Yesterday, July 4th, 2025, we celebrated the 249th birthday of the United States. For those of you who have started the countdown, there are only 364 days until we celebrate the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Today, however, is the 173rd anniversary of Frederick Douglass’ famous “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” address.

By examining the two events side by side, we gain insight into the complicated nature of American history. For students and teachers, it provides an excellent opportunity to hold the balance between the great successes of the United States and its often-unmet promises. The Declaration is primarily remembered as a cornerstone document of the founding of the country, and its approval is celebrated as the nation’s birthday. While there is much to praise in the Declaration, it reminds us of the blinders and biases that were prevalent at that time. For example, at no point in the Declaration is there any consideration of the British perspective or why they felt constrained by events to act as they did. Douglass’s speech is a frontal attack on the United States for its hypocrisy but also encouraged the end of slavery and the growth of the country into a more perfect Union.

Before delving more deeply into Douglass’s speech, it is important to review the events that led to the American Revolution and the Declaration of Independence. In the aftermath of the French and Indian War (1754–1763), the victorious British faced several major challenges in their American colonies. First, the British government was now over ₤133 million in debt. Having nearly doubled the debt due to the war, the government quickly introduced new taxes to fund the expanded empire and repay the debt. Second, the British were now in charge of Canada and the Ohio River valley. Facing rebellion at the hands of the Odawa, led by Pontiac, the British issued the Proclamation of 1763, which forbade settler expansion west of the Appalachian Mountains’ ridgeline. Now, in addition to facing higher taxes, the colonists were frustrated by attacks on their economic well-being and violations of their original colonial charters.

The key events from 1763 to 1775 are familiar. The Stamp Act, Townshend Duties, the Boston Massacre, the Boston Tea Party, and the Coercive Acts are all the stuff of school history classes and projects. Yet the causes are more complex. The economic symbiosis between Great Britain and her American colonies remained strong for a long time. The colonies enjoyed an era of salutary neglect as Britain was preoccupied elsewhere. By the time of the American Revolution, the close economic relationship between England and the Colonies had soured. Not only did the debt and subsequent taxes anger the colonists, but their economy had also matured to the point where England’s insistence that the colonists could only import from them and laws against the development of home-grown manufacturing were now hampering its further growth.

In addition to the economic struggles, the colonists’ ideology caused them to view events through a particular lens. The influence of Enlightenment thinkers such as John Locke, coupled with the ideas of the radical Whigs in England, convinced them that liberty was always under assault. Only with the greatest vigilance could tyranny be defeated. Thus, as England tightened their control over the colonies, punished them for resistance, and tried various schemes to increase taxes, American colonists saw a nefarious plot to reduce them to slavery. As John Dickinson emphasized in his Letters from an American Farmer, the danger of low taxes. Since the percentage was minimal, people might accept the taxes and then give up on the idea of “no taxation without representation. The Declaration of Independence was full of charges against the King that reflected the ideological concerns of the Revolutionary leaders.[1]

We remember the Declaration for its lofty ideals and crucial place in the creation of the United States. It contains sublime phrasing as it outlines the natural rights that justify independence.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.

But it also contains some significantly more problematic statements.

“He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.”[2]

Jefferson realized that by declaring independence after the King had sought to establish a large reservation west of the Appalachians, the land would be theirs. The United States built its freedom by displacing Native Americans from their lands and placing them into a state of utter dependence.

Jefferson’s rough draft of the Declaration, which he thought far superior to the final draft, included the following bizarre paragraph.

He has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating it’s most sacred rights of life & liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating & carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere, or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither. this piratical warfare, the opprobrium of infidel powers, is the warfare of the CHRISTIAN king of Great Britain. determined to keep open a market where MEN should be bought & sold, he has prostituted his negative for suppressing every legislative attempt to prohibit or to restrain this execrable commerce: and that this assemblage of horrors might want no fact of distinguished die, he is now exciting those very people to rise in arms among us, and to purchase that liberty of which he has deprived them, & murdering the people upon whom he also obtruded them; thus paying off former crimes committed against the liberties of one people, with crimes which he urges them to commit against the lives of another.[3]

In this paragraph, Jefferson simultaneously blames George III for the slave trade and for not limiting it. Later, he attacks the King for encouraging the enslaved to join the British army in exchange for their freedom. Jefferson refers to slaves as men, even though he makes no efforts to free his slaves, except for those who were his biological children.

So, which is it? Was slavery an evil foisted upon us by Britain, or is the King evil for offering to free slaves? The committee that finalized the Declaration wisely omitted, as it was both self-contradictory and threatened the support of the Southern Colonies for the colonial cause. It does provide insight into the thinking of a man who, forty-four years later, wrote, “But, as it is, we have the wolf by the ear, and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go. Justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other.”[4] Perhaps for Jefferson, both ideas were simultaneously true. The existence of slavery was evil, but it was impossible to extricate oneself from it.

Frederick Douglass fled from slavery to become an extremely influential writer and abolitionist. Paul Hanson, a scholar of religion at Harvard Divinity School, described Douglass, along with Abraham Lincoln, as one of the top two American prophets before the Civil War. As Hanson went on to argue, “The contradictions and ironies that had become lodged in the heart of the nation could not have found a more propitious alignment of time, setting, and mouthpiece than on July 5, 1852 (sic), in Rochester, New York, with Frederick Douglass’s speech ‘What to the Slave is the 4th of July?’”[5] The Rochester Ladies Anti-Slavery Society had invited Douglass to Corinthian Hall, where he delivered a speech that seared into the American psyche.

Douglass gave the speech amidst rising tension about Slavery in the United States. Just two years earlier, Congress enacted the Compromise of 1850. The Compromise admitted California to the Union as a free state, banned the slave trade but not slavery in Washington, DC, and disposed of the remaining bonds from the Republic of Texas. Most significantly, the act created a new and much stronger Fugitive Slave Law, which became increasingly controversial, especially since it called for the deputizing of Northerners. If northerners refused to play the bloodhound, they could be fined $1,000.

I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought life and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth [of] July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty, and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony. Do you mean, citizens, to mock me, by asking me to speak to-day?

At a time like this, scorching irony, not convincing argument, is needed. O! had I the ability, and could I reach the nation’s ear, I would, to-day, pour out a fiery stream of biting ridicule, blasting reproach, withering sarcasm, and stern rebuke. For it is not light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder. We need the storm, the whirlwind, and the earthquake. The feeling of the nation must be quickened; the conscience of the nation must be roused; the propriety of the nation must be startled; the hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed; and its crimes against God and man must be proclaimed and denounced.

What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelly to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciations of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade, and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy — a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages. There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices, more shocking and bloody, than are the people of these United States, at this very hour.[6]

Just two years later, in Framingham, Massachusetts, William Lloyd Garrison stood on stage on the Fourth of July and burned the Fugitive Slave Act. After, to the shock of many in the audience, Garrison burned the Constitution, calling it a compact with hell. Later in the day, Henry David Thoreau, standing on the ashes of the Constitution, delivered his famous Slavery in Massachusetts address. Having just completed his masterwork, Walden, Thoreau was shocked by the recent abduction of escaped slave Anthony Burns on the streets of Boston. Despite a huge outcry in the city, a military escort returned Burns to the South.

Toward the end of his speech Thoreau proclaimed,

I walk toward one of our ponds; but what signifies the beauty of nature when men are base? We walk to lakes to see our serenity reflected in them; when we are not serene, we go not to them. Who can be serene in a country where both the rulers and the ruled are without principle? The remembrance of my country spoils my walk. My thoughts are murder to the State, and involuntarily go to plotting against her.[7]

The country gradually tore itself asunder. Stephen Douglas’s Kansas-Nebraska Act was designed to appease the South and allow for Popular Sovereignty, or the votes of the residents to determine the fate of slavery in the territory. Instead, it sparked an era known as Bleeding Kansas when a small-scale civil war broke out in the territory. On May 21st, 1856, a mob led by Donald J. Jones attacked the free capital at Lawrence. They torched the Free State Hotel and then destroyed the presses and buildings of the Kansas Free State and the Herald of Freedom. In retaliation, John Brown and his sons hacked to death five proslavery activists in the so-called Pottawattamie Massacre. Soon, the violence spread to Washington, DC, as Congressman Preston Brooks attacked Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner with a cane.

The next four years saw little improvement. The Democrat James Buchanan was elected president against the nascent and growing Republican party. Soon, the Supreme Court issued the notorious Dred Scott v. Sanford, which proclaimed that blacks were not citizens and had no rights that needed to be respected by the government or white men. Dred Scott was ultimately overturned in 1868 by the Fourteenth Amendment, which asserted that

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.[8]

Soon, the avalanche of events sparked the Civil War. The 1858 Lincoln-Douglas debates clarified many of the key ideas about the expansion of slavery in the territories. The next year, John Brown led a second attack, this one against the Federal Arsenal in Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Though the attack quickly failed, Brown’s attack terrified Southerners who began to form the base of the Confederate army and convinced them that all Republicans were maniacs waiting for the opportunity to destroy the South. Abraham Lincoln, in his Gettysburg Address, took a major step towards healing the breach.

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. . .

It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us — that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.[9]

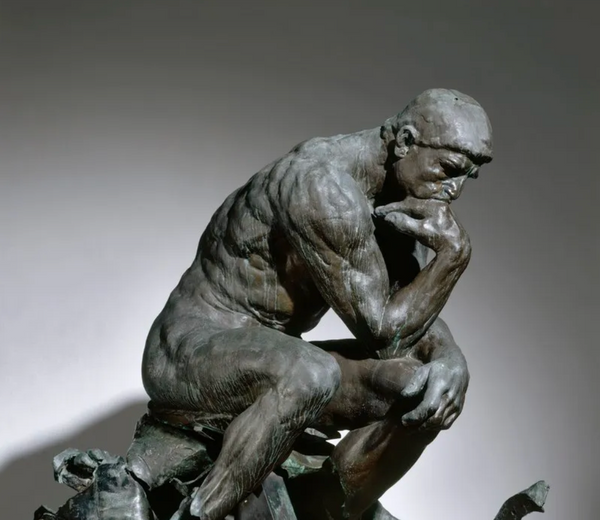

At a time when the country faces polarization not seen since the 1850s, we would be wise to reflect upon the words of Lincoln and Douglass. How might we apply their language in the present?

Are we still committed to the idea that all men, women, and trans people are created equal? What are the key tasks that lie before us as we seek a new birth of freedom for our generation?

What to the undocumented immigrant or the single mother of three who is struggling to care for her children but gets by with the help of food stamps and Medicaid is the Fourth of July? What to trans individuals, who are summarily removed from the military, people who don’t “look American” or are here on visas, who get summarily rounded up and sent to prison camps outside of the US, is the Fourth of July? What to the child dying from AIDS or malnutrition because USAID was shut down, and the elimination of the President’s Emergency Program for AIDS Relief is the Fourth of July? What to Blacks and Latinos who are still behind in economics and education, who are losing Affirmative Action and targeted diversity initiatives, which have given them a leg up into the middle or upper class is the Fourth of July? How would you write sentences about those not currently included in the family of Americans? Who is currently not sharing the blessings and rights promised in the Declaration?

As the influential Civil Rights activist, Fannie Lou Hamer, put it, “Nobody’s free until every body’s free.”[10] Which means that if we ever believe or act like somebody else’s captivity is necessary for our freedom, then we have lost the plot. There are stories from before the Civil War when slaveholders slept in the attic behind a locked door because they were so terrified of their slaves murdering them in the night. Right now, we are so afraid of undocumented immigrants that we are building and celebrating a massive detention system. What else might those centers be used for if there are no more undocumented immigrants to deport? And why does a massive new detention center become the subject of merchandising?

We cannot escape the troubled past of the United States. While there is much to celebrate, there are also darker chapters. They remind us of how far we have come and the difficulty some groups faced in their fight for equality. Every generation must join the struggle, or forward progress will be lost. As Martin Luther King Jr. famously declared in his I Have a Dream speech, “And if America is to be a great nation, [his dream] must become true.”[11]

What are we doing to fulfill the aspirations of the Declaration? How are we listening to Douglass’s prophetic call for justice? How can we cooperate to realize King’s Dream? One idea would be to attend one of over fifty events in Massachusetts where Douglass’s speech will be read. The speeches are sponsored by a grant offered by Mass Humanities.[12] While many of them have already happened this year, events stretch into October. If you don’t live in Massachusetts or there isn’t an event near you, organize one for next year.

Only when we listen, meditate, pray, and have conversations together can we begin to answer these questions.

[1] For readers wishing to delve into the American Revolution in greater detail, consider the following two excellent one-volume accounts: Taylor, Alan. American revolutions: A continental history, 1750–1804. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2016; and Middlekauff, Robert, and Comer Vann Woodward. The Oxford History of the United States. 2, The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution: 1763–1789. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982. For a more bottom-up approach consider Nash, Gary B. The Unknown American Revolution: The Unruly Birth of Democracy and the Struggle to Create America. London: Penguin Books, 2006.

[2] Declaration of Independence: A Transcription,” National Archives and Records Administration, accessed July 4, 2025, https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration-transcript.

[3] Thomas Jefferson, “Declaring Independence: Drafting the Documents Jefferson’s ‘Original Rough Draught’ of The Declaration of Independence,” Library of Congress, July 4, 1995, https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/declara/ruffdrft.html. For individuals who want more information about the development of the Declaration and its impact see, Maier, Pauline. The american scripture: Making the declaration of independence. New York: Vintage, 1999.

[4] Anna Berkes, “Wolf by the Ear (Quotation),” Monticello, accessed July 4, 2025, https://www.monticello.org/research-education/thomas-jefferson-encyclopedia/wolf-ear-quotation/.

[5] Paul D. Hanson, A Political History of the Bible in America (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2015).65.

[6] Frederick Douglass, What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?, accessed July 5, 2025, https://masshumanities.org/files/programs/douglass/speech_abridged_med.pdf.

[7] Henry David Thoreau, “Slavery in Massachusetts,” De Gruyter Brill, May 21, 2013, https://www.degruyterbrill.com/document/doi/10.12987/9780300165623-011/html. For an outstanding summary of the setting, argument, and impact of Thoreau’s speech, see Walls, Laura Dassow. Henry David Thoreau: A Life. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2017. 346–8.

[8] “U.S. Constitution — Fourteenth Amendment | Resources | Constitution Annotated | Congress.Gov | Library of Congress,” Constitution Annotated, accessed July 4, 2025, https://constitution.congress.gov/constitution/amendment-14/.

[9] Abraham Lincoln, “The Gettsyburg Address,” The Gettysburg Address by Abraham Lincoln, accessed July 5, 2025, https://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/speeches/gettysburg.htm.

[10] Keisha N. Blain, “Fannie Lou Hamer’s Message to Contemporary America,” AAIHS, October 7, 2022, https://www.aaihs.org/fannie-lou-hamers-message-to-contemporary-america/.

[11] Martin Luther King, “I Have a Dream Speech,” Avalon Project — I have a dream by Martin Luther King, Jr, August 28, 1963, accessed July 1, 2025, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/mlk01.asp.

[12] MassHumanities, “2025 Reading Frederick Douglass Together Events Announced,” Mass Humanities, June 26, 2025, https://masshumanities.org/2025-frederick-douglass-readings/.

Member discussion