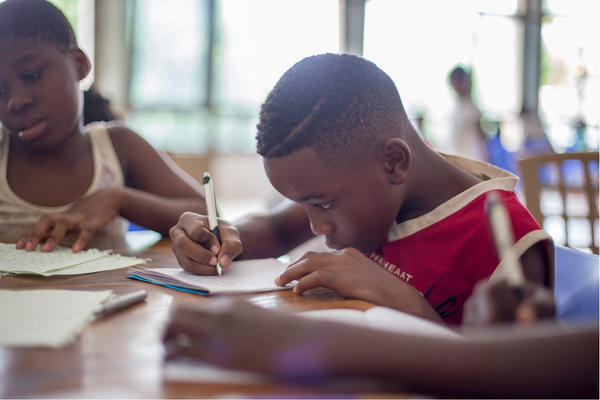

My teachers showed me all the things I could be with a good education. School was my safe-haven before foster care. There I learned how to socialize, read data, draw, perform, and where I developed my ferocious appetite for learning.

Related “Single Parents Are Raising More Than One-Third of U.S. Kids”

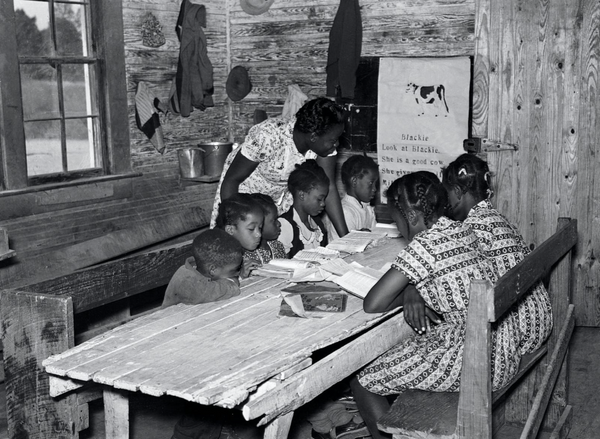

My teachers were from a different era. They showed us they loved us, even when they disciplined us. I can’t recall one incident during my education when I experienced racial bias. My teachers treated me better than my mother did. For all intents and purposes, I received a very good, public education, but I didn’t finish. And what education I did have wasn’t enough to help my children.

The only way I could ensure that my kids would not fall into the same trap as their mother was to ensure they got a good education and by loving them to life. I knew that a good education bettered their chances for better opportunities in life. But I lived in a little backwoods town at the time, and the vast differences between rural public education and urban, or even suburban, education made that a serious challenge.

Education Data Accidentally Labels Us

As my children grew and began their public school education, I learned that my screw-ups and missteps were now negatively impacting them. Public school administrators and educators made many assumptions about me and my kids which made it hard for them to get a fair shake. For instance, when I married, I kept my maiden name. The implications it might have on teachers and school administrators never dawned on me. Being a young, divorced, Black mother with a surname different from that of my child automatically got me labeled as the stereotypic single Black mother with a fresh heaping of all imaginable dishonor.

During PTA meetings and parent/teacher conferences, teachers treated me differently from the married couples and even dads due to my perceived single mom status. Some would talk to me with that sympathetic tone social workers use when helping a troubled family. I resented it immensely. I began to understand how school data was being used to help reinforce labels and stereotypes about my Black children, which impacted how they were treated and educated.

My kids’ school used my income as a single mother to determine whether my boys received free or reduced lunch. They made assumptions about my children based on this. For instance, their teachers assumed that since they were Black boys they would be troublemakers due to an unstable home. Which was not the case. If my sons showed any negative emotion at all, they jumped to the conclusion that they had behavior issues, which they did not. They were often surprised as there weren’t disciplinary issues with my kids. Data collected about my sons’ standardized test scores were used to see if they fit the old stereotypical trope of the young Black male in the single-parent household on his way to being behind and headed to prison.

What schools didn’t know was that education was a priority to me and a non-negotiable in our home. My kids read, watched PBS; we made regular trips to the library; and I signed up for everything that would get books to my home. My kids were smarter than most in our area, and because I hadn’t received a rural public school education, I provided my kids with tools their Black classmates’ parents couldn’t.

Early Experiences In Racialized Education

I wasn’t equipped for the systemic racism that came with educating my sons, nor the history of racial terror tied to my new hometown.

Raising Black children in a place considered the “Cradle and grave of the Confederacy” was a long, hard fight. Dealing with rural public education systems taught me just how race and class factor into people’s perceptions, and how the public education system unknowingly sets up many kids with lots of potential for failure and inequity.

When my oldest son was in the first grade, my first-hand experience with the role racism and classism played in segmenting Black boys in education shook me to my core and changed how I advocated for my sons and others receiving a public education forever.

Demographic data and personal biases played a huge role in how rural kids were grouped. The school kept countless Black children behind. Black children were disciplined differently. There was little tolerance for misbehaving Black youth compared to white students. All the disciplinarians were white men, which made many Black parents uncomfortable. It became evident there were two tracks in the city’s only elementary school for children: the track of success for white kids and the obstacle course for Black kids.

It wasn’t until the end of the school year that I noticed the children in the class were grouped according to where they lived and not by any academic testing rankings. Nearly the entire class was male, predominantly Black, and most of them came from single-parent homes and lived in the same racially mixed, middle-/low-income Black community. After discovering the teacher failed every Black child and recommended they all be retained, I asked the mothers of my son’s classmates if their kids held back. And indeed they were.

I wondered how this white teacher — or any teacher — could flunk an entire class of Black kids and not be held accountable. The teacher seemed to derive great joy from holding our Black sons back, ensuring they would be behind forever. I left the county, and I never looked back. I knew if my sons were going to make it out of school, it would be an uphill battle.

Location, Location, Location

I moved my family to a more affluent neighborhood in a different county and it made all the difference in the world. My boys’ elementary school experience was wonderful. They began to flourish and had more opportunities to learn. The teachers treated my children with respect, encouraged them to be all they could be, and told me how bright they were. My boys took lots of field trips that broadened their horizons. Perceptions of me and my children as inferior dissipated. Finally, I felt that I could entrust my children to the school system.

That was until middle school.

As my sons got older and bigger, perceptions about my race and class because of my surname caused teachers to insinuate negative things about my family once again. My kids told me the things their teachers said that they perceived as racist, which made it harder to keep them motivated. All the teachers I’ve ever had issues with were white, all the complaints came from them, too. It seemed the white teachers relied only on their concepts of what a nuclear family should be, and held a very low tolerance for any deviations from that. When teachers disrespect children they don’t realize they’re only making their jobs that much harder.

When kids don’t feel respected, they check out. Kids will look to other youth who encourage them, even if those youthful influences are negative. I spent a lot of my time licking wounds and cheerleading, but I also spent hours and eventually years discussing race, teaching my sons about the racial history of where we lived and what the implications meant for them. I taught them how to learn from their educators despite their racist behavior.

Since growing up Black would be hard for them, I had to let them know I had their backs. The negative public education experiences and microaggressions by insensitive educators began to take their toll. I spent the next seven years ensuring that my sons knew their rights in public education. The more I learned, advocated, and involved I became, the more push back I received from upper-middle-class white mothers. They expected me to know nothing about education. But because I was a grant writer and federal grant reviewer for the U.S. Department of Education, I was well versed in what public education should be.

More Hurdles to Getting a Good Public Education

Increased parental involvement opened my eyes to my children’s experiences. Living in a small town where whites rule everything makes it difficult for Black children to achieve, and different for parents to engage. The more involved I became in their education, the more I saw how much my presence wasn’t wanted. But I kept pushing back.

I shared with Black parents my findings and got more Black parents involved. The Blacker the PTA became, the more helicopter moms fought and undermined us. While the school administration was happy that Black parents felt more comfortable coming to the school, some parents and teachers wished we would go away.

Some made their feelings known by all piling on negatively when we made suggestions on ways to better engage with Black and Hispanic youth. Others suggested ideas that were not culturally inclusive and sometimes downright racist, which was also a sign to many parents they weren’t respected or wanted. To us, it felt like no matter what we did; they set us up to fail. Keeping our children motivated, determined, and thriving was a challenge throughout high school.

Over the years, I learned my absence and my silence gave consent to the public education system to handle Black children however they wanted to. When we Black parents and caretakers didn’t show up, white teachers, white soccer moms, and professional/politically astute white professionals assumed we Black parents didn’t care. When we showed up, they worked hard to make sure we knew our places, which was always behind them and their kids. But we did not give up.

Ultimately, I learned that in this world for Black children to have a fighting chance at getting a good education and a promising future, parents must take an active role in the process and not assume all teachers are looking out for their kids.

I was glad when it was finally over. My kids made it out alive, but not without scars.

Past Educational Memories Haunt

My son shared with me some things teachers and coaches said about him and me I had never heard before. They broke my heart because he’d been carrying around emotional baggage for nearly eleven years now. I often wonder why some people go into public education if they are prejudiced? I know some people select teaching because it’s a noble profession

We entrust our children with teaching professionals five days a week from eight to nine hours per day, and we want people who will care for our children the same way they would care for their own. If parents and students wanted to be judged we’d go to court. Public education should be strictly about teaching our youth. They deserve to be shaped and molded free of their teachers’ negative stereotypes and that come from data, personal biases, and institutional racial inferiority complexes.

We Made it

We all graduated. My sons, and my stepson all graduated from high school on time. Two of my sons graduated college, on time. Instead of my high school diploma, I earned my GED while my boys were in middle school. And I finished college while my sons were in high school. My children and I started as statistics, but despite unfortunate circumstances, bad choices, all roadblocks in our way, and racist microaggressions, we made it. I refused to allow America to put me down so that someone else could be lifted up. And I would not allow bad educators to undermine my children’s education and future.

Getting a good public education is difficult for many. Children in foster care, children of incarcerated parents, impoverished parents, parents of addicts, parents of children with special needs, Black children and families, immigrants, and Spanish-speaking families often find it challenging to get a fair shake in our public education systems.

Public education has a way of building us up and tearing us down at the same time. Our public education system could be great, but perceptions about our race, stereotypes, and data can prevent it from being so. Public schools save children, but they can destroy them, too.