I encountered (yet again) another well-meaning adult white person who commented on America’s love affair with racism — on Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s birthday, no less. After seeing the increasing social and national protests initiated and led by Black Americans demanding to be treated as fully human just like the rest of America and listening to Black people saying “Just see me as human and stop penalizing me for being Black,” this person’s response was “Well, I don’t see color, so I am not responsible for this racism.”

I was taken aback by this frank, open response, but I can fully understand it. I used to say those words, too, when confronted by the presence of people who were not like me. I used the phrase as a way to avoid engaging in the very hard conversations about seeing color and the appropriate way to respond to it. I used the phrase to mean what most white people mean: “I’m not going to acknowledge Black people in my life as Black.”

Denying that Black people are Black is the method we white people in America use to avoid seeing or doing anything about racism. That our fellow human beings are categorized as less-than by those who are dominant in society is neither arguable nor understandable. We must factor in this: In America, we white people have made race one of the most important reasons for shuttling people into the “favored” or “not favored” box. Or “privileged” and “not privileged.” Or “desirable” and “not desirable.” “White” or “Not white.”

By using words to hide reality, white Americans treat the harsh circumstances too often meted out to Black Americans as some mysterious workings of the unseen hand of Adam Smith or Hammurabi or Darwin. For some unfathomable-to-white-people reason, Black Americans simply live more difficult lives from birth. They naturally have a lower rate of survival where they are more likely to be ill from preventable, stress-related diseases. Of course, they live shorter lives compared to others.

“That’s just the way things are.”

Doesn’t it seem odd to you that schools, homes, employment, social advancement, political power — all are somehow less-than for Black Americans than almost any other group? “There’s nothing to see here, folks. Move along.” Some would have you believe that Black Americans just suffer more twists of fate than anyone else, and none of this is due to any actions, policies, or attitudes of white people who coincidentally also pull the levers of power in schools, homes, employment, social advancement, and political power. Surely, all of this is just a series of repeatable, predictable happenstance that disproportionately falls upon the lives and bodies of Black people. Right?

Nothing could be further from the truth.

Along with the oppression experienced by Black Americans is the objective reality that this is indeed being done to them for no other reason than because they are Black people living in a white America. To point this out — that this is all by design and targets Black Americans — is to say that this is entirely wrong, that something must be done about it — and we white people own the work that will bring about change. To quote a sign we’ve seen in stores before: You break it, you bought it. The status of Black Americans in the United States is due to the designs of white people who set up American to benefit white Americans, and to both directly and indirectly exclude, otherize, and oppress Black Americans.

When we as white people say “I don’t see color” we are not saying anything about our visual acuity. I’ve never seen these same people wearing mismatched clothes, for example. I’ve never seen them confused by whether an orange is ripe or unripe. I’ve never seen them stopped at an intersection, confused by lights on the signal ahead. They observe and recognize color. But we say this as white people so that we can avoid culpability and the responsibility we have to do something about it.

It is the reality of America that white people do recognize color, and use it for judgment about a person’s character. Or a judgment about a person’s inclusion into a picture or ability to do the things that white people do freely.

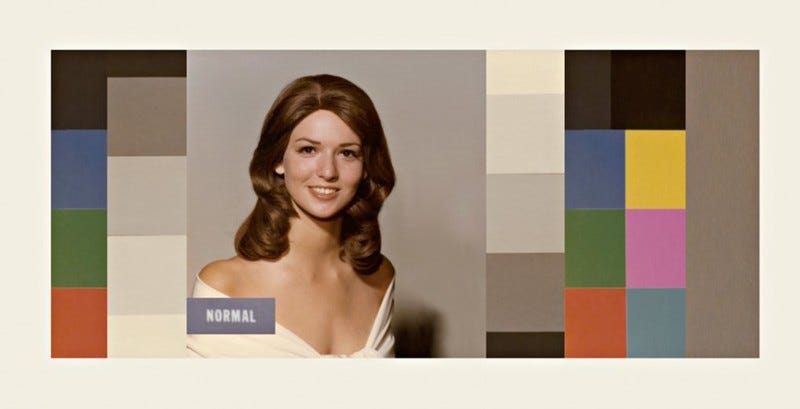

The Shirley Card

In the early days of color photography and film, there were problems with knowing if a particular image was true-to-life in its color representation. The solution was to make a standard card, separate from the camera, that was used to calibrate the colors. The card contained a few reference colors and a picture of a model who showed what the output would look like if a woman were photographed or filmed. The model’s name was “Shirley,” and her face — and skin tone — became the standard for color-correction for several decades. That card was circulated as the “Shirley card.”

But Shirley was white. And that meant that color film was tuned to favor white skin. Back when color film was just coming into use, this wasn’t a problem, because most camera shoots and film productions were comprised of mostly white people.

Black people couldn’t seem to be depicted correctly, however. Photographs and films that included Black people tended to flatten their presence with a smudginess that showed no details, no highlights, no subtle contrasts. But Black people weren’t the focus of American industry, and so it was just an annoyance and nothing more.

What turned the situation from an annoyance to a problem that had to be solved was that other uses for color film couldn’t photograph brown objects correctly as well. Furniture manufacturers could not get their items to show wood grain or even the distinguishing marks of one wood and wood stain over another. Candy makers couldn’t show the difference in colors of their chocolates. Color film at the time simply couldn’t accurately reproduce wood or candy for their advertisements and marketing. And that hurt the bottom line.

So film manufacturers came up with better solutions. Now, newer film can replicate the range of Black skin tones. Better lighting and an understanding of how Black skin handles light differently has brought much better production values when Black actors and models are included. Rather than a mushy general brown color, modern productions use lighting and makeup to better represent the tonal values of Black skin for film. Witness the subtle color techniques used in the film Moonlight for an example of beautiful photography of Black people even under the dim blue light of the moon.

The situation where Black people couldn’t be filmed or photographed correctly came about because the originators of color film simply didn’t pay attention to color in people. They saw the colors of the nature that they wanted to see — the flowers, the sky, the sun, the bright sunny fields. They factored in the variations of hue in their characters and their audiences, who were primarily white or white-consuming. And so film was made to represent whiteness and white values. Not seeing color meant that an inferior product was circulated for decades until enough people who needed a commercial value for full-color film complained enough.

The problem was not solved by Kodak and other film manufacturers saying “Hey, we screwed up by not including Black people in our color range” but by their customers saying “Hey, we’re losing sales of our film to furniture manufacturers and candy makers.” It was the bottom line that brought about change, not an urge for social justice and fairness in representing Black people as people.

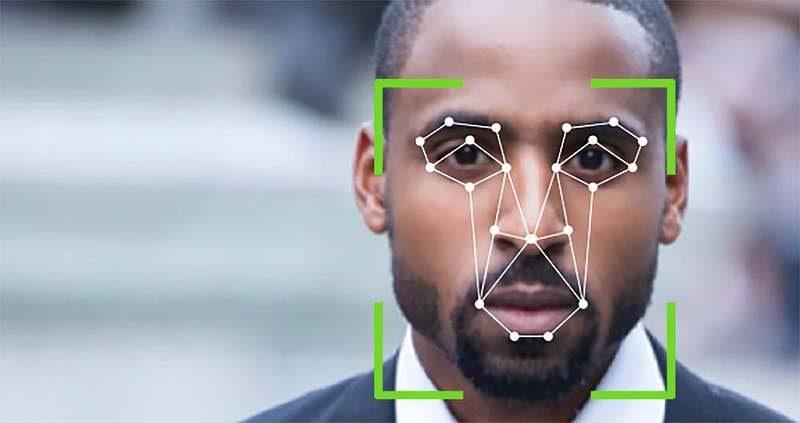

AI and Facial Recognition Software

It’s becoming popular in policing to have cameras everywhere filming everything. London, England, is an outstanding example of a city with cameras watching the populace from nearly every vantage point: you have privacy only in the loo, it seems, but even then, who knows?

The cameras themselves only record the people. Finding miscreants after-the-fact means that other people must laboriously review every second of film.

Enter artificial intelligence, or AI, and facial recognition technology. AI can be used to spot problems while they happen and report on the perpetrators by seeing faces and then comparing the filmed face with a face on file. We might not appreciate the complexity of this accomplishment, but AI identifies not only the face in a picture, but the distinguishing features that can tag one person versus another as the party of interest.

But it turns out that this AI often confuses one Black person for another. And when it confuses people and labels them as suspects, then the criminal justice system kicks in, and innocent Black men are arrested and jailed for crimes they had no part in. These Black men are incorrectly identified by white-created, white-programmed, and white-optimized facial recognition software. The reasons are not hard to figure out: the database of images used to train the AI to recognize a face includes a population of faces that comprise more white people than others. It is not the fault of the AI in that the AI was given limited information. It’s a correctable problem, but it’s still a problem.

So why did this problem occur, that Black people were misidentified? In part, because the people who made the AI, who developed the training, who used the database of mostly white people were largely ignorant of what they were seeing. White faces were expected, and there weren’t enough people asking “does this technology work on all skin tones?”

This was exposed earlier in other circumstances, where automated soap dispensers could not recognize black skin tones and thus would not work for Black people. But the problem wasn’t corrected until Black people who were falsely arrested began to file lawsuits that cost police jurisdictions and cities lots of money. Arresting the wrong people wasn’t the concern. Paying the money was.

The common thread here is that until we acknowledge something as it really is, we won’t be able to effect change. We can’t manufacture a film capable of capturing the rich complexities of skin tones until we are honest that we aren’t accounting for the varieties of skin tones. We can’t create a technology for identifying human faces correctly until we recognize that humans come in a variety of colors.

When we say “I don’t see color” when talking about Black people — especially when we say it to Black people — we do an incredible disservice to their existence and their reality. We are attempting to erase their very presence in our lives and communities and workplaces and schools and religious services and our nation itself. We are placing our very foolish desire to maintain deniable innocence as a priority over the very real need for accountability and truth-seeking. And to be both blunt and honest, we are telling our friends and loved ones that they simply do not matter to us because we refuse to see them in all that they are.

We won’t be able to fix a society that stratifies privilege and grants access based upon race until we admit that this is the way things are. And not only see those practices as wrong but as something that must be changed today.

Seeing color involves thinking about the actual situations Black, Indigenous, and People of Color face in America today. It means doing the hard work required to better understand the experience and cultures of People of Color. Doing so, we not only see the people who are suffering, but we see it is because of the systems and behaviors that make their lived experience far more challenging than they should be, and we are then drawn to empathize and act to help make their lives richer.

We cannot bring about justice and truth and connection between white people and Black people here in America until we do the same thing about our own condition. We white people must see color and culture, and embrace the differences, and believe in the inherent value of Black lives. Only then can we get to the place where we have Black lives equally as valued as the lives of others; only then can we say that Black lives matter.